“A sense of relief” is how Sudanese political activist Muzan Alneel, speaking via Zoom from the capital, Khartoum, describes the mood on the streets of Sudan in the first hours of the coup on 25 October. “I remember seeing people come into the street singing, like they’re singing against the coup and they’re singing against [coup leader General] Burhan, but they’re singing”, she says.

Relief is not an emotion usually associated with military coups. But in Sudan, people believed the coup to be inevitable. There was a failed coup attempt in September; the coup on 25 October clarified the terms of battle and threw the fight into the open. Relief came from confirming what the revolutionaries had been steeling themselves for.

Resistance was immediate. Bank workers announce a strike at 7am, two hours after the coup began. For weeks they had made it known that they would shut down the country’s financial industry as soon as the military deposed the government. People began building barricades. Neighbourhood committees and social and political organisations called for civil disobedience. By the end of the day, the country was paralysed by a general strike.

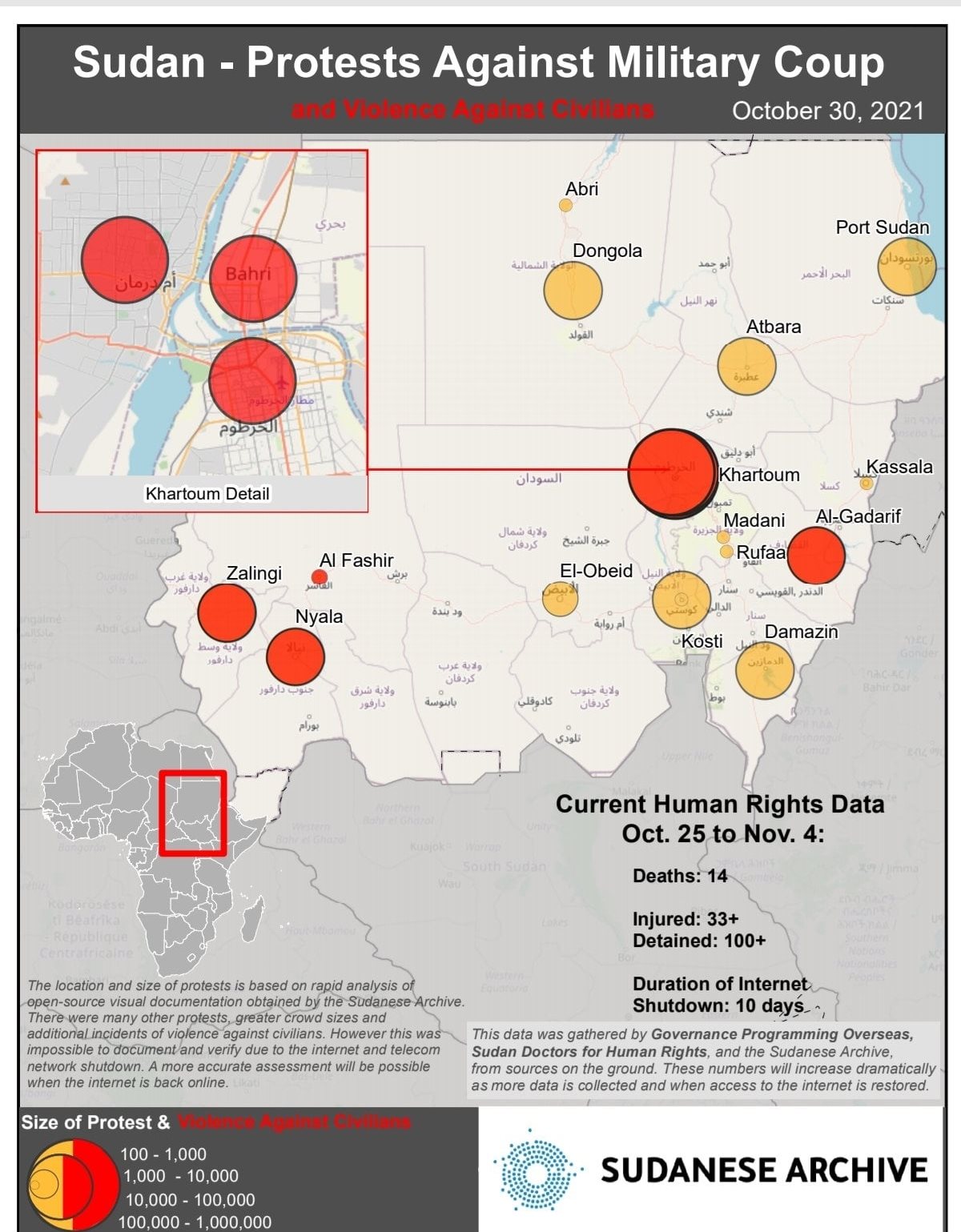

In Khartoum, the military erected their own barricades to stop people marching towards the Military Command, but these were quickly overrun by protesters. Tyres burned across every street and barricades were made more elaborate by the hour: tens of thousands had responded immediately to the military’s move. “Let’s have it. Let’s have this fight. Let’s be done with it”, is how people saw the coup, Alneel says. It was a battle that had “been delayed for way too long”.

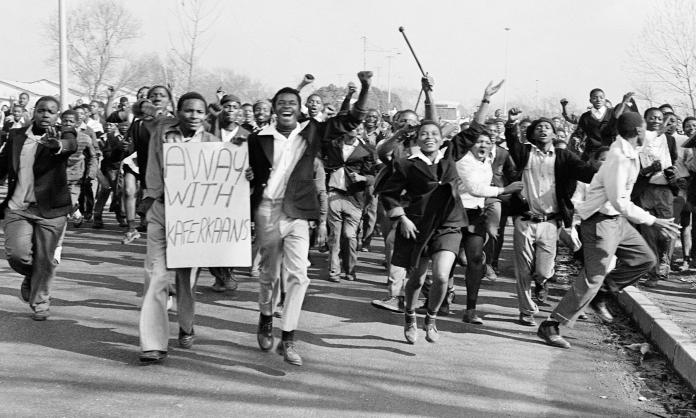

The crisis has its roots in the revolution that swept the country from December 2018 to mid-2019. That movement began when the ruling National Congress Party’s headquarters in Atbara was burned down by students protesting the five-fold increase in the price of bread. The protests spread, with people initially outraged by the cuts to fuel and bread subsidies, and eventually climaxed with a months-long sit-in outside the Military Command in Khartoum. Omar al-Bashir, the despised dictator of 30 years, was deposed by the military in April. His replacement, Lieutenant General Ahmed Aban Ibn Auf, lasted just 24 hours before the pressure of the movement forced him to step down.

