“No force can shake the status of this great nation”, declared Chinese President Xi Jinping. Alongside thousands of People’s Liberation Army soldiers marching through Tiananmen Square in Beijing, a military parade showcased the country’s latest high-tech hardware, including intercontinental nuclear missiles and supersonic drones. It was 1 October 2019, and Xi was opening the celebrations marking 70 years since the founding of the People’s Republic of China. Nearly 2,000 kilometres away, police were suppressing pro-democracy activists in Hong Kong, deploying live rounds for the first time since mass protests broke out earlier that year.

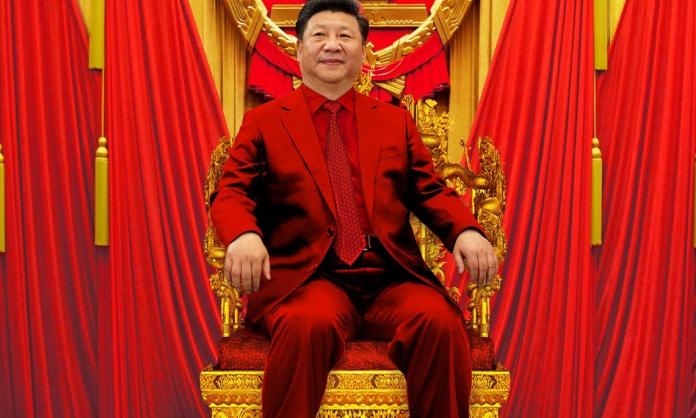

When Xi Jinping became general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party in 2012, and president of the country in 2013, many believed he would continue down the path of his predecessors. But that October day illustrates the Communist Party’s determination under Xi to win a race against time, eliminating domestic and global challenges that threaten China’s rise and the party’s rule. “Xi sees a narrow window of ten to 15 years during which Beijing can take advantage of a set of important technological and geopolitical transformations”, Jude Blanchett writes in a 22 June Foreign Affairs piece. “Strong demographic headwinds, a structural economic slowdown, rapid advances in digital technologies, and a perceived shift in the global balance of power away from the United States demand a bold set of immediate responses.”

As the US strains to halt China’s rise, much attention is paid to the international dimension of Xi’s plan: the high-tech arms race, naval excursions in the South China Sea, vaccine diplomacy, the Belt and Road project, the “unswerving historical task” of integrating Taiwan. Imperial rivalry casts a long shadow over every aspect of policy in both the US and China.

But China is not monolithic: it is internally riven with social tensions, economic fault lines and political vulnerabilities. The breakneck speed of development in the 2000s masked many problems and intensified others. Rebellions in Tibet in 2008, Xinjiang in 2009 and Inner Mongolia in 2011 revealed vulnerabilities in the Communist Party’s rule of the country’s semi-autonomous regions. In 2012 protests against new toxic chemical plants, thousands stormed government offices in China’s south-west, east coast and north-east, halting the projects. A manufacturing strike wave in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis—kicked off by the Nanhai Honda strike in 2010—resulted in the number of strikes doubling year on year until 2015, according to the China Labour Bulletin.

Now that the pace of economic growth is slowing, the problems are emerging. Without a plan to overcome them, the Communist Party’s geopolitical ambitions could unravel. So understanding Xi’s domestic strategy is crucial: Chinese capitalism must remain firmly under the Communist Party’s unquestionable leadership, and the party under his own.

The opening act was Xi’s anti-corruption crackdown. With an estimated 1.5 million party members punished since 2012 for graft, indolence and dissent, it is the largest party purge since the Cultural Revolution. The Central Commission for Discipline Inspection has unlimited powers to investigate all party members, from senior-ranking “tigers” to low-level “flies”. The commission is “an eye that can see thousands of miles and an ear that hears everything the wind blows its way”, the party warned in its official newspaper, the People’s Daily.

The purge has enabled Xi to take down his factional rivals. The public trial and imprisonment of popular up-and-comer Bo Xilai in 2012-13 was the scandal of a generation. It was quickly followed by a life sentence for secret police chief Zhou Yongkang, the first member of the Politburo Standing Committee to be jailed since the fall of the Gang of Four in the late 1970s.

