As Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine proceeds, protests have continued in cities across Russia. This is despite more than 10,000 arrests and protesters facing fines and even jail time. Millions have signed anti-war petitions and open letters, and anti-war graffiti is appearing everywhere.

In Ukraine, alongside the armed resistance, there is fraternisation taking place between Ukrainians and Russian soldiers. Brave Ukrainian civilians blockaded advancing Russian tanks outside Zaporizhzhia, a city in the south-east, and hundreds protested several hundred kilometres away in occupied Kherson, imploring Russian soldiers to leave. There are growing reports that Russian soldiers, many of them young, poorly paid conscripts who were told they would be welcomed as liberators, don’t want to be there, and are even taking measures to avoid fighting.

It is too early to predict how any of this will play out, but the actions taking place are part of an inspiring history of how imperialist wars can be stopped: through protest and resistance, including in the imperialist countries and armies themselves.

Wars happen because capitalism is a competitive, dog-eat-dog system. The ruling classes of different countries routinely see it as in their interests to wage war for geopolitical advantage. They send the working class to do the fighting and dying for them. This is why appeals to international diplomacy to end wars are ultimately misguided—they are appeals to the same people who start the wars, and for whom the wars, no matter how destructive for the mass of humanity, are often rational.

The only way wars come to an end within this framework is through the victory or surrender of one side, usually meaning millions killed, the devastation of entire cities and “peace” taking the form of grinding occupations. Until the next war breaks out. As one US strategist wrote recently in the Guardian about Ukraine: “If we boil it down, there are really only two paths toward ending the war: one, continued escalation, potentially across the nuclear threshold; the other, a bitter peace imposed on a defeated Ukraine”. But there is a powerful history of mass resistance and working-class rebellion against war and the system that causes it, which shows the potential for another way.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the United States waged a horrific war against the Vietnamese people, who were fighting to free their country from imperialist domination. Despite the rhetoric we hear today, Russia isn’t the only blood-soaked empire in the world. The West killed around 3 million people in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, massacring entire villages and using chemical weapons whose effects are being felt to this day. Some of the weapons today decried as war crimes when used by Russia, like cluster bombs and thermobaric explosives, were developed and widely used against the Vietnamese population (and later against the Iraqi and Afghan populations).

But it is worth remembering how the war was stopped and the US defeated: by heroic Vietnamese resistance combined with mass rebellion in the West, including among the soldiers themselves.

In Vietnam, the US Army, the most powerful killing machine the world had ever seen, faced off against peasant guerrillas armed with old rifles and home-made grenades made from Coke cans. But the resistance was a mass popular mobilisation that couldn’t be defeated and wouldn’t go away, despite the terrible carnage that the US inflicted. The famous Tet Offensive in 1968 epitomised this—a coordinated surprise attack by some 80,000 Vietnamese fighters against more than 100 US-controlled cities and bases. The attack was repelled, but revealed the depth of popular hatred for the Western invasion and exposed the lies that the US was fighting to “liberate” the population.

In the West, the war was beginning to be seen for what it was: a brutal slaughter for US imperialism. In 1965, anti-war university students and staff began to hold mass “teach-ins” to discuss the war. The largest took place at the University of California, Berkeley, with 36,000 participating in a teach-in that lasted 36 hours. In Australia, the anti-war movement kicked off with thousands of maritime workers going on strike and refusing to handle cargo associated with the war. Students were central to the movement in Australia too, with universities becoming anti-war organising hubs and sites of dramatic protests.

In one scene in Sydney, draft resister Mike Matteson, who had been speaking at anti-war events in the city, was followed by two police, who jumped into his car and handcuffed him. But before police could get him out, the car was driven into Sydney University. Within ten minutes, a crowd of nearly 1,000 students surrounded the handcuffed trio, chanting “no conscription!” Bolt-cutters appeared, Matteson escaped, and the police had to retreat, with handcuffs still around their wrists and their tails between their legs.

The anti-war movement was a key driver of the late 1960s radicalisation that drove mass strikes and revolts across the world. People’s illusions in Western “democracy” and parties such as the US Democrats, which escalated the war and viciously attacked anti-war protesters, were being shattered. Hundreds of thousands of people began to see themselves as revolutionaries.

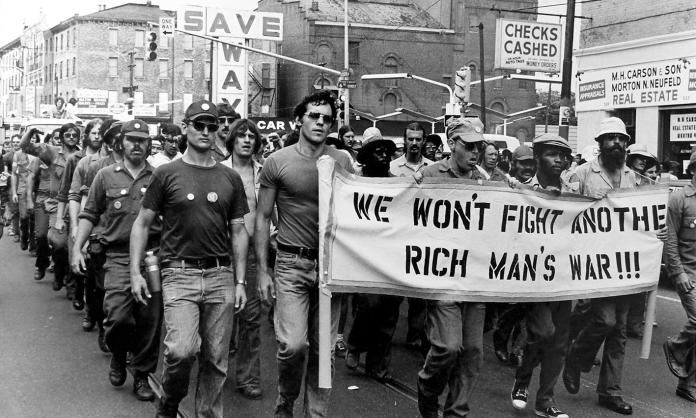

By 1969, millions were marching against the war. In 1971, 71 percent of Americans told pollsters that Vietnam was a “mistake” and 58 percent thought the war was “immoral”. The anti-war movement restricted the number of troops the West could send into the meat grinder of Vietnam, and had US authorities worried that continuing the war abroad could mean civil war at home. It also gave confidence to the growing rebellion in the US Army.

