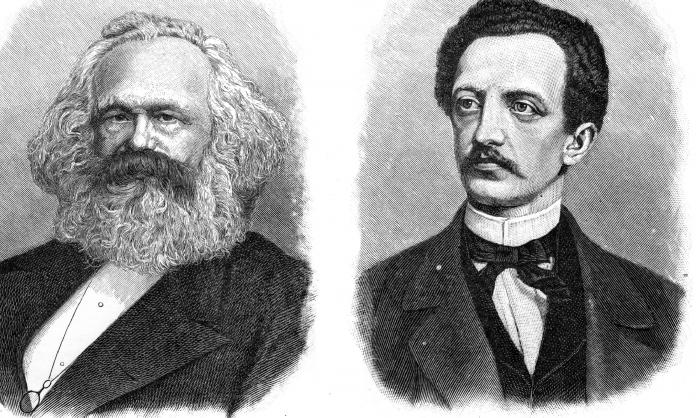

Ferdinand Lassalle (1825-64) is often described as the “founder of German social democracy”. But his influence on the German workers’ movement was mostly disastrous.

Lassalle participated in the 1848 revolution, for which he spent a year in prison. But he was not at all the workers’ champion. Frederick Engels said, in an 1891 letter to Karl Kautsky, that until 1862 Lassalle was “a specifically Prussian vulgar democrat with strong Bonapartist leanings” before “he suddenly switched round for purely personal reasons”. Lassalle tried unsuccessfully to assume leadership of the main bourgeois party, the Progressives. His hatred of the liberal bourgeoisie and subsequent turn to the working class were largely due to his resentment at the liberals’ rejection of him.

In the 1860s, there was a revival of struggle in Europe, as the working class recovered from the defeats of 1848. This made it possible to establish an international workers’ organisation, the First International, in which Karl Marx and Engels were key players.

In the early 1860s, the German workers’ movement was starting to organise, notably in Leipzig. But lacking in experience and self-confidence, these workers felt the need for a spokesperson and turned to Lassalle. Still smarting from his rejection by the liberals, Lassalle saw an opportunity to put himself at the head of this burgeoning workers’ movement and use it as a vehicle to advance his own ideas. He founded the General German Workers’ Association (GGWA) in 1863 and ran it as a dictatorship.

Lassalle was killed in a duel in 1864, but his ideas had quickly become hegemonic in a section of the German movement. Marxist writer Hal Draper commented that, by the time the First International was established in 1864, “the German field had already been pre-empted by Lassalleanism”. Under Lassalle, the new movement “was cradled in the swaddling clothes of a bureaucratic dictatorship, nurtured on state-cultist politics, and educated in the spirit of the Cult of the Individual Leader”.

The centrepiece of Lassalle’s ideology was “state socialism”. Like the philosopher Georg Hegel (whom he studied at university), he believed that the state’s mission was to accomplish the development of human freedom. The role of workers’ or popular movements was essentially to pressure the state into fulfilling its historic role. Marx, having long since rejected the idea that the state could be any kind of progressive force, argued that “state socialism” was a form of reformism.

For reformists, social change comes about through tinkering with the existing state. But for Marx, the question is who controls society—that is, which class rules the state. Therefore, the aim must be a change in class power. Uncompromising hostility to the state, the instrument of the class that rules society, was central to Marx and Engels’ thinking—even before the 1871 Paris Commune demonstrated in practice that workers couldn’t simply take over the existing state but had to smash it and replace it with a new kind of state.

For Lassalle, however, the state was “the immemorial vestal fire of all civilisation”. And he drew no distinction between his idealist conception of the state and the oppressive nature of the state as it actually existed.

In practice, this meant siding with reaction. As Draper pointed out in the fourth volume of his monumental Karl Marx’s theory of revolution, “in 1862 reformists still had a choice between contending ruling classes, the old one still in control of the state [the feudal aristocrats] and the new one dominating the economy [the capitalists]. Lassalle chose the power that still visibly monopolised the state machine”. That is, he looked to a state that rested on the old reactionary class; concretely, he tried to form a secret alliance with Prussian Chancellor Bismarck against the liberal bourgeoisie.

