Uncalloused white hands shake brown hands, somewhat reluctantly. A golden lion with a triumphant grip on a sword, emblazoned on a flag, is hoisted high.

Sri Lanka (then called Ceylon) celebrated its independence from British rule on 4 February 1948. However, for Tamils and other minorities on the island, the day was just another instance of one oppressor handing the reins to another.

There are four major groups in Sri Lanka. The north and east of the island are the traditional homelands of Tamil-speaking people—Hindus, Muslims and Christians—who make up around 25 percent of the country’s population. It’s important to note that while many Muslims are Tamil-speaking, they are a distinct ethnic identity. In the south and west, the Sinhalese dominate. They make up 75 percent of the total population and are largely Buddhist.

Merging the Tamil and Sinhalese homelands together in 1883, the British imposed a unitary state over the entire territory, consolidating historically distinct ethnic and cultural kingdoms into one, under the rule of a white supremacist capitalist force. It was a tried-and-true strategy for coloniser nations and served the British well for more than 100 years.

Post-independence, the unitary structure allowed the Sinhalese majority to control the affairs of the whole island, and therefore the Tamil homelands, without requiring the consent of Tamils. Independence and democracy did not apply equally to all.

Regaining self-determination within our homelands, named Tamil Eelam, has been the key political goal for generations.

In 1956, the government passed the Sinhala Only Act, which made Sinhala the official language of the country. This made it incredibly difficult for Tamil-speaking people to get government jobs and was one of the key post-independence acts that laid the groundwork for ongoing Tamil oppression, as well as creating the conditions for a liberation struggle. It was not long after the passing of this act that regular pogroms (racially motivated attacks against Tamils) began.

My Amma (mother) told me about a riot she witnessed. It was August 1977, and there were severe pogroms across the country, in which hundreds of Tamils were killed, many raped and 40,000 displaced. Sinhalese rioters broke into Tamils’ houses to loot, kill and burn. One of my Amma’s neighbours, a Sinhalese man, helped my family by harbouring them in his house. There are touching accounts of solidarity like this despite the anti-Tamil racism that was sponsored by politicians and Buddhist monks.

Tamils label as “black days” the most severe instances of oppression and violence. Lest We Forget, a two-part document by the NorthEast Secretariat on Human Rights, details 149 massacres witnessed from 1956 to 2008.

The most well-known pogrom is called Black July, which was carried out primarily in the south of the island by violent mobs in 1983. Perhaps 3,000 Tamils were massacred—many were burned alive. Tens of thousands more were forced to flee to the north and east.

The pogrom was organised and aided by government officials, who had lists of Tamil houses and businesses. The mass exodus of Tamils resulting from this event displaced families like mine, who fled to countries that often were engaged, in various parts of the world, in the same sort of violence that Tamils were fleeing.

The forced displacement of Tamils and the settlement of Sinhalese populations on our lands, a process called Sinhalisation, is a concerted strategy of the Sri Lankan state. The method was noted in the Oakland Institute’s recent report, Endless War: The Destroyed Land, Life, and Identity of the Tamil People in Sri Lanka:

“The main objective of this colonization is to increase the Sinhalese population in the north and east to change the demographics of the regions. One clear tactic has been to divide the geographically and ethnically connected Northern and Eastern Provinces and erase the homeland doctrine of the Tamil people. In the 30 years prior to 2009, these areas were under LTTE [Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam] control that prevented land grabbing.”

And as the authors of Lest We Forget note:

“Massacres were only a part of the ethnic cleansing program carried out by the Sri Lankan state against the Tamils. Huge swaths of land that traditionally belonged to the Tamils were settled by Sinhala people who were brought there from faraway places in the Sinhala areas. Tamils were disenfranchised en masse and stripped of their language rights. The list goes on.”

Yes, the list continues. Tamils are murdered every year, even thirteen years on from the military defeat of the LTTE and the genocide of more than 140,000 Tamil civilians in government-designed “no fire zones”. Many refugees living in Australia, some of whom are still stuck in detention, carry the trauma of being subjected to heinous acts, or of witnessing them being carried out against their kin.

4 February will mark 74 years since Sri Lanka gained independence. In this time, the oppression of Tamils by the army, the police, the law and the bureaucracy has evolved. But the fundamentals remain the same.

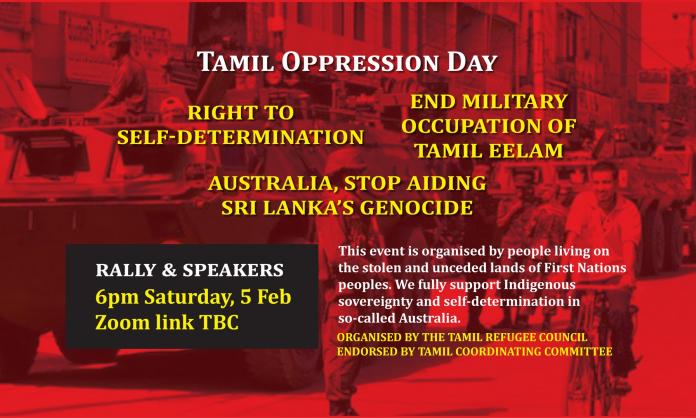

On Saturday 5 February at 6pm, the Tamil Refugee Council will host an online event to highlight the ongoing crimes committed by the Sri Lankan government against Tamil speaking people, to demand the pursuit of justice, and to acknowledge the situation facing Tamil refugees worldwide.