When Nelson Mandela was freed from his Robben Island prison on 11 February 1991, my family, friends and neighbours followed the event with keen interest as they gathered in the living room of my old home in the Nuseirat Refugee Camp in the Gaza Strip.

This emotional event took place years before Mandela uttered his famous quote “our freedom is incomplete without the freedom of the Palestinians”. For us Palestinians Mandela did not need to reaffirm the South African people’s solidarity with Palestine by using these words or any other combination of words. We already knew. Emotions ran high on that day; tears were shed; supplications were made to Allah that Palestine, too, would be free soon. “Inshallah”, God willing, everyone in the room murmured with unprecedented optimism.

Though three decades have passed without that coveted freedom, something is finally changing as far as the Palestine liberation movement is concerned. A whole generation of Palestinian activists, who either grew up or were even born after Mandela’s release, was influenced by that significant moment: Mandela’s release and the start of the official dismantling of the racist, apartheid regime of South Africa.

Even the signing of the Oslo Accords in 1993 between Israel and some in the Palestinian leadership of the PLO—which served as a major disruption of the grassroots, people-oriented liberation movement in Palestine—did not completely end what eventually became a decided anti-Israeli apartheid struggle in Palestine. Oslo, the so-called peace process—and the disastrous “security coordination” between the Palestinian leadership, exemplified in the Palestinian Authority (PA), and Israel—resulted in derailed Palestinian energies, wasted time, deepened existing factional divides, and confused Palestinian supporters everywhere. However, it did not—though it tried—occupy every political space available for Palestinian expression and mobilisation.

With time and, in fact, soon after its formation in 1994, Palestinians began realising that the PA was not a platform for liberation, but a hindrance to it. A new generation of Palestinians is now attempting to articulate, or refashion, a new discourse for liberation that is based on inclusiveness, grassroots, community-based activism that is backed by a growing global solidarity movement.

The May events of last year—the mass protests throughout occupied Palestine and the subsequent Israeli war on Gaza—highlighted the role of Palestine’s youth who, through elaborate coordination, incessant campaigning and utilising of social media platforms, managed to present the Palestinian struggle in a new light—bereft of the archaic language of the PA and its ageing leaders. It also surpassed, in its collective thinking, the stifling and self-defeating emphasis on factions and self-serving ideologies.

And the world responded in kind. Despite a powerful Israeli propaganda machine, expensive hasbara campaigns and near-total support for Israel by the Western government and mainstream media alike, sympathy for Palestinians has reached an all-time high. For example, a major public opinion poll published by Gallup on 28 May 2021, revealed that “the percentages of Americans viewing (Palestine) favorably and saying they sympathize more with the Palestinians than the Israelis in the conflict inched up to all-time highs this year”.

Moreover, major international human rights organisations, including Israelis, began to finally recognise what their Palestinian colleagues have argued for decades:

“The Israeli regime implements laws, practices and state violence designed to cement the supremacy of one group—Jews—over another—Palestinians”, said B’tselem in January 2021.

“Laws, policies and statements by leading Israeli officials make plain that the objective of maintaining Jewish Israeli control over demographics, political power and land has long guided government policy”, said Human Rights Watch in April 2021.

“This system of apartheid has been built and maintained over decades by successive Israeli governments across all territories they have controlled, regardless of the political party in power at the time”, said Amnesty International on 1 February 2022.

Now that the human rights and legal foundation of recognising Israeli apartheid is finally falling into place, it is a matter of time before a critical mass of popular support for Palestine’s own anti-apartheid movement follows, pushing politicians everywhere, but especially in the West, to pressure Israel into ending its system of racial discrimination.

