The death of Nelson Mandela closes the life of a heroic resistance figure who devoted his very being to the struggle against apartheid even though this came at immense personal cost. Mandela was, also, however, the saviour of South African capitalism, which condemned so many of his countrymen and women to continuing terrible hardship even after the destruction of the apartheid regime. His broad popularity in South Africa, ranging from the pauper to the plutocrat, cannot be understood without comprehension of both these facts.

Mandela was loved by the masses because of his immense dedication to and sacrifice for the cause, epitomised by the 27 years he spent in the regime’s rotten jails, 27 long years in which he grew to be an old man.

For the first 18 years of his imprisonment, Mandela was held on Robben Island off Cape Town, cut off from all that he had known. His first cell was a dank 2.4m by 2.1 m with only a straw mat to sleep on.

He was prevented from attending the funerals of his mother and first son, permitted only rare and brief visits by his daughters and wife Winnie, herself frequently jailed, beaten and banished for political activism. For the first decade he was allowed only one letter every six months. Newspapers were banned and prisoners were forbidden from talking to each other while eating or undertaking prison labour.

Prison life at Robben Island took its toll on Mandela’s health which makes his longevity all the more surprising. At the age of 46, he was condemned to hard labour on the island’s limestone quarry and denied sunglasses, the glare from the harsh sun ruining his eyesight. Many years later, at the age of 70, after having been moved to a jail in Cape Town, Mandela contracted tuberculosis.

Mandela could have won relief from all this by turning his back on the fight and on his comrades, by renouncing armed struggle, by cooperating with the apartheid system, by joining all those other black leaders who made peace with apartheid for 30 pieces of silver. But Mandela pursued instead the path of resistance for 40 years and, with other ANC activists, turned Robben Island into a university of struggle, forcing the prison authorities gradually to relax the harsh regime.

Before being thrown in jail, Mandela was, with a handful of others, responsible for reviving the rump African National Congress in the 1940s, a conservative organisation committed to the interests of the tribal leaders. The ANC’s vision went no further than sending fruitless appeals to London for redress. Mandela and his comrades transformed it into a mass organisation capable of mobilising thousands, and, later, hundreds of thousands of South Africans in a fight for freedom.

Mandela was instrumental in most of the turning points of the ANC’s modern history. With Walter Sisulu and Oliver Tambo, he created the ANC Youth League in 1944, which outflanked and then overturned the old leadership, ushering in a new generation of more militant leaders. The state repression of the 1950 May Day strike, which he opposed but which brought out half of Johannesburg’s black workers at the call of the Communist Party (SACP), brought home to him both the brutality of the state but also the realisation that the working class could be mobilised for political action and the need for better relations with the SACP, which he had previously fought vigorously.

Mandela was responsible for the 1952 Defiance Campaign, a movement of non-violent mass disobedience which helped the ANC’s membership balloon from 20,000 to 100,000. In 1955 he convened the Congress of the People, which hammered out the ANC’s defining statement, the Freedom Charter, and in the following year he was arrested with most of the ANC Executive for “high treason” against the state. The subsequent trial lasted six years. Mandela was found not guilty in 1961, but the jail doors were soon to slam shut on him.

Following the massacre of 69 protestors on the streets of Sharpeville in 1960, something that brought apartheid to the attention of the world, Mandela pressed ahead with plans to create an armed wing of the ANC and in 1961 formed Umkhonto we Sizwe ( MK) – Spear of the Nation – to carry out sabotage on military and civilian infrastructure within South Africa. If this failed, Mandela and his comrades planned to escalate the operation to guerrilla warfare.

At great personal risk, Mandela coordinated the MK sabotage campaign. However, he was quickly picked up by the authorities and in 1964 sentenced to jail for life, only narrowly beating the death sentence.

Although hostile to the left as a young man, a product of his own relatively privileged background and his early adherence to a narrow African nationalism, Mandela went on in the early 1950s to form an alliance with the SACP, in whose ranks were some of the country’s most committed trade unionists and socialists. This African nationalist-Communist alliance was to underpin the ANC’s trajectory in subsequent decades and explained its ability to win a mass audience among blacks.