In May 1863, Lassalle wrote to Bismarck. He boasted of his dictatorial powers within what he openly called his own “empire” (the GGWA), and asserted that “the working class feels an instinctive inclination towards dictatorship if it can ... be persuaded that the dictatorship will be exercised in its interests”. He proposed an anti-bourgeois coalition: an alliance between king, aristocracy, army and his workers’ movement.

Lassalle described his personal dictatorship of the workers’ movement as “on a small scale the prototype of our next form of society on a large scale”, without the nasty “malcontent spirit” and “individual opinion” that characterised liberalism.

Nothing came of Lassalle’s secret dealings with Bismarck, which were exposed after his death. Engels commented to Kautsky that they “would certainly have led him to the actual betrayal of the movement, if fortunately ... he had not been shot”.

Lassalle propounded what he called the “iron law of wages”, based on Malthusian population theory. “Under the rule of the supply and demand of labour”, he wrote, “the average wage always remains reduced to the necessary subsistence level ... needed for eking out a living and for propagation”. Wages could not rise above the average for any length of time, as the working population would increase, bringing wages down again. On the other hand, wages could not remain for long below subsistence level, as poverty would lead to a reduction in the number of workers, and thus the supply of factory hands.

But if this were a natural law, Marx argued in his Critique of the Gotha Programme, it couldn’t be abolished, because it would govern “not only the system of wage labour but every social system”. The so-called law simply allows bourgeois economists to argue that “socialism cannot abolish poverty, which has its basis in nature, but can only make it general”. As Engels noted in a letter to August Bebel in 1875, “Marx proved ... in Capital that the laws regulating wages are very complicated ... they are in no sense iron but on the contrary very elastic”.

The political conclusion arising from Lassalle’s “iron law” is that workers cannot improve their conditions of life through their own efforts, so there is no point engaging in collective economic struggle or forming trade unions. Lassallean logic suggests that the only way workers can be freed from the “iron law of wages” is to become their own employers.

And how do they do that? Lassalle’s solution was massive state loans to found large-scale cooperatives that would eventually take over all industry and all branches of the economy. This process would, at some point in the distant future, lead to socialism. So the state, rather than the working class, was to be the agent of social transformation, and no revolution was required. The central demand of the movement therefore had to be for universal (male) suffrage. Indeed Lassalle argued that it should be the only demand of the workers’ movement. He exhorted his followers to “be deaf to all that is not called universal and direct suffrage”:

“When [universal suffrage] comes ... there will be at your side men who understand your position and are devoted to your cause—men armed with the shining sword of science, who know how to defend your interests. And then you, the unpropertied classes, will only have yourselves and your bad voting to blame if the representatives of your cause remain in a minority.”

These “men armed with the shining sword of science”—men like him!—would then legislate to ensure that the state provided the loans to set up producers’ cooperatives.

Lassalle believed that while state aid did not in itself amount to socialism, it nonetheless contained the “germ” of it. The state and its rulers were presumably not expected to understand this; otherwise they would hardly finance their own demise. But workers weren’t expected to understand it either!

Lassalle’s approach—not just socialism from above, but socialism by stealth—is the polar opposite of the conscious self-emancipation of the working class.

Marx condemned the Realpolitik of Lassalle, whose idea of practicality was to conform to existing conditions. But he understood its appeal to a working class that was still demoralised by a long period of reaction, and so was ready to “hail such a quack saviour, who promised to get them at one bound into the promised land”.

After Lassalle’s death, Marx and Engels set out to fight his ideas within the workers’ movement. They opposed the Lassallean project of getting state capital for producers’ cooperatives, on the grounds that this would only help the government extend its tentacles into the workers’ movement.

As Marx wrote in letters to Engels: “The Prussian state can not tolerate workers’ coalitions and trade unions ... In contrast, government support to a few lousy cooperative societies is just the kind of crap that suits it. It means extending the noses of officialdom ... corrupting the most active of the workers, emasculating the whole movement”. Lassalle’s “hapless illusion” that “a Prussian government would carry out a socialist intervention” was doomed to disappointment; and “the honour of the workers’ party requires that it reject such illusions, even before their hollowness is punctured by experience. The working class is revolutionary or it is nothing”.

In January 1865, Marx had written to J.B. Schweitzer, now leader of the GGWA, “telling him that he must array himself against Bismarck, that even the appearance of a flirtation with Bismarck on the part of the workers’ party must be dropped”. But in the 1866 election, the GGWA supported Bismarck’s candidacy. By this time, Marx and Engels had resigned as contributors to the GGWA’s publication.

