It was 1961. Migrants erected a sign on the roadside twenty kilometres outside of Albury: “Bonegilla, Place of No Hope”. The authorities left it there, perhaps for fear of further inflaming the bitterness that inspired it.

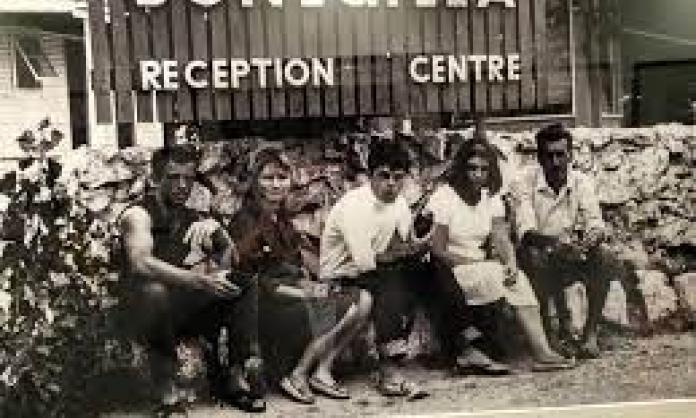

Bonegilla was a reception and training centre for immigrants. They were supposed to learn English and be found a job, neither of which turned out to be guaranteed. Indentured for two years, they were obliged to take whatever jobs the government sent them to.

After World War Two, there were 8.5 million war refugees around Europe, euphemistically labelled displaced persons (DPs) by the United Nations. The Australian administrator of the UN rehabilitation scheme in 1944-48 shamefully referred to them as “the flotsam and jetsam of the war”.

Between 1947 and 1951, most migrant arrivals to Australia were refugees. Preference was given to British and northern Europeans, considered more white than southern Europeans.

Bonegilla’s capacity was expanded from about 1,500 in 1947 to 7,700 by 1950. In “emergencies”, such as recessions or the 1949 coal strike, which meant periods of fewer jobs, overcrowding was the norm.

Approximately 320,000 people from 35 different ethnic backgrounds passed through Bonegilla, the longest running of 50 such centres. It closed in 1971.