War is hell, and many of the working-class soldiers sent to fight instead rebelled. Some 30,000 Americans fled to Canada or Mexico to avoid the draft. Some spent years in prison for being draft resisters. Others refused orders, organised underground anti-war newspapers or even killed their own officers.

A member of the anti-war group Vietnam Veterans Against the War, Bill Branson, explained:

“A lot of us had really expanded our concept of what was going on ... We were really identifying with the Vietnamese, as not only people who were being oppressed, but they were the ones who were right. We started to get an understanding of imperialism. We became anti-imperialist. We started to see that there was a rich class that was behind this. We saw that it wasn’t just going on in Vietnam. It was going on in the United States.”

By 1971, Colonel Robert Heinl could write in the Armed Forces Journal: “By every conceivable indicator, our army that now remains in Vietnam is in a state approaching collapse, with individual units avoiding or having refused combat, murdering their officers and non-commissioned officers, drug ridden, and dispirited where not near mutinous”. The US had lost, was forced into a humiliating retreat, and was unable to launch a full-scale invasion of another country for decades.

The greatest anti-war movement the world has seen was undoubtedly that which ended the First World War. The Great War, as it was called, was the culmination of sharpening imperialist tensions between the old powers of Europe. Germany, as a rapidly industrialising state that was outgrowing its national boundaries, butted up against the existing empires of Britain, France and Russia. Germany sought to redivide the spoils of exploitation and colonialism, while the others sought to preserve or expand their sprawling empires.

Whipping up nationalistic fervour, and conscripting huge armies of workers and peasants, governments sent tens of millions to slaughter each other across much of the world. The war was initially supported by a majority in every country, but it didn’t take long for the terrible reality to spark resistance. As early as Christmas 1914, 100,000 soldiers along the Western Front paused the carnage, laid down their weapons and fraternised in no man’s land, sharing stories, singing, playing football and collecting their dead.

This act of internationalism was greeted with outrage by the military commanders of every side. News of it was censored, and any further attempts severely cracked down upon. The cannon fodder of every country realising their common class interests was the greatest threat to the rulers of Europe and their whole capitalist order.

On the home front, strikes began breaking out everywhere from 1915, as inflation was biting into working-class living standards while capitalists made huge profits from war contracts. At Easter 1916, Irish rebels revolted against the British empire. In Germany, 55,000 metalworkers struck in Berlin in support of Karl Liebknecht, a revolutionary socialist who had opposed the war in the Reichstag, defying the pro-war line of the Social Democratic Party, and who was then on trial for treason.

In Australia, a huge working-class anti-conscription movement won two referendums, in 1916 and 1917, defeating attempts to introduce conscription. This was an incredible victory against a determined ruling-class campaign that denounced the “antis” as German agents, “Irish dogs” and communist saboteurs.

An anti-conscription protest of nearly 100,000 people in Sydney’s Domain (out of a population of just 760,000 at the time), successfully fought off violent right-wing attacks, and put the pro-conscription forces on the back foot.

In February 1917, the Russian monarchy was overthrown by a workers’ revolution, sending shock waves around the world. Thousands of soldiers from all sides were deserting, a crime punishable by death. Mutinies of soldiers broke out in Italy and France. By 1917, a million French soldiers had been killed, and nearly half the French army was affected by mutiny.

The decisive turning point was the October Revolution in Russia. In most countries, the workers’ movement was dominated by the reformist social democratic parties that in 1914 had betrayed the working class and supported the imperialist slaughter. But the revolutionary Bolshevik Party had opposed the war from the start, and became the leading force in the Russian working class.

In October, Bolsheviks led the workers and soldiers in overthrowing a capitalist provisional government. One of the first acts of the new revolutionary workers’ government, led by Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky, was to pull Russia out of the war, demand an immediate and unconditional peace, and publish secret treaties documenting how Britain, France and Russia were planning to carve up the world and seize even more territories in the event of their victory, contrary to their claims about only fighting for “defence”. The thousands of German prisoners of war held in Russia were released, many heading home full of revolutionary inspiration.

Initially, the rulers of Germany rejoiced that Russia had been taken out of the war. But the Russian Revolution showed the way to workers of all countries: end the war by rising up and replacing capitalist rule with the rule of workers. A year later, German workers and soldiers were following their Russian comrades. A sailors’ mutiny sparked a nationwide revolution. The war was finally ended.

Tragically, the workers’ revolutions that ended World War One were defeated. Capitalism was restored, and the basis was laid for another century of imperialist wars. Today neither the billionaires who rule Russia, nor those who rule the US, Australia or any NATO power, are motivated by concern for the people of Ukraine, still less for “freedom” or “democracy”, but only by their own imperialist interests. Western governments are using Russian aggression as an excuse to boost arms spending, while painting Western imperialism as the good guys, and laying the basis for a conflict with China.

We must reject both Russian and Western imperialism. The history of anti-war struggles and working-class internationalism should be our guide today. Such struggles can end a war. And if they go all the way to overthrow capitalism, they can end wars once and for all.