The struggle of black South Africans inspired many millions of blacks around the world to fight for their rights. And not just blacks. For several generations of leftists, the anti-apartheid struggle was, with the fight against the Vietnam War, one of the main touchstones of all those involved in resistance to injustice. The image of Mandela languishing in jail was one of the most important elements of this struggle, personifying the sacrifices of so many nameless blacks who were similarly suffering the lash of apartheid. And when Mandela was released from jail in February 1990, the event was marked by celebrations around the world.

It is the memory of Mandela’s contribution to this struggle that is inspiring so many non-white and, indeed, many liberal white South Africans to express their collective grief at his passing.

Hypocrisy of the West

But it has not just been the masses who are expressing their sorrow at Mandela’s passing. Western statesmen and women are trying to outdo each other in their plaudits for the South African leader. British Tory Prime Minister David Cameron has called Mandela “a hero of our time” and ordered the flag at 10 Downing Street to be flown at half mast.

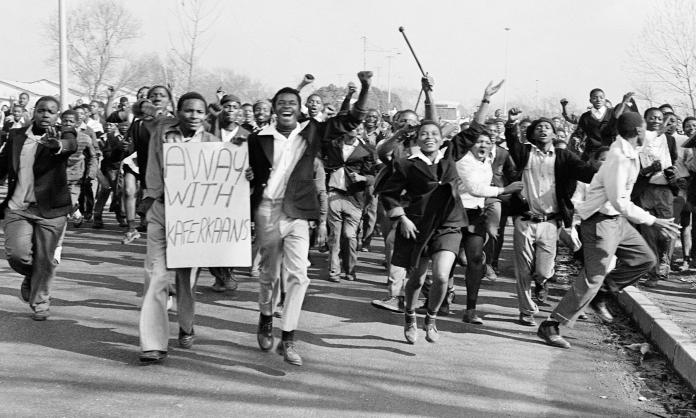

For those of us old enough to remember the heyday of the anti-apartheid struggle, these paeans of praise are nothing but a sick joke. As blacks were being shot in the streets, hanged on the gallows, jailed by the thousands, tortured in police cells and tear-gassed and clubbed while protesting in schools, universities, factories and mines, Western governments turned a cold shoulder to the South African fight for freedom and treated Mandela as a pariah.

So it was that when Mandela toured Europe in the early 1960s, looking for assistance for the anti-apartheid cause, the doors of pretty much every government were slammed in his face.

In the 1980s, both the Thatcher government and the Reagan administration in the United States routinely referred to the ANC as a terrorist organisation, and it took the US until 2008, 18 years after Mandela had been released from jail, before both he and the ANC were removed from its terrorism “watch list”.

Thatcher and Reagan were lavish in their praise of the Pretoria regime as a loyal Western ally. President Reagan told CBS in 1981 that he supported South Africa because “it was a country that has stood by us in every war we’ve ever fought, a country that, strategically, is essential to the free world in its production of minerals”.

These governments stood in staunch defence of the big Western capitalists who made a fortune from the cheap black labour whose perpetuation was the chief purpose of apartheid. Shell, Consolidated Goldfields, Caltex, Mobil, Honeywell, IBM, Ford, GM, Westinghouse, Pilkington, BP, Blue Circle and Cadbury Schweppes – a veritable Who’s Who of the London and New York stock exchanges – all invested heavily in South Africa in the 1960s, when the economy boomed. They maintained their investments through the 1970s even as the repression escalated. Others held shares in South African conglomerate Anglo-American, which made its enormous profits on the broken backs of South African mineworkers.

In the 1980s, a sustained divestment campaign forced some big companies to pull out, but not before they had licensed their products to local distributors. And the pull-out was done slowly and only patchily: at the end of 1987, 410 European and North American companies had divested from South Africa but 690 still remained. Even as late as 1988, US companies invested $1.3 billion in South African industry, and held $4 billion in investments, or 14 percent of the total, in the crucial mining industry. US exports to South Africa actually rose by 40 percent between 1985 and 1988. While there were profits to be made, Western businesses and governments turned a blind eye to the oppression of black South Africans.

The hosannas currently being showered on Mandela by these parasites are hypocrisy of the highest order.

Saviour of South African capitalism

So what explains this about-face by Western leaders? Why was Mandela transformed from communist stooge and terrorist to a secular saint and “Father of the Nation” in mainstream political discourse? Central to understanding this is his role in the transition from apartheid in the latter half of the 1980s.

