The biggest winners in federal budget week were investors in mining giants BHP, Rio Tinto and Fortescue Metals. The record iron ore price of well over $200 per tonne had financial analysts estimating $65 billion in dividend payments to share owners this year, most of them overseas institutional investors.

These super-profits on sovereign resources, which successive governments, both Labor and Liberal, have refused to tax properly, put into the shade the so-called spending spree of the federal government. The outlay of an extra $24 billion per year is bizarrely being described in the media as somehow revolutionary—even when almost one-quarter of that “spending” is revenue forgone in business tax deductions and write-offs, making business owners the second big winners of budget week.

Others who continue to be recipients of government grace are those with housing investments and large amounts of financial wealth—by and large the top 20 percent of the population, who receive, according to new modelling from the Centre for Social Research and Methods, the lion’s share of the $60 billion per year windfall tax concessions from negative gearing, superannuation tax concessions, the capital gains tax discount and refunds from excess franking credits.

There’s almost nothing for the 116,000 homeless and the millions suffering mortgage and rental stress. And the government says prudence won’t allow it to lift the below poverty level unemployment entitlements by more than the already announced $25 a week. What bullshit.

The aged care sector, which will get an extra $4.5 billion per year over the next four years, is said to be a big budget winner. After the unbearable horror stories coming out of the royal commission, any extra money is welcome. But as Gerard Hayes, national president of the Health Services Union, commented, $10 billion had already been ripped out of the sector since the Liberals were elected in 2013. On top of that, he noted, “there is no commitment to permanent, better paid jobs”. No wonder the sector has trouble attracting workers.

The government—and pretty much everyone in the media—says that low- and middle-income earners are big winners because the tax offset measure introduced last year is being extended. That provides an end of year rebate of between $255 and $1,080. But the Treasury forecasts that consumer price inflation will outstrip wage rises, resulting in a 2.25 percent real pay cut for workers this year and a further 0.25 percent next year. The tax cut will make up for that zero percent of the time.

The greatest and most urgent challenge, climate change, received almost no attention in the budget. Nor did quarantine facilities. More than a year into a pandemic that has killed more than 3 million people, and the federal government has done next to nothing on this urgent front. But it made more than half a billion dollars available for its ongoing refugee detention regime at Christmas Island and for expanded mainland detention centres.

There’s always money for the largest democratic rights breacher in the country, ASIO, which gets a boost of $100 million a year. And the military, under last year’s Defence Strategic Update and Force Structure Plan, will receive $575 billion over the decade to 2029-30. As has become the norm in the 21st century, in the choice between bread and guns, guns win.

Mainly because of the projected increase in net government debt to nearly $1 trillion by 2025 and the elevation of federal spending to more than 27 percent of GDP, which will contribute to half of all economic growth next year, Australian Financial Review economics editor John Kehoe calls the budget “a revolution in macroeconomic policy management”.

It’s a revolution only if the frame through which you view macroeconomics is so narrow that a slight swing from one branch of the state (the Reserve Bank) to another (the Treasury) as a stimulator of growth has you wetting your pants.

If you work a regular job, this is not your revolution. So don’t get caught up in all this hype about a new order. Pragmatic shifts in recent years likewise created a big song but were of little substance. The progressive advocacy group GetUp!, for example, heralded a “seismic shift” after the 2017 federal budget, with “both sides of politics ... prioritising bold, progressive economic reform measures”.

That was after the federal government made a distinction between “good debt” and “bad debt”—that used to finance capital assets versus that used to fund recurrent expenditure. The rationale for the distinction was to separate debt that pays for itself by stimulating sustained economic growth and debt that is used to cover immediate expenses.

The shift was a cover for the government’s inability to run a surplus despite promising one forever. The growth of debt during the pandemic, while more significant in scale, is arguably less significant ideologically than the shift four years ago. Running deficits to stimulate growth and charge out of recession is standard practice. It’s exactly what treasurers John Howard and Paul Keating did in the early 1980s and what the ALP did coming out of the 1991 recession. The volume of stimulus has shocked this time around. But then again, so did the scale of the economic contraction in the middle of 2020.

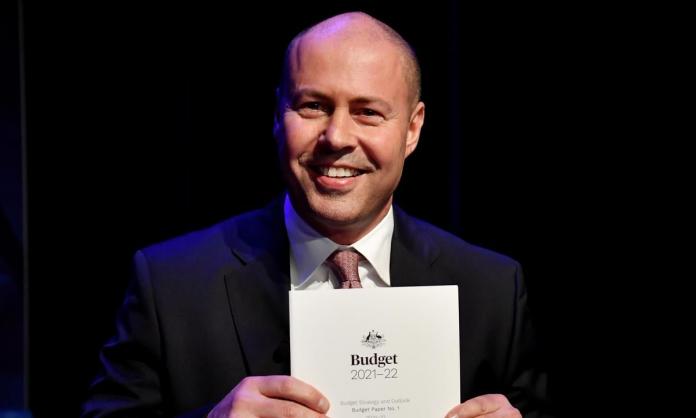

Neoliberalism, the most abused term in economics and politics, must have been reported dead three times in the last thirteen years. But if it has died yet again, no-one told Josh Frydenberg. For him, the markets—those fragile institutions nurtured by capitalist states to allocate resources—reign supreme and continue to be used as the prime drivers, and discipliners, of human behaviour.

Again, if you work a regular job, neoliberalism’s alleged death will also pass you by. Housing policy remains a mass of tax breaks for investors, individual incentives for deposit savers and subsidies for owner-occupiers. And the big four banks—the leeches profiting the most from everyone else’s debt bondage—are reporting super profits again.

The unemployed remain locked in a labyrinth of obligations to private providers growing fat both from job seekers’ misfortunes and from their eventual placement in work—if they are lucky enough to find a job. The NDIS for most people similarly is a giant marketplace of scarcity.

Aged care, despite the squalor, will not be run for human need, the for-profit centres that oversee the death and malnutrition continuing with more government subsidies. Superannuation concessions now cost more than the aged pension, but that private financial behemoth rolls on as the government’s favoured option for retirees because it rewards people with higher incomes.

Pressure remains on the universities to be profit-making institutions. Financial deregulation continues, overseas financial service providers from certain jurisdictions getting the green light to operate here without a licence. Pharmaceuticals and medical research “monetisation” will be incentivised by a little more than half the current company tax rate, rather than the government just directly investing in needed areas—such as vaccine development.

And the $130 billion “phase three” tax cuts, which benefit only individuals earning more than $120,000 a year, are still in the wings. Plus the company tax rate continues to fall.

Budgets are always passed with bells and whistles sounding, governments insisting that workers are the real winners when mostly it’s more of the same gravy train for businesses and the rich. This year is little different. It’s not a revolution. It’s capitalism. It doesn’t change much.