Lassalleanism declined as the political power of the bourgeoisie grew and its weight within the state increased. By 1875, there were discussions about the possibility of unity between Lassalle’s followers and the Eisenachers—the group led by August Bebel and Wilhelm Liebknecht, who saw themselves as Marxists and had founded the Social Democratic Labour Party in 1869.

Marx believed that the Lassallean forces were being forced towards a merger because of their weakness on the one hand, and the growing independence of trade unions and influence of the Social Democrats on the other. Nonetheless, his preference was not for a united organisation, but for a period of common activity, a kind of united front. The vital step, in his view, was not agreement on a common programme but rather the advancement of the workers’ movement: “Every step of real movement is more important than a dozen programs”, he wrote in a letter to Wilhelm Bracke.

But Bebel and Liebknecht succumbed to impatience and opportunism, viewing organisational unity as a shortcut. At a conference in Gotha in 1875 the two organisations merged to form the Socialist Labour Party of Germany under a draft program that made huge concessions to the Lassalleans. The programme pledged that the party would work “by every lawful means to bring about a free state”. It contained none of Marx’s analysis of economic development, no word of revolution, no discussion of the class character of the state. Unity was achieved at expense of political principle.

Marx wrote a savage critique of the Gotha programme, which he described as “for all its democratic clang ... tainted through and through by the Lassallean sect’s servile belief in the state”. To summarise his main objections:

First, the programme dealt with the state “as an independent entity”, whereas the German state in question rested on a reactionary class. The programme “attacked only the capitalist class and not the landowners” and described all classes other than the working class as “one reactionary mass”. This Lassallean distortion was used to “put a good colour on his alliance with absolutist and feudal” forces.

Moreover, the workers’ movement was viewed, again following Lassalle, “from the narrowest national standpoint”. Marx argued that working-class struggle is national only in form, not substance. The national state exists within the framework of the world market and the system of states. The programme thus reduced internationalism to “the international brotherhood of all peoples”, with no class content.

Second, the programme enshrined the slogan of “cooperative societies with state aid ... on such a scale that the socialist organisation of the total labour will arise from them”. Marx’s response was scathing: “It is worthy of Lassalle’s imagination that a new society can be built with state loans just as well as a new railway!” Marx didn’t oppose cooperatives per se, or oppose making demands on the state. But he objected to such reforms being held up as the goal, a substitute for a rounded socialist programme.

For Marx, reformism does not simply mean the advocacy of reforms, but rather “assigning a certain all-encompassing meaning to the fight for reforms, its elevation to the be-all and end-all of politics”. Marxists fight for reforms partly to improve the conditions of workers, but more importantly as a way of developing the consciousness and confidence of the workers’ movement to go beyond reforms and challenge the capitalist system itself.

As for cooperative societies, “they are of value only in so far as they are the independent creations of the workers and not protégés of either governments or of bourgeois”. The key word there is “independent”.

Similarly, Marx drew out the political meaning of the demand for “state aid”: “Instead of arising from the revolutionary process of transformation of society, the ‘socialist organisation of total labour’ ‘arises’ from the state aid that the state gives to the producers’ cooperative societies and which the state, not the worker, calls into being”.

Thus the Gotha programme, following Lassalle, dispensed with the need for revolution and assigned the basic creative role to the state.

Engels, in his letter to Bebel, also dismissed the idea of the “free state”: “As the state is only a transitional institution which is used in the struggle, in the revolution, in order to hold down one’s adversaries by force, it is pure nonsense to talk of a free people’s state ... as soon as it becomes possible to speak of freedom, the state as such ceases to exist”.

Ominously for the future of German socialist organisation, Marx’s critique was suppressed for years, as were the passages in his writings that were most critical of Lassalle. The Gotha programme was, as Hal Draper described, a “bridge between the state-socialist reformism of Lassalle, which by itself had no future, and the bourgeois reformism of the type that did represent the future of German social democracy”.

Despite the Social Democratic Party’s formal rejection of Lassalleanism and the adoption of the seemingly more radical Erfurt program in 1891, a degree of confusion about the state—and therefore the seeds of reformism—remained within the German party.