Apartheid South Africa was hit by two major crises in the 1980s. For many years apartheid had been useful to international capitalism because, by savagely repressing the black working class, it kept wages sufficiently low to make the South African mining industry profitable. South African capitalism boomed in the postwar decades, with growth peaking at 8 percent in the first half of the 1970s. Thereafter the economy slumped and never recovered, with growth slowing down to a meagre 1.5 percent.

The economic crisis interacted with the explosion of popular insurgency, starting with the 1976 Soweto uprising and culminating in a nationwide wave of township insurrections in 1984-86. This insurgency meshed with the emergence of a black workers movement organised in largely non-racial unions. Starting in Durban in 1973 but reaching full force in the early 1980s, trade unionism swept the black working class. In 1979, the new unions were organised in a new union federation, FOSATU, whose leaders were in many cases revolutionary syndicalists who saw mass working class action as the vehicle to smash apartheid. Socialism gripped the unionised masses like a new gospel.

The administration of P.W. Botha initially responded to the economic crisis and upsurge of militancy by a combination of partial reforms and vicious repression. Botha hoped to extend the life of apartheid by incorporating Indians, so-called “coloureds” and a minority of blacks into the system. This project failed dismally when the ANC and its allies refused to cooperate. In 1986 Botha declared a state of emergency, an exercise in state repression but also an admission of failure. Nervous about “instability”, foreign capital started to flood out of the country.

The ANC could not be crushed by state repression. Even though the ANC had tailed behind, rather than led, many of the big developments of the period, such as the 1976 Soweto rising and the creation of the independent unions, it had nonetheless managed to attain hegemonic status within the movement. Rival currents, chiefly the Black Consciousness movement and the syndicalist unionists, failed to challenge it effectively, allowing it to take the initiative. This became clear in 1989 at the third congress of COSATU, successor to FOSATU, when the ANC’s political line of march dominated.

In this context, more far-sighted bosses in South Africa, along with an increasing number of foreign governments and business people, realised that the ANC had to be brought inside the tent and no longer shunned. All the epithets that the bosses had thrown at the ANC were forgotten when they realised that Mandela and the ANC were the only thing that could halt a working class revolution.

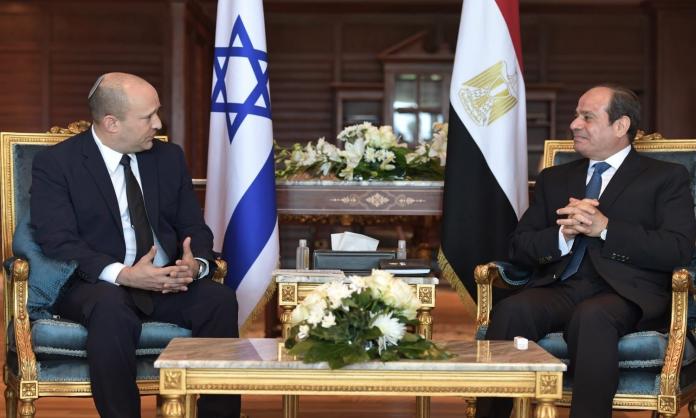

Starting in 1985 with a meeting in Zambia between ANC leaders in exile and South African business chiefs, the path to a negotiated removal of the apartheid political structure was therefore opened up. Restrictions on Mandela were gradually eased, and by 1988 he was regularly conversing with delegations of National Party ministers even while still a prisoner of the regime.

The ousting of Botha in August 1989 by F.W. de Klerk was another step in the reform project. De Klerk was a dyed in the wool National Party figure but could see that more radical concessions were needed. In February 1990 the new president freed Mandela and all other political prisoners and unbanned the ANC and SACP. Four years later, the ANC won a sweeping victory in the country’s first democratic elections. The political structures of apartheid were dismantled and black majority rule was confirmed.

It was during this period that Mandela became a darling of the West and hailed as saviour by his former enemies in South Africa. Mandela undertook all of the early negotiations alone and without consultation with his ANC comrades. He was the chief figure responsible for selling negotiations, in place of revolution, to the ANC’s mass base. At key moments in the transition it was Mandela who steered the masses away from an insurrectionary path towards set-piece stay-aways and demonstrations. So important was Mandela that the government was terrified when he contracted tuberculosis in 1988 – they feared that with his death there would be nothing to hold back the revolution.