Any disagreements within the party are viewed by Xi as an opportunity for opponents to pry open the party’s dictatorship. Obsessed with the fall of the Soviet Union, the general secretary is determined to avoid the same fate. According to Richard McGregor in his book Xi Jinping: The Backlash, which deals in detail with the anti-corruption campaign, Xi believes that the party must study this era as it enters a difficult new period. “Xi was horrified at how the party had almost evaporated overnight in the Soviet Union”, McGregor writes, quoting Xi as saying: “A big party was gone just like that. Proportionally, the Soviet Communist Party had more members than [the Chinese party], but nobody was man enough to stand up and resist”.

The crackdown has gone well beyond faction fighting. In one of Karl Marx’s early writings, he described the nature of the bureaucracy underneath its self-image as a disinterested servant of the nation. “As far as the individual bureaucrat is concerned, the state becomes his private end: a pursuit of higher posts, the building of a career”, he wrote in his 1843 Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right. The golden age of Xi’s predecessors—when annual economic growth was as high as 14 percent—took this to its extremes. State officials used their political monopoly to scoop bathtubs of cream from the pool of riches generated by foreign investment in the party-facilitated exploitation of hundreds of millions of workers. In an article for Foreign Affairs, Yuen Yuen Ang paints a picture of the bribery that soared after 2000:

“A former minister of railways was charged with taking $140 million in bribes, not including the more than 350 apartments he had been given. The head of one state-owned lender allegedly kept a harem with over 100 mistresses and was arrested with three tons of cash hidden in his home. A police chief in Chongqing amassed a private museum collection that included precious works of art and fossilized dinosaur eggs.”

Xi has no in-principle objection to graft—his own family’s wealth stands at well over US$1 billion. It is precisely to protect the enormous privileges of the bureaucracy in the long term that he must be seen to address it. The gilded age has produced deep resentment among the population. Corrupt officials and income inequality are cited by Chinese people as the country’s two biggest problems, according to a comprehensive survey conducted by Pew Research Center in 2016. The crusade against conspicuous consumption is popular in society, even if, as McGregor argues, it has also left behind “a bucketload of bitter enemies itching for revenge”.

The incestuous relationship between local government and business has led to all sorts of genetic defects in the economy. The path of greatest enrichment—leasing land and borrowing money—was key to China’s enormous expansion. For a decade, real estate construction and infrastructure projects led to a virtuous economic cycle that also made government officials and private investors (often the same person) fabulously wealthy. But it has led to eye-watering levels of debt that the central government must absorb. Funds are drawn away from industrial investment and into speculation. China’s property market is now “the world’s largest asset bubble” at US$52 trillion, according to the Wall Street Journal. It cannot pop or even deflate without ruining the savings of tens of millions of middle-class people and urban workers.

“Access money”, as Ang calls the riches accrued from political favours, pulled the system of local government into the anarchic logic of the market. Officials compete for contracts and spend big on infrastructure, because gaining promotions to higher posts—and getting access to bigger bribes or business opportunities—is dependent on officials overseeing faster economic growth. As long as this stimulated growth in China’s economy, it continued. But as it went on, the party undermined its rule over both the bureaucracy and business. The outcome was a bottom-heavy bureaucracy less loyal to the party and less capable of acting in a disciplined way for the good of Chinese capitalism.

When Xi became general secretary, he was alarmed by this administrative decentralisation and its political ramifications. “Officials in the military, key government ministries, and state-owned enterprises are taking advantage of a weakened leadership at the top of the Communist Party to assert their interests in ways that would have been unthinkable even a decade ago”, John Pomfret, the Washington Post’s bureau chief in Beijing, wrote in 2010. The Politburo Standing Committee now hope a firmer chain of command will bring local governments into line. Aside from the crackdown, they have intensified performance measures for local officials, brought the provincial governors under closer scrutiny and absorbed the 1.5 million-strong paramilitary police force into the command structure of the Central Military Commission, of which Xi is chair.

