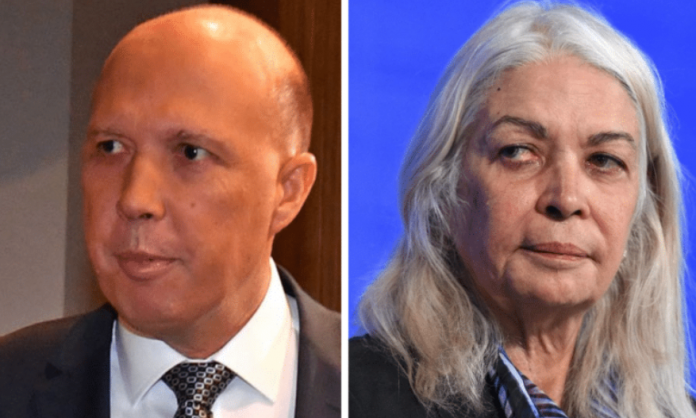

A couple of weeks ago, Marcia Langton—usually one of the more conservative voices in Indigenous politics—became overnight a figure of hatred for Australia’s frothing right-wing journalists and politicians. Why? Because she said something mind-numbingly obvious about the upcoming referendum: “Every time the No cases raise their arguments, if you start pulling it apart you get down to base racism—I’m sorry to say that's where it lands—or sheer stupidity”.

If anything, Langton was too kind. What are the No campaigners saying? Their official booklet, posted to every household, quotes Country Liberal Party Senator Jacinta Price warning that the voice “will not unite us, it will divide us by race”. Just last week, Price went on to deliver a significant speech, nominally about the Voice, which argued that “the acceptance of violence within traditional [Indigenous] culture” was the main cause of Indigenous suffering, and that colonialism couldn’t be blamed. Asked if the colonial invasion of Australia had any impact whatsoever on Indigenous people today, Price responded: “Positive impact? Absolutely!”

So when Britain, and presumably other European powers, invade and dispossess an entire continent’s inhabitants, it’s admirable behaviour. In fact, genocidal violence and theft should be celebrated for their positive impact. But its victims, having had the good luck to be invaded, should be attacked for their “acceptance of violence”. And by the way–beware of anyone who seeks to “divide us by race”. Is this stupidity or racism? Langton says it’s one or the other but she’s clearly wrong: it’s both.

So why has Langton been left to twist in the wind? Labor and its allies in the Yes campaign refuse to say the obvious: Langton is right, and the racism being generated by the No campaign is an abomination. Since Langton’s statements, the right-wing press and the Liberals have been demanding that Labor denounce her. In parliament, Labor’s MPs dodge the question, saying their campaign is about “respect” and “listening”—meaning they respect the No campaign, and don’t think anyone should describe it as racist. “There must be a mutual respect here. We must be guided by love and by faith”, was all Minister for Indigenous Australians Linda Burney could come up with.

It’s a cowardly evasion. As the white-power wing of the Australian right pounces on anyone who tells the truth, Labor remains motionless, hoping it won’t be the next target. No doubt Labor’s campaign strategists are worried that if they tell the truth, they’ll alienate No voters. Maybe they don’t want to start a real debate about racism, given the complicity of state and federal Labor governments in the historical and ongoing oppression of Indigenous people. But as they fret over their electoral maps, they should consider the consequences that will flow from demanding “respect” for one of the most astonishingly brazen racist publicity campaigns of recent decades.

The “No” campaign, in both its official and unofficial wings, is really based on two ideas. The first is that the Voice—basically a toothless advisory committee, unlikely to serve as much more than a decoration—represents a terrifying power grab by a powerful and sinister Aboriginal-leftist complex. All the phrase-mongering about the Voice being “risky”, “permanent” and “divisive” is a nod to this sentiment. Anti-Indigenous conspiracy-mongering has a long track record in Australian politics, especially when big landowning interests think that a land rights reform might encroach on their ill-gotten gains. Conspiratorial conservatism has been supercharged since the pandemic, as the right-wing press and Liberal Party branches have slithered closer to the QAnon-style paranoia.

The notion that Indigenous people in Australia are too powerful—that, as one No campaign leader put it, “Aboriginal people will be running this country, and all the white people here will be paying to live here” if the referendum succeeds—is endemic to the No campaign, and it is racist, and it is sheer stupidity.

The second idea underpinning the No campaign isn’t really about the Voice at all. It’s an ongoing project to rehabilitate all the worst aspects of Australian capitalism, to discredit the idea that Indigenous people are oppressed, to wind back the meagre gains of the last few decades, to cheer on continued oppression and blame Indigenous people for their own suffering.

It’s about rewriting history and misrepresenting the present to uphold empire and defend colonisation. The seizure of wealth from Indigenous people, the genocidal conquest of the continent, the ensuing state-directed programs of cultural extermination, all have to be erased from history or repainted as something necessary and noble.

The idea that Australia’s ruling elites had won their position thanks to crimes against humanity is denied; the proposal to redistribute their wealth in favour of their victims is undermined. The British Empire’s victims are portrayed as the lingering remnants of a sick, degenerate culture, in desperate need of a little forcible civilising.

From the 1980s onwards, Liberal politician John Howard campaigned against the “professional purveyors of guilt”, and in government he endorsed the literal rewriting of history by his coterie of “Howard intellectuals” like Keith Windschuttle and Geoffrey Blainey, the better to undermine any of the pitifully underfunded and legally weak programs that sought to ameliorate Indigenous poverty, poor health outcomes and cultural disconnection. Howard’s beloved protegé, Tony Abbott, pursued the same approach, and Abbott’s kindred spirits—commentators like Peta Credlin, or politicians like Opposition Leader Peter Dutton and Price—are continuing his legacy.

That’s why so much of this debate isn’t really about the Voice. For right wingers, the policy proposal has been an excuse to argue that a little genocide never hurt anyone, that white people are being oppressed when they hear a Welcome to Country and that even the tiniest symbolic concession to Indigenous people is too much.

These ideas, too, are racist: they uphold the “civilised” violence of colonialism, while hypocritically denouncing the cultures of those who were victimised by it. They are stupid: they require the denial of basic historical facts and contemporary realities. If we can’t say this, the battle is already half lost. If it’s not racist to uphold genocide and blame its victims, then nothing is racist. If it’s not stupid to say that Australia risks becoming an Indigenous-run dictatorship, then nothing is stupid.

Anyone who fights against racism—and this applies especially to Indigenous people in Australia—will be called divisive, extremist, insulting and abusive. That public calumny begins as soon as you utter the most basic truth: that powerful, “respectable” institutions, whether they be the Liberal Party or the conservative press, promote and cultivate racism. If we can’t even acknowledge this basic reality, we can’t hope to ever understand and defeat racism. When people take this risk, and cop their savaging by the right-wing institutions, they need to be defended.

This isn’t just about Langton, who is, after all, a comfortable, conservative academic, twice honoured by the Queen, generally seen as rather close to the political right and to big mining companies. It’s about the precedent that is being set. If Labor can throw her to the wolves, what will they do for some working-class Indigenous activists with fewer connections and less media training, who try to stand up to a racist boss, a racist government, a racist police force or a racist campaign of media slander?

The Voice referendum has unleashed a vile, racist campaign that conservatives have long wanted an excuse to wage. And it has exposed the absolute incapacity of the Labor Party and its allies to stand up to it.