What a breath of fresh air it was to hear the words “Fuck the police!” at Mardi Gras once again. Senator Lidia Thorpe’s outraged cry was one of the few things at Mardi Gras in 2023 that echoed the original spirit of the event.

Who cares that—after only 38 years—the police apologised to the original protesters! They have never stopped being the enforcers of an unequal status quo. Even this year they were strip-searching people for drugs at Mardi Gras. And, as Thorpe was right to point out, the toll of police-inflicted death and injury of Indigenous people grows greater every week.

It is an absolute disgrace that the cops are welcome in the parade, with not one but two contingents. What’s more, today’s Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras depends for its existence on a multitude of corporate bloodsuckers all too happy to engage in some pinkwashing to cover their real purpose—the pursuit of profit.

The parade itself now bears a remarkable resemblance to the Mardi Gras’ list of partners, from “principal partner” American Express to a cavalcade of corporate scumbags like Coles, Qantas and Meta.

Instead of this cop-loving corporate jamboree, the first Mardi Gras in 1978 began with a protest and ended with running street battles with the cops. It revived the radical activism of the movement that was linked to the Stonewall riots of 1969 in New York.

In 1978, gay activists in the US put out an international call for solidarity action. In Sydney it was socialists Ken Davis and Ann Talve who first responded. A meeting on 20 May of the Gay Solidarity Group planned a demonstration and public meeting for the Stonewall anniversary. It was CAMP (Campaign Against Moral Persecution) executive member Ron Austin and Communist Party member Lance Gowland who proposed the further action—a night-time celebration or “Mardi Gras”, the name given it by Margaret McMann, which stuck.

On the day, the response exceeded the organisers’ expectations. More than 500 people marched through the streets of the city in the initial morning rally. The public meeting also drew a good crowd. But it was the evening event, the Mardi Gras, that took things to a new level.

Hundreds marched from Taylor Square to Hyde Park, singing and chanting for people to get out of the bars and onto the streets. And people did. There were close to 2,000 people by the time the march arrived at Hyde Park.

There, the police tried to shut it down, confiscating the truck and sound system. This only angered the crowd of demonstrators, who boldly marched on.

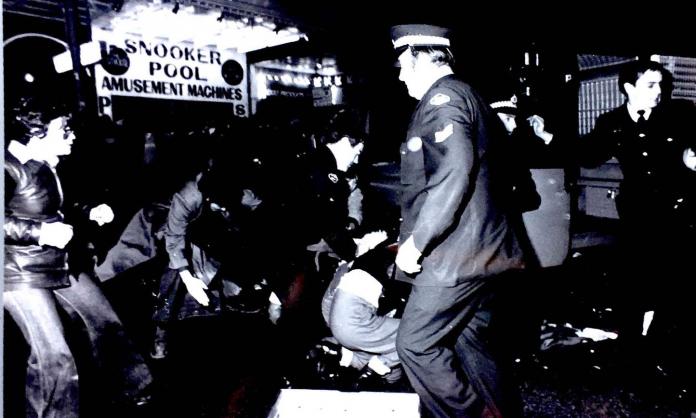

At the El Alamein fountain in Kings Cross, the police went for revenge, determined to violently quash the marchers’ defiance. Gangs of NSW police bashed and arrested as many as they could get their hands on.

Undeterred, those left standing moved the protest to the Darlinghurst police station, where the arrested had been taken. As they heard comrades and friends inside being beaten, those outside kept up a barrage of solidarity chanting, while collections for bail money took place at the cop shop and in activist households across the city.

Activists were not intimidated by the police violence or the fact that Sydney’s polite liberal broadsheet, the Sydney Morning Herald, published the name, address and occupation of everyone arrested.

Instead, it was the start of more protests, beginning with the court appearances two days later, where more were arrested. Thousands marched again on 15 July and 27 August 1978, demanding that all charges be dropped.

The cops tried to put a stop to the wave of anger with mass arrests, taking the total to almost 200. This only further fuelled the “drop the charges” sentiment (many of which the cops did quietly drop in 1979, claiming they’d lost the files). Protesters also demanded the right to march.

The campaign forced the NSW government to repeal all the sections of the hated Summary Offences Act that the police had used to try to stop protests by a wide range of left-wing groups. This was a win for every campaign, and for defiance over compliance.

At a time of extreme homophobia and transphobia, we had to battle the cops and the rest of the capitalist state apparatus—such as the courts and the government— as well as the media and even conservative gay groups.

One of the five 78ers still active in Socialist Alternative today, Mick Armstrong, was arrested at the court protest on 26 June 1978 for the crime of “discharging a missile, to wit, an egg”. As Mick wrote on the 40th anniversary of the Mardi Gras:

“Hundreds of activists, both gay and straight, threw themselves into a vibrant campaign of mass meetings and protests. It was the most impressive campaign for LGBTI rights ever seen in this country and paved the way for many future victories.”

Diane Fieldes is a 78er who marched in the “drop the charges” rally on 27 August 1978 at which more than 100 people were arrested.