The most important precondition for the negotiated settlement was that the fortunes of Anglo American and the other robber barons would be left untouched. Nationalisation was dropped from the ANC program, and Mandela repeatedly reiterated his commitment to private enterprise, foreign investment and “restructuring” of the big civil service and state-run industries that had been created by the National Party government.

The ANC leadership also agreed to leave the chain of command of the South African military and civil service intact and agreed to a five-year transitional “government of national unity” which was to include senior cabinet portfolios for National Party politicians.

In August 1990 Mandela ordered the cessation of armed struggle. While it may have been expedient given the ineffectiveness of this method against the continent’s most powerful military apparatus, this step signified a further willingness to accommodate.

Some ANC supporters condemned these moves as a sell-out. Many were angry at ending the armed struggle at a time when the government was unleashing death squads against ANC militants across the country. They confronted Mandela with placards “Mandela, give us arms” and “You are acting like a sheep while the people are dying”.

The conditions negotiated by Mandela were, however, entirely consistent with his long-standing politics. He had always supported private enterprise and a parliamentary set-up; his chief objection was that blacks were excluded from participating in them. At the Rivonia trial in 1964, Mandela told the court: “The ANC has never at any period of its history advocated a revolutionary change in the economic structure of the country, nor has it, to the best of my recollection, ever condemned capitalist society”.

The commitment to nationalisation contained in the 1955 Freedom Charter was only a token concession to appease working class delegates at the Congress of the People where it was adopted. It was never meant by Mandela to be treated seriously.

Neither Mandela nor the ANC nor even the SACP saw socialism on the agenda in South Africa. This was at best, for the SACP, something that awaited South Africa several decades after the supposed “first stage” of the revolution – the national democratic revolution – was completed. Nonetheless, the SACP was able to use its authority to defuse working class opposition to the rotten deal that was being negotiated in their name, with Mandela’s old MK comrade, the SACP’s chief theoretician Joe Slovo, at the forefront.

The ANC in office

Following the first democratic elections in April 1994, the black working class, which had struggled and suffered for the cause of socialism in South Africa, was left to drink a bitter brew by the ANC while the chiefs of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange, soon joined by a number of high profile ANC figures, continued to quaff champagne.

In their gratitude, the bosses cheered Mandela as the head of a new “Rainbow Nation” which enabled them to keep gouging big profits from the working class and shift their head offices overseas while blacks continued to suffer a life of shack housing, pit toilets, lack of running water, metered electricity, shoddy under-funded schools and Depression-era unemployment rates of 30 percent or more.

Two years after introducing a weakly reforming Reconstruction and Development Program, the ANC government abandoned even this in favour of the neoliberal Growth, Employment and Redistribution program, drawn straight from the World Bank recipe book. In 1995, Mandela won further praise from apartheid era die-hards by donning the shirt of the hated Springbok rugby team at the Rugby World Cup as he presented the trophy to the team captain. The wealthy citizens of Sandton, a virtually all-white posh suburb of Johannesburg, erected a statue in his honour at their local shopping centre.

This is why Mandela’s death is being marked today not just by those who dreamed that he would lead them to freedom but also by those bosses whose necks he saved when they came under mortal threat in the 1980s.With Mandela’s death we remember him both as a resistance leader but also as someone who sold his supporters short as he diverted their struggle into a capitalist dead-end.

The police murder of 44 striking platinum miners at Marikana in August last year, in scenes reminiscent of Sharpeville 50 years earlier, demonstrates that the struggle for genuine liberation of the South African working class still lies ahead. It will have to be done in opposition not just to the ANC but to the entire framework of nationalist politics on which Mandela’s life was based.

[Tom Bramble is co-editor, with Franco Barchiesi, of a book of essays about the South African working class titled Rethinking the Labour Movement in the “New South Africa”, which was published by Ashgate (Aldershot) in 2003.]

Public meeting:

Nelson Mandela – the Real Story about the Struggle against Apartheid

Tuesday 10 December, 6:30pm, Melbourne Trades Hall, 54 Victoria Street Carlton