What is the background to the constitutional convention and what are some of its limitations?

Camilo: We define the constitutional convention as an institutional exit to the revolution of October 2019. It was proposed when President Sebastian Piñera was completely cornered by the protests, with only a 6 percent approval rating. This was when millions of people were in the streets pressuring him to leave and denouncing the violation of human rights being committed by state security forces.

In quite an intelligent move, the right offered the entire parliamentary political spectrum a pact, which was an institutional exit to the conflict, by proposing the possibility of drafting a new constitution. The demand for a new constitution is a historical demand of the left in Chile. But the proposed convention has a number of limitations.

One is that international free trade agreements will not be touched. This is an enormous limitation on the convention’s ability to change the neoliberal nature of the Chilean model, particularly in relation to extractivism. It’s also very difficult, within this institutional framework, to break with the privatisation of human rights.

This model in Chile has led to the privatisation of water, education, health care and housing. The exclusion of international agreements essentially means that it is not a free and sovereign constituent assembly in which all the issues necessary for a new constitution can be debated.

Another important point is that the electoral system gives far greater representation to the parliamentary political parties. And also, there is the two-thirds rule, whereby every article of the new constitution must be approved by a two-thirds majority. This essentially gives a minority veto power over the final changes.

Why did you decide to form the Anti-capitalist Movement and participate in the constitutional convention?

Camilo: Being highly critical of the limitations and democratic faults of the convention, we decided to participate mainly for two reasons. First, to criticise the limitations of the constitutional convention. And second, to present a platform that represents the revolution of October 2019.

We know that the limitations of the convention make it practically impossible for the key issues to come to the floor. But, regardless, we believe that we have to be there, that we have to denounce it as much as possible, and that we have to start building a single pole of the revolutionary left to be able to push for a truly free and sovereign constituent assembly.

In this respect, we think it’s very possible that once the constitutional convention confronts its own limitations, the streets are going to be revived as a critical voice of struggle, realising and denouncing these limitations.

Maura: It is important to recognise that the rebellion provoked a period of change in our country. This period is marked by the force of the mobilisations and the expression that was given to them in the different assemblies that swept across all of Chile. All of our territory was flooded with diverse democratic spaces that were debating the type of life we wanted.

In that context, there were three general strikes to remove Piñera, particularly the strike of 12 November, which was the most important strike Chile has had in a long time. That strike established a “before” and “after” in the entire process of the regime’s political realignment to save Piñera. Two days later, at the eleventh hour, the Frente Amplio, together with the Pinochet right, signed the Pact for Peace and a New Constitution.

With that being said, firstly, we are launching a strong campaign to put up a new voice. This is because the lesson taken from the rebellion was that what was missing was not the force in the streets or even general strikes to get rid of Piñera. This lesson and the pact came about precisely because what was missing was a strong, anti-capitalist, revolutionary left that could take up the program of the streets.

That program really began in 2006 with the enormous student protests, and continued into 2011 with the struggle for free public education. And in this historical sense, the demands of the streets haven’t been resolved.

All of these demands exploded on 18 October 2019, and came together in the slogan “No son 30 pesos, son 30 años” (It’s not 30 pesos, it’s 30 years) [a reference to a 30 peso increase in metro fares, which touched off the mobilisations]. In this context, and recognising the need to build a new, anti-capitalist, revolutionary left, all of these unanswered demands caused the need for a new political force.

Thus, our main characterisation of the process since October 2019 is that it lacked this left, and that we have to build it. Therefore, our campaign hopes to intervene into this process, even though we have denounced the constitutional convention since the beginning. We have been saying that this wasn’t our agreement. The people never came out into the streets for a constitutional convention.

Actually, the protests had two main demands: Fuera Piñera (Get Out Piñera) and a free and sovereign constituent assembly. These were the key slogans of October. And even though it slowed down due to the pandemic, this period of change remains open. The institutional exit may have saved Piñera, but the crisis remains very deep.

What is your campaign platform?

Maura: There are a number of key policies to our platform. Some of these include: putting an end to the AFP (Chilean private pension system); recognition of domestic work, reproductive work and care work, with a salary in accordance with the cost of living and that is recognised under the social security system; an end to the pillaging of national land; and putting an end to the political class.

In Chile, a politician is paid sixteen times the minimum wage, which creates a huge divide between them and working people. Consequently, we propose that all politicians receive a salary in accordance with the cost of living, equal to a normal worker, and that they be recallable.

We are also fighting for a high quality, free public health system and a progressive end to the private system; a free public education system with a non-sexist, feminist perspective that breaks with gender stereotypes; an end to property speculation, and the universal right to housing; the right to unionisation; and an end to gender violence.

However, the fundamental point of our campaign is about creating a new political project for this new period. Our candidacies are fuelled by workers, local people, students, environmental activists, and others from Santiago and other regions, all striving for an independent, anti-capitalist movement.

Your campaign talks a lot about ecosocialism and feminism. How are you incorporating these ideas?

Camilo: Ecosocialism and class-based feminism are key points of our politics. We understand that capitalism isn’t just a system that degrades the conditions of workers, but also destroys the planet, due to its mode of production. In Chile, this takes the form of an extractivist economy that has absolutely no respect for the environment.

For example, in the Valparaíso region, large monoculture companies growing avocados have completely dried out the valleys because they require so much water. Some types of fruit have completely disappeared because of drought. But this is not a naturally caused drought; it comes from this mode of exploitation of nature.