The party under Xi is also placing greater stress on ideological conformity. “Xi Jinping Thought” was slotted into the constitution of the People’s Republic in 2018—by the same National People’s Congress that removed presidential term limits—and members are mandated to attend party groups dedicated to studying the president’s speeches and policies. After decades of party consensus that Mao Zedong’s autocracy and cult of personality threatened the collapse of Communist Party rule, Xi is rehabilitating the Chairman to legitimise his own personalised dictatorship. Even mild criticisms of Mao’s policies are being scrubbed from school textbooks as examples of “historical nihilism”, a criminal offence since 2018. Marx’s 1843 description again comes to mind: “The bureaucrats are the Jesuits and theologians of the state. The deification of authority is its mentality ... passive obedience, trust in authority, ossified and formalistic behaviour, fixed principles, conceptions, and traditions”.

But Western commentators—often hysterical anti-communists—confuse this “red” style with substance. Orthodoxy is the mark of loyalty in the party, but in broader society, nationalism is an all-China blend of Mao Zedong, Confucius and Jackie Chan. Xi’s “China Dream”—the branding he’s given to the party’s ambitions—celebrates the Communist Party’s role in reviving a glorious 5,000-year-old civilisation from a century of humiliation by arrogant foreign powers.

Patriotism, designed to distract from the inequalities and injustices of Chinese capitalism, is fostered at least as much through mass consumer culture as through the party pulpit. Films glorifying Communist Party history—such as Youth (2017), the Eight Hundred (2019) and Nineteen Twenty-One (2021)—feature all-star casts of China’s A-list celebrities, with special effects budgets and box office records that rival or trump Hollywood. Ticket sales aren’t the only figures the Communist Party can point to for popular support. While deaths from COVID-19 in the US topped 600,000 by July, China has reported fewer than 5,000.

To build support for Chinese imperialism, national pride has also become more aggressive. The ruling class is extremely vocal about the need to “restore” China’s territorial unity, from Xinjiang to Hong Kong, and especially to Taiwan. “Wolf Warrior” diplomacy encourages a popular chest-beating about Chinese supremacy with all the flavour of “USA, USA!” and “Love it or leave it!” more than “Uphold Marxism-Leninism-Mao-Zedong-Thought”. When Global Times editor-in-chief Hu Xijin urged Chinese officials to take the moral high ground instead of mocking India for its COVID-19 crisis, patriotic citizens flocked to social media to brand him a traitor.

Xi came to power promising to give markets the “decisive role” in the economy. Then came 2015. The Shanghai stock exchange experienced a massive meltdown and the collapsing value of the renminbi, China’s currency, led to capital flight. As Lingling Wei reflects in a December 2020 piece for the Wall Street Journal, the tune changed entirely in Beijing: “Markets and private entrepreneurs, while important to China’s rise, are unpredictable and not to be fully trusted”. A month later, top economic adviser Liu He, a market-reform advocate, was insisting that “state-owned enterprises must become the competitive core of the market”.

“The government is installing more Communist Party officials inside private firms, starving some of credit and demanding executives tailor their businesses to achieve state goals”, Wei writes. China’s largest ride-share application, Didi, has been pulled from app stores across the country, its data-harvesting considered at risk of breach by foreign shareholders, and a challenge to party dominance. “No internet giant is allowed to become a super data base that has more personal data about the Chinese people than the country does”, the Global Times editors wrote on 5 July. Or take the sorry tale of Jack Ma, the third richest man in China. His financial technology company Ant Group was set to be floated on the Shanghai and Hong Kong stock exchanges with the largest initial funds ever raised. Following a speech in October 2020, in which he made the bold claim that “success does not come from [Xi] alone”, Ma was hauled into a private meeting with the president. Days out from going public, the project was canned.