The leadership of the revolution, a political coalition led by the Forces of Freedom and Change, entered negotiations over a transition to democracy. The result was a civilian-military coalition, called the Sovereignty Council, that has ruled the country for the past two years.

Protesters did not accept the compromise with enthusiasm. On 3 June 2019, prior to establishment of the Sovereignty Council, security forces had attacked the sit-in outside the Military Command, killing, raping and injuring hundreds of people. Strikes erupted in response but were quickly called off by the Sudanese Professionals Association, an umbrella group of more than a dozen white-collar and professional unions.

The Professionals Association led the movement on the ground and was the key force in the Forces of Freedom and Change coalition. Its influence was instrumental in demobilising the revolution and selling the military-civilian compromise. The Professionals Association’s closeness to the protesters, and its reputation for organising resistance to the regime, gave it a credibility that the other political forces lacked.

Calling off the mass movement and instead negotiating with the criminals in the military was a betrayal of the revolution. General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, who became chairman of the Sovereignty Council and now leads the country, was a political ally and army commander under al-Bashir. He was a key protagonist of the genocidal campaign in Sudan’s western region of Darfur, which killed hundreds of thousands and displaced millions.

Despite the civilian section of the Sovereignty Council having more weight—six votes to five— Forces of Freedom and Change coalition’s strategy was total compromise with the military. Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok implemented austerity measures, such as cutting fuel subsidies, which contributed to crippling inflation on basic goods. The popularity of the civilian section allowed it to sell the agenda of the Sudanese ruling class, despite it being the same austerity that had led to the revolution in 2019.