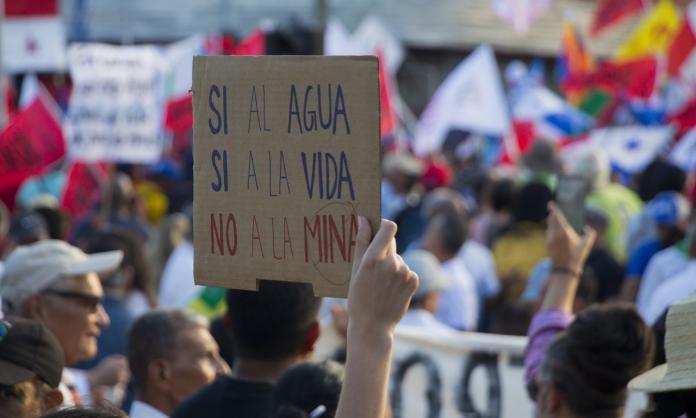

Consequently, one of our key fights is to make water a basic right for human use. Today in Chile, there are private concessions for water use, which has resulted in the use of water essentially being in the hands of a few monopoly companies. So we believe that we cannot propose an ecological alternative without directly attacking the capitalist structure.

Maura: Latin America has a particularity. There is a hugely important upswing in the feminist wave, and Chile and Argentina are the global vanguard of this wave. These mobilisations fundamentally question how capital is reproduced. Here one of the main slogans is “Patriarco, Capital: Alianza Criminal” (Patriarchy, Capital: Criminal Alliance), which the whole feminist movement uses.

In Chile the feminist movement, as in all movements, has distinct tendencies. It includes liberal, separatist, autonomist, socialist and more tendencies. But we understand that we have to meet in the streets and fight for basic questions such as an end to gender violence and control over our sexual and reproductive rights.

Also, the right to land is important. With respect to the extractivist model in Chile, it’s often women who are on the front lines against multinationals, particularly peasant women and women living in precarious conditions. In this context, we see the possibility to intervene with a feminist, anti-capitalist politics that allows us to build the alternative that is required.

What has been the role of the Chilean Communist Party?

Camilo: The Communist Party, which did not sign the Pact for Peace and a New Constitution, has parliamentary representation and has formed government in Chile jointly with the ex-Concertación, that is to say, jointly with the reformist political alliance in the previous government of Michelle Bachelet. When it was in government, the Communist Party did not undertake one truly anti-capitalist policy, or even anti-neoliberal policy, and in fact, formed part of a neoliberal government.

In the context of October 2019, there are two important considerations apart from the fact it didn’t sign the pact. Firstly, the national general strike of 12 November. On this day, Chile was completely paralysed, the main ports of the country were completely blocked by dock workers. The Communist Party, with the United Workers Central, called for an end to the strike at a moment when the regime was seriously weakened. Secondly, its role since the pandemic. In April the Communist Party voted for a law called the Employment Protection Law, which allows large companies to fire their workers without any form of compensation. Due to this law, thousands of workers were fired.

The Communist Party has played a similar role to its role at the end of the dictatorship, remembering that the end of the Pinochet dictatorship was also a negotiated exit through a pact in 1988-89 resulting in a plebiscite. The party has been a massive demobilising force that has put a brake on the revolution, particularly when the streets have been most enraged and demanding that Piñera go. So, although it didn’t join the pact, it is de facto part of the group of parties that protects and defends the regime.

The Chilean constitution is considered the prototype neoliberal constitution. Understanding the limitations of the convention, how could redrafting the constitution fit with the wider anti-neoliberal and anti-capitalist struggle?

Camilo: I think it will be very difficult for anything to come out of the convention that can overcome the neoliberal nature of the constitution. It’s clear that the negotiated exit was designed not just to defend the regime, but also to defend the neoliberal system that was imposed on Chile by the Pinochet dictatorship.

In this sense, I don’t see how an exit designed to defend the regime can result in an alternative to the regime. This is why we believe that any change must come from below. It’s extremely important that the convention is influenced and accompanied by a process of permanent mobilisation. In the case that the expectations of the streets are not met, we must continue fighting, and continue pushing for a truly free and sovereign constituent assembly.

We understand that change never happens without a fight. They’re not going to give us anything. On the contrary, the ruling class clings to its privileges and defends the wealth that it has stolen from working people. So we know that to win change we have to organise, unite and fight. If we fight without mobilisations, and without working-class pressure against the interests of the millionaire minority that has kidnapped our democracy, there will be no substantial change.

Maura: Although the movement of the masses put up the slogan “It’s not 30 pesos, it’s 30 years”, which at first reads as being anti-neoliberal, the reality is that the demands for which we went into the streets only begin there. Actually, they go much deeper, questioning the structures of how this system produces and reproduces. What began in October 2019 is incipiently and unconsciously anti-capitalist, not just anti-neoliberal.

Additionally, the pact of 15 November, which the Frente Amplio signed, guaranteed that the fundamental pillars of the rentier and subsidiary state were maintained. Thus, we are not really even talking about a convention where we can debate anti-neoliberal features of the constitution, because the reality is that everything that has to do with the plunder and dispossession of the land will not be touched.

This is why we defend the need for a truly free and sovereign constituent assembly that is democratic and pluri-national. Any struggle for such an assembly will always be marked by the force of the mobilisations in the streets. So, the question for us is how, through intervening into this process where there is a significant politicisation of the masses, we can push for something new.