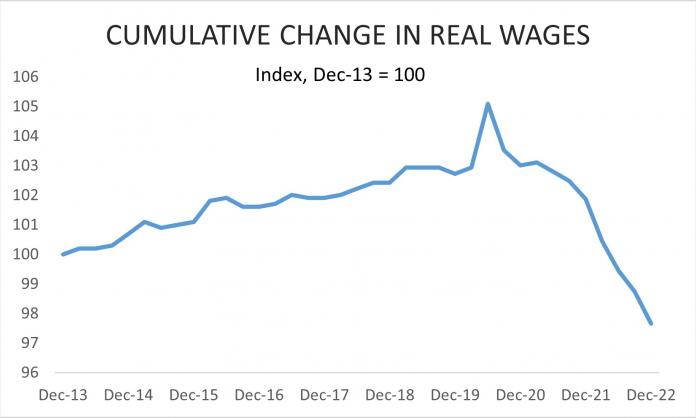

It just keeps getting worse. Real wages are down more than 7 percent from a peak in the June quarter of 2020. The rate of consumer price inflation is falling and the pace of wage increases is climbing, but a gap between the two remains. Real wages cumulatively could be down by 9 percent or more by the end of the year.

This “average” drop doesn’t catch the worst of it. People at the bottom of the income scale are being hit harder. Over the last year, the Bureau of Statistics reported inflation of 7 percent. But prices of essential items that poorer households spend a disproportionate share of their income on were increasing much faster.

Cereal products, for example (rice, oats, bread, breakfast cereals and so on) were up nearly 12 percent. Dairy foods such as milk, butter and cheese were up nearly 15 percent. Other packaged foods, such as the dry-good staples of supermarket shelves, were up more than 11 percent. Electricity was up 15.5 percent. Gas and other household fuels were up more than 26 percent.

It’s going to be a shit winter for millions of people. But this still isn’t the worst of it.

The housing crisis is becoming immense. The latest Domain rental report estimates that capital city unit rent asking prices surged 10 percent in the last three months and more than 22 percent in a year. House asking rents are up 13 percent in a year and by almost one-third in three years.

Again, this is hitting people at the bottom the hardest: the Reserve Bank estimates that more than 70 percent of the poorest 2.2 million households are private renters. Many people now spend more than a third of their incomes on rent alone. Some are spending 50 percent or more.

“It’s not just the people that are on Centrelink benefits. It’s also the people that ... have jobs, have families, that are on a low income, that still can’t afford a private rental”, Meg Hamilton from Melbourne City Mission told the Guardian recently. “It’s a real nightmare situation.”

Then there are the fixed-rate home loans issued during the first two years of the pandemic, which are jumping to much higher variable rates. The average mortgagee is about to be charged an extra $200 per week in repayments. That’s the “mortgage cliff” we’ve been hearing about. It began this month and will stretch past Christmas as more than 1 million borrowers fall—or are pushed—onto much harder times.

Of those on variable rates, the Reserve Bank believes that up to 15 percent will this year reach “negative spare cash flow”—that is, their mortgage payments and essential living expenses will be greater than their disposable income.

Yet just as peak financial pain looms for Australia’s working class, federal Treasurer Jim Chalmers will reportedly abolish the low- and middle-income tax offset in the 9 May federal budget. That will give more than 10 million mainly working-class people “one of the largest tax increases in history”, according to Shane Wright, senior economics correspondent for the Age and the Sydney Morning Herald.

“A person earning $50,000 a year will suffer a 3.4 per cent or $29 a week cut in their after-tax income when the offset ends while someone on the average wage of $90,000 will take a 2.1 per cent hit”, Wright calculates.

So as the capitalists drive down real wages by up to 10 percent (who knows when it will end?), the Labor government is going to drive down working-class incomes by another 2 to 4 percent.

The upcoming budget will no doubt include a few headline-grabbing measures to “ease cost-of-living pressures”—expanded eligibility for the parenting payment perhaps, a small increase to the dole if the unemployed are lucky.

Mostly they will be akin to putting fancy curtains on a falling-down house.