However, if state capitalism conjures up images of the markets crushed under foot and steel output planned to the ton, think again. China’s sluggish state-owned enterprises need a shake-up so assets can be freed for the party’s plan to build a domestic high-tech economy. With a firm grip over the private sector, the party can drip-feed market discipline to its state-owned enterprises. Shock treatment isn’t off the table, either: just look at the recent default of debt-laden Yongcheng Coal and Electricity Holding Group, once the most profitable coal mine in the country. As profit margins narrowed, Yongcheng propped itself up via government financing vehicles that got around the central government’s ban on local budget deficits. Now it’s bankrupt. “The episode has obliterated longstanding investor assumptions that authorities will always bail out state-owned enterprises in China”, Sun Yu wrote in the Financial Times in December.

It’s a risky move as China tries to attract foreign investment into its bond markets. But given that US sanctions on semiconductors have undermined China’s national champion Huawei, the party is willing to take carefully managed risks to drive China up the global value chain and reduce its dependence on imported technologies. China might be on the cutting edge of artificial intelligence and quantum computing, but these technologies will go hungry without chips. Funnelling resources into research and development for a high-tech, consumption-based economy—called “dual circulation” in the fourteenth five-year plan unveiled last October—will require ever greater centralisation of party power. “It is getting harder to distinguish between the state and private sectors”, the Economist noted in August last year. “All companies, whoever owns them, exist for the glory of China.”

However, the thought of working-class and democratic revolts is what really keeps the dictatorship up at night. Since 2015, there has been a marked increase in repression. The arrest of 47 Hong Kong lawmakers and activists on sedition charges in February, as well as the raid on and shutdown of Hong Kong’s largest tabloid newspaper, Apple News, on 24 June, mark the end of the Hong Kong democracy movement for the foreseeable future. And in Xinjiang, private and state capital face no fraternal conflict, only mutual interest. “A government-led labour transfer scheme has forced prisoners from ... re-education prison camps into the factories of HP [a US multinational]”, Xqsu writes in an article for left-wing website Lausan. “The carceral continuum between labour camps and supply chain capitalism is plain for all to see.”

The same for the threat of an emerging workers’ movement. The explosive strike wave in mostly foreign-owned factories from 2010 to 2015 was stoppered by a wave of arrests of labour leaders and activists, and organisations like the Panyu Migrant Workers’ Centre were permanently shut. More recently, Chen Guojiang, who organised a mutual aid and collective action online network for China’s 7 million food delivery workers, has been arrested and faces five years in prison. But the working-class struggle cannot be destroyed so easily. Even the Communist Party, which claims to make profits in Marx’s name, cannot get around his insight that capitalism, “above all, creates its own gravediggers”.

In the wake of unprecedented nationwide strikes of tower crane operators in May 2018, labour scholar Wang Jiangsong argued that the crackdown did not and could not suppress the strike wave for good. “The level of consciousness and organizational capacity of workers in China has reached a new level, at least in some sectors and regions, and they’re capable of their own collective action”, he wrote at workers’ advocacy blog China Change.

Even China’s better-educated young people are increasingly feeling the squeeze. Online forums and social media networks reportedly are awash with bitterness about wealth inequality, rising cost of living and intense competition for jobs. The number “996” refers to the gruelling working week expected of employees in the country’s tech giants. “The rich and the authorities monopolise most of the resources, and more and more working class like us have to work from 9am to 9pm, six days a week”, tech worker Elaine Tang told the South China Morning Post in June. “In recent years, property prices have skyrocketed, and the gap between social classes has become wider and wider.”

But another gap—that between urban workers and poorer workers who migrate from the countryside—is narrowing. While migrant workers have moved from southern manufacturing to service industries all over the country, 996 drives young white-collar workers to Foxconn-style suicide, including a high-profile death of an employee at Pinduoduo, an online grocery store. Under the shadow of slowing wage growth and state repression, working-class experience converges on a grey and hopeless vision of the future—unless they fight back.

Will Xi succeed in suppressing dissent and transforming the domestic economy? Only a fool would predict with certainty. US efforts to contain China, and China’s determination to break through, are threatening to spill over into the biggest military confrontation since World War Two. Each imperialist power is working hard to get its house in order. Yet inside each “house” lives, not a family, but an exploiting and an exploited class.