The military was momentarily forced to concede to civilian rule, but it was never content with sharing power. The Professionals Association helped to create the conditions for the latest coup by channelling the revolution into an asymmetric power-sharing deal. But the hope for democracy in Sudan never lay in the Sovereignty Council, or any deal with the military. Instead, it lies with the strikes and protests that brought down Bashir and Ibn Auf.

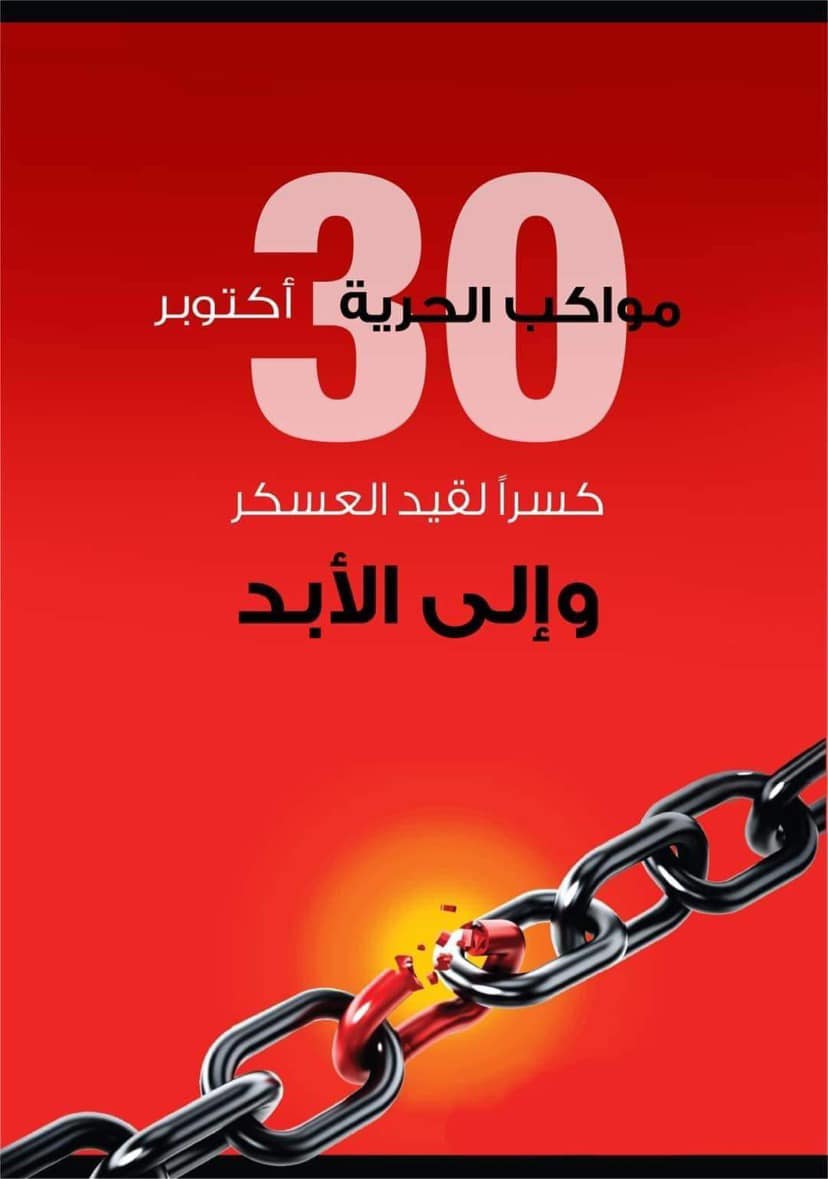

Neighbourhood resistance committees have emerged as an alternative leadership in the renewed movement. They played an important role in 2019 but have become the leading force on the ground today, immediately responding to the coup and organising a “Millions March” on 30 October.

The membership of the committees varies. Because they are geographically based, they can be composed of the unemployed in Khartoum districts such as El-Haj Yousif in the north and al-Kalakla in the south, or wealthier sections of the population in affluent suburbs such as Al Riyadh. Their more grassroots and activist nature, however, makes the committees the most responsive and democratic bodies in Sudan. Many committees have elected leaderships.

An initial challenge they faced was a continuing countrywide internet blackout. They organised mass leafleting and night marches to promote upcoming actions, including the Millions March. They also organise the distribution of food and other necessities, garbage collection, medical supplies and maintenance of the barricades, which are key to stopping the “thatchers”—the security forces vehicles, which are used to arrest activists in their neighbourhoods.

