COVID is tearing through the population, filling our hospitals and overwhelming our ambulance services. Elective surgeries in Victoria and New South Wales have been cancelled, and emergency waiting rooms are overflowing, leaving even non-COVID patients waiting dangerously long times to be treated.

It’s a disaster—and a disgrace that nothing was done to prepare the system for such stress. But we should never forget how bad it was prior to the Omicron wave, and even prior to the pandemic. The system was already in crisis.

In COVID-free Perth, the avoidable death last year of young Aishwarya Aswath at the Children’s Hospital highlighted the problem of dangerous workloads. Aishwarya died of sepsis because the emergency room was understaffed and essential triage staff were taken away from their posts to assist with the massive workload on the emergency room floor.

Every nurse or doctor who read about the case knew exactly the situation the staff were in, because we experience it every day, in hospitals all over the country.

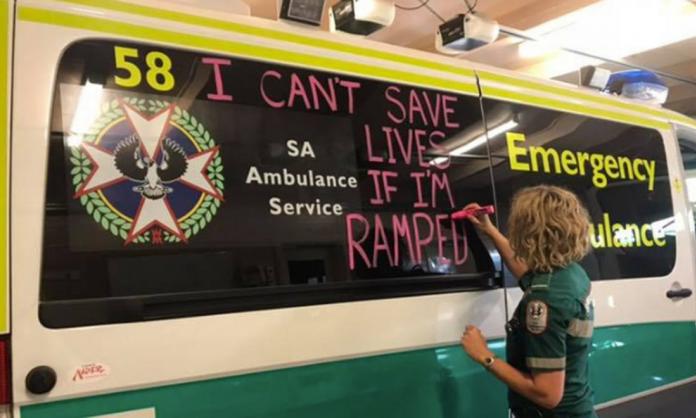

Similarly, in South Australia last year, during its COVID-free run, paramedics were frequently sounding the alarm on “ramping”—ambulances having to wait with patients outside emergency rooms because there are no free beds. Josh Karpowicz from the ambulance union said at the time: “The solutions are clear: there needs to be an immediate and substantial increase to ambulance resourcing and in-patient bed capacity across the state”.

The story is the same in all states. Ambulance ramping is frequently cited as a major issue in Queensland, Victoria and New South Wales. The main culprit is the lack of emergency room beds.

Overcrowded hospitals and emergency rooms in New South Wales have long angered nurses and paramedics. In June 2019, the Sydney Morning Herald reported that patients were experiencing drastic increases in waiting times compared to previous years.

In fact, a quick Google search for articles from before the pandemic returns hundreds of stories of burned-out, angry and frustrated nurses, paramedics and doctors, all sounding the alarm on the dire state of our hospital systems and emergency departments all across Australia.

The narrative that our healthcare system has only just now buckled under the weight of COVID is misleading, and, ironically, lets the politicians off the hook. It’s not just that they “should have known” what the pandemic would bring; it’s that they knew long ago that the system was already breaking.

There have been extra funding announcements in recent times. But much of the extra money pledged does nothing to address the issue of beds and overcrowding. Much of it will go to public health spending and administrative costs, and what does make it to hospitals will go to overtime wages and so-called elective surgery “blitzes”.

It’s bandaids for broken legs. Imagine if a nurse did that. But politicians get away with it again and again.

In fact, the elective surgery blitzes and all of the catching-up work has actually made healthcare workers even more exhausted during the past two years. Even when there have been breaks in the pandemic, with periods of zero or near-zero cases, hospital staff have never stopped.

Elective surgery backlogs mean that, between COVID waves, we have been frantically catching up on lost time. All of the cancelled elective surgery lists need to be caught up eventually. And the workload simply piles up. More surgeries mean faster patient flows, higher turnover and more overtime.

For decades, there has been a trend to run hospitals more and more like highly efficient production lines, with shorter patient stays and therefore higher turnover. A study published in 2020 by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare found that the number of hospitalisations was rising at double the rate of population growth. At the same time, the length of hospital stays was getting shorter and the number of day-stays was increasing.

It’s not uncommon to see young patients with appendicectomies (the surgical removal of the appendix) discharged on the day of their surgeries, hastened by frantic bed managers desperately trying to find beds for all the patients in the crowded emergency rooms.

Such rapid turnover of patients takes an incredible toll not only on nurses, cleaners and allied health staff, but also on junior doctors. The amount of time, effort and administrative work required to admit, and also to discharge, a patient means that junior doctors are working longer hours than ever.

In 2021, an Australian Medical Association survey found that junior doctors on average were performing sixteen hours of weekly overtime. This was overwhelmingly unpaid. Some junior doctors reported doing as many as 25 hours of unpaid overtime per week. This level of stress takes its toll. The Australian Medical Journal reported last year that one in five junior doctors had contemplated suicide. Among female doctors, the suicide rate was more than twice that of the general population.

None of this is going unchallenged. Paramedics and nurses have been involved in industrial disputes recently in New South Wales, South Australia and Western Australia. Junior doctors in Victoria, New South Wales and South Australia are engaged in massive class action lawsuits for unpaid overtime wages.

The pandemic may indeed prove to be the (very large) straw that breaks the camel’s back when it comes to how much healthcare workers are willing to tolerate. What we need now more than ever is a coordinated campaign across the country, involving all healthcare workers: a campaign to increase funding to the public hospital system, to divert the hundreds of billions of dollars that are being committed to military hardware, and to make our governments spend the money on our public healthcare system instead.