At Canberra Hospital, I am undergoing a well-established treatment for the bone marrow cancer Multiple Myeloma. Like other public hospitals in Australia, Canberra Hospital is staffed by workers who are, in general, very dedicated and very exploited (therefore alienated). They endure low pay, crap shifts, inadequate working conditions and lack of collective control over what they do.

There aren’t enough beds. There aren’t enough staff. Some staff would be more effective with more paid training. It is, like other large workplaces, an authoritarian, top-down bureaucracy, in which arse-covering is an important criterion in the decision-making process. There isn’t enough money.

Very early on Friday morning, in my high care room, it occurred to me that some of the problems in my treatment may not have happened if I’d been on a clinical trial. Clinical trials are an important part of improving the treatment of illnesses. Good trials study the effects, on large numbers of volunteer patients, of a new procedure compared to established ones. They are mainly funded by governments, medical corporations and charities.

For a period, participating in a trial was an option. Both knowledgeable friends and my doctors pointed out the advantages: you are contributing to the advancement of medical science, which would help others, and much more attention is paid to you. You’re special, not just an ordinary patient, subject to closer observation (in effect you experience a higher staff to patient ratio) and the details of the treatment are subject to even more rigorous guidelines (“protocols”) than usual.

I decided to delay treatment – still, I think, a good decision – and the clinical trial closed.

The cancer advanced and it was then time to do more about it. After months of first one then another chemotherapy regime, I was ready for an autologous (self) blood stem cell transplant. The treatment was not physically or mentally pleasant for me and it has also stressed people I love and care about.

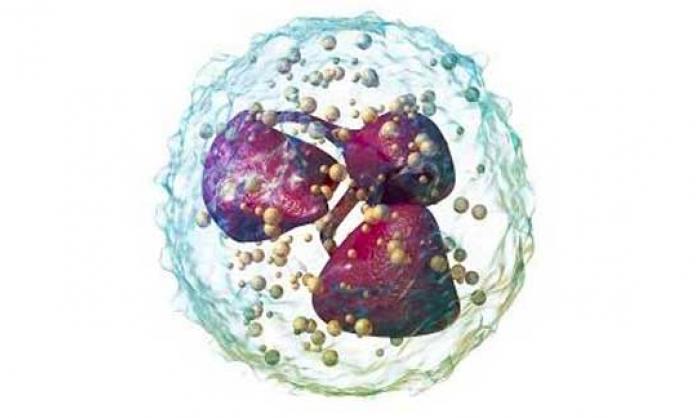

Following the chemo, millions of my own blood stem cells were filtered out through an impressive machine – essentially a very sophisticated little centrifuge – under the supervision of highly trained and competent workers. A few weeks later, I was ready to have half of these put back. That would happen the day after a dose of very poisonous chemotherapy designed to kill off the cancer cells, which would also totally knock out my bone marrow and therefore my capacity to make new blood cells and rejuvenate my immune system.

Slipped into my blood stream again, the previously harvested stem cells would rebuild my bone marrow. The process of the old bone marrow dying and the new being rebuilt takes weeks and you are pretty crook while it’s happening. The goal: to set the cancer back and give me more years of more comfortable life.

But there was a delay between the stem cell harvest and the chemo poisoning and “reinfusion”. A chest x-ray, one of the tests the day before the chemo, showed something. I was put on two additional antibiotics and, eventually a maintenance dose of the drug that had been most effective in reducing the cancer during the second chemotherapy regime. You may have heard of it: Thalidomide.

Used to treat pregnant women with nausea in the 1950s and 1960s, it was a total disaster that caused severe birth defects. But it can be an effective treatment for Myeloma. There are still side effects. Thalidomide can lead to tiredness, lack of mental sharpness and “peripheral neuropathy”: progressive loss of feeling in fingers, hands, toes and feet. At least some of that loss can be permanent. I experienced these side-effects both during the earlier and the Thalidomide chemo regime and then while on a lower dose of Thalidomide, as the x-ray worry was sorted out.

Initially, I was pretty depressed about the delay, having prepared for the heavy stuff of the poison chemo and transplant. But I got on with an editing and then a writing task as diversions.

After more than a week, it turned out that what the x-ray (and a CT scan and another x-ray) found was not a matter of concern. The transplant had to be rescheduled. And more time passed.

“Well”, you might say, “Easter intervened, the doctors involved are all highly qualified, busy people, not to mention the specialised nursing staff, and beds are expensive. And do you expect special treatment Rick, you selfish prick?” All true (apart from expecting special attention). But would this delay have occurred if I was on a clinical trial, meaning that extra money had been invested in my treatment? Probably.

The fundamental issue isn’t clinical trials. The length of the delay was conditioned by the state of hospital funding and staffing and ultimately the priority that the state, territory and Australian governments give to health – as opposed to locking up refugees, funding prisons, policing and the military, handing out special grants for people who argue that climate change is not a big deal. Then there’s the priority of ensuring that healthy profits can be made by business and not upsetting the wealthy or corporations by taxing them too much or, in some cases, at all.

Another experience raised the same issue.

After the poison chemo and reinfusion I stayed at home, under the amazing care of my partner, and visited the haematology outpatients clinic daily. But, I was told, I had been admitted to the oncology ward so that I could get into a bed quickly if I was feeling bad and particularly if I caught an infection. After five days, with my neutrophil count on the way down, it was time to go to the ward. Neutrophils are a kind of leukocyte blood cell. They combat bacteria and funguses.

After seven hours in the outpatients clinic and another hour in an oncology ward waiting room, I was in a bed.