The committees also play an important political role. They released statements popularising the demands of the revolution, which include “no negotiations, no partnership and no bargaining” with the military and the call for full civilian rule. While they are not explicitly political organisations, young revolutionaries are drawn to them as the most effective organisations to fight the coup. In Sudan, political parties are mostly middle class with a legacy of sell-outs and association with the old regime.

Alneel argues that the committees “seem to be the main factor that stopped the coup many times up until now” and “they’re the only [force] creating a threat to the system”. They are the only defence against another compromise. For example, the committees in Greater Omdurman, the country’s largest city, rejected the offer of a closed-door meeting with Hamdok and demanded a public address. A press release, shared on social media, read: “Our position is unequivocal: no negotiations, no compromise, and no power over that of the people”.

The country from 25 October has been engulfed in a general political strike. According to a report on one resistance committee’s Facebook page, in the first week strike participation rates were 91 percent, 96 percent and 100 percent in the oil, banking and education sectors respectively. Similarly high rates have been reported across all industries. Doctors and nurses are refusing to work in military hospitals and treat only emergency cases at civilian hospitals. Committees representing workers in the oil, banking and aviation sectors have put out a coordinated plan for civil disobedience.

The workers’ movement suffered under the Bashir era, and many unions were controlled by the state. With the old dictator’s fall, space began to open for union organising. While the leadership of the Professionals Association preferred the negotiating table, labour activists in the oil, communications and university sectors established democratic leadership bodies that have been organising the strikes, circulating demands and sometimes coordinating with neighbourhood committees.

The success of the revolution depends on these democratic organisations, particularly the independent unions and elected workers’ committees. They have demonstrated that they can bring the Sudanese economy to its knees in a matter of hours, giving the mass movement a power it does not have simply through the resistance committees. But it is too early to know whether they will use this power to provide a political alternative to more compromises.

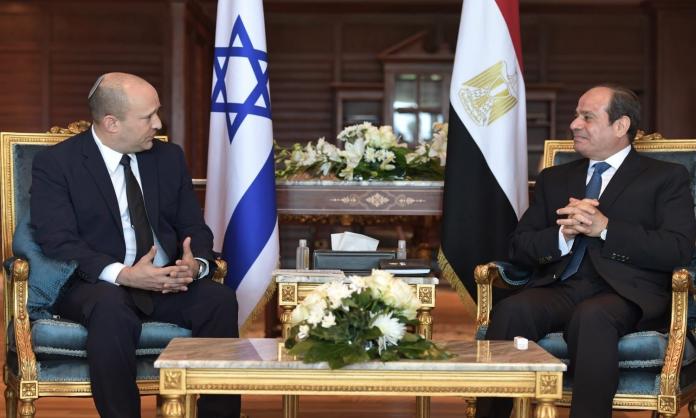

The situation is in flux. In the past week, Hamdok, under house arrest, has met with Volker Perthes, the UN special representative to Sudan, to find acceptable negotiating terms with the military. International pressure for a compromise, particularly from US and Western diplomats, has been intense.

Another limitation is the lack of any revolutionary organisation that could lead the movement clearly against the compromising forces and argue clearly for the working class to lead the revolution.

Despite the challenges, and the repression that has killed at least fourteen in Khartoum, Sudanese protesters have shown courage and resilience. As Alneel remarked about the Millions March on 30 October: “[It] was huge. I haven’t seen anything this big ... We couldn’t even march because the whole street was full”.

MY PEOPLE ARE POWERFUL pic.twitter.com/1BkzKBLocl

— Bashy (@ElbashirIdris_) October 30, 2021

Videos have shown young women proudly leading chants and making public addresses. The elderly are seen with tears in their eyes, hugging young protesters. References to poetry are common among chants and slogans. On the day of the coup, a video appeared of a young man scrawling part of a famous Arabic poem on a billboard. “Whenever people decide to live, destiny will heed them, the darkness will come to an end, and chains will be broken”, he wrote, as many protesters cheered below.

The Sudanese people have decided to live, and they are intent on breaking the chains of military rule for good.