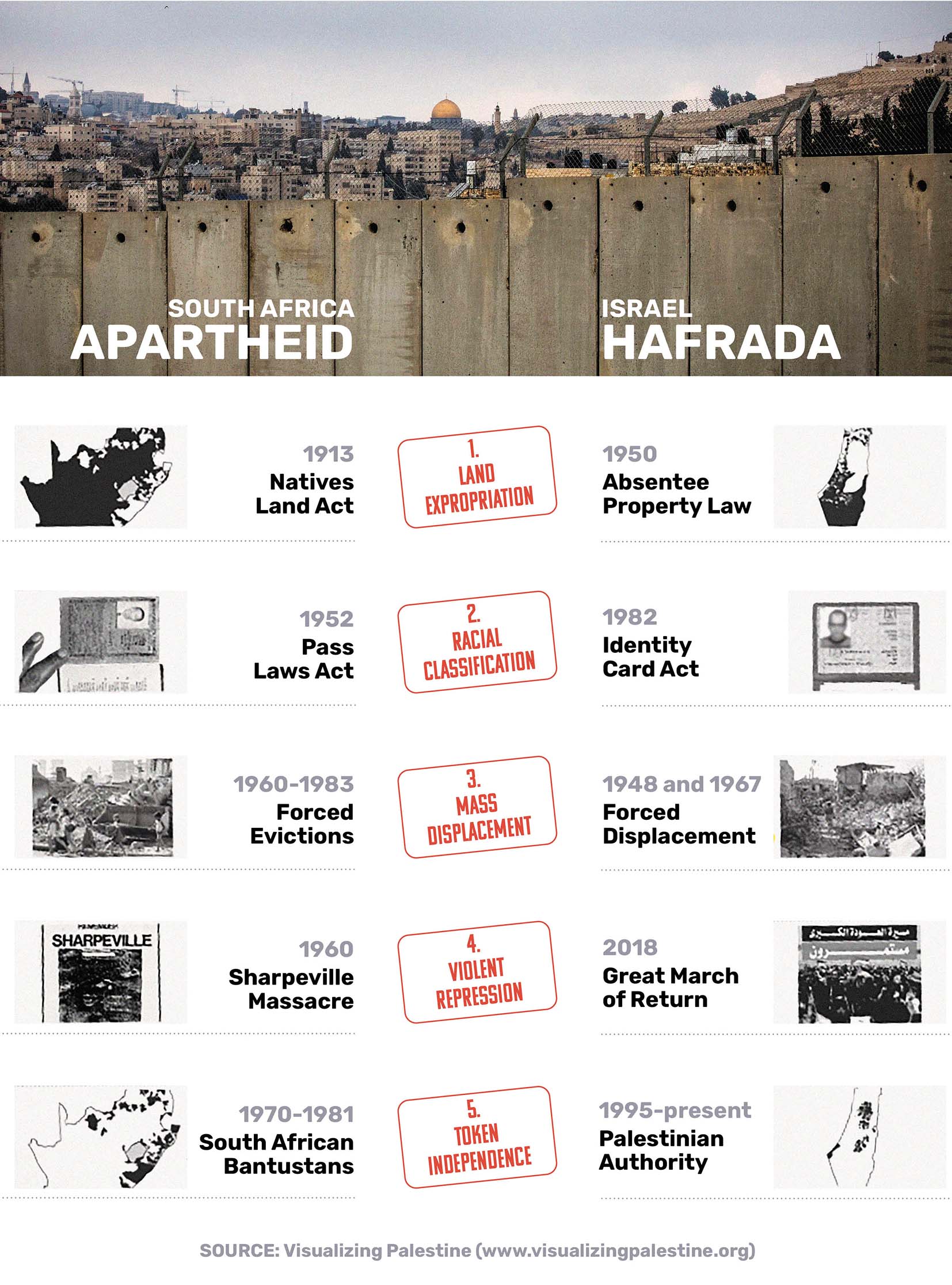

However, this is where the South Africa and Palestine models begin to differ. Though Western colonialism has plagued South Africa as early as the seventeenth century, apartheid in that country only became official in 1948, the very year that Israel was established on the ruins of historic Palestine.

While South African resistance to colonialism and apartheid has gone through numerous and overwhelming challenges, there was an element of unity that made it nearly impossible for the apartheid regime to conquer all political forces in that country, even after the banning, in 1960, of the African National Congress (ANC) and the subsequent imprisonment of Mandela in 1962. While South Africans continued to rally behind the ANC, another front of popular resistance, the United Democratic Front, emerged, in the early 1980s to fulfil several important roles, among them the building of international solidarity around the country’s anti-apartheid struggle.

The blood of 176 protesters at the Soweto township and thousands more was the fuel that made freedom, the dismantling of apartheid and the freedom of Mandela and his comrades possible.

For Palestinians, however, the reality is quite different. While Palestinians are embarking on a new stage of their anti-apartheid struggle, it must be said that the PA, which has openly collaborated with Israel, cannot possibly be a vehicle for liberation. Palestinians, especially the youth, who have not been corrupted by the decades-long system of nepotism and favouritism enshrined by the PA, must know this well.

Rationally, Palestinians cannot stage a sustained anti-apartheid campaign when the PA is allowed to serve the role of being Palestine’s representative, while still benefiting from the perks and financial rewards associated with the Israeli occupation.

Meanwhile, it is also not possible for Palestinians to mount a popular movement in complete independence from the PA, Palestine’s largest employer, whose US-trained security forces keep watch on every street corner that falls within the PA-administered areas in the West Bank.

As they move forward, Palestinians must truly study the South African experience, not merely in terms of historical parallels and symbolism, but to deeply probe its successes, shortcomings and fault lines. Most importantly, Palestinians must also reflect on the unavoidable truth—that those who have normalised and profited from the Israeli occupation and apartheid cannot possibly be the ones who will bring freedom and justice to Palestine.

First published at ramzybaroud.net. Ramzy Baroud is a journalist and the editor of the Palestine Chronicle. His latest book, co-edited with Ilan Pappé, is Our Vision for Liberation: Engaged Palestinian Leaders and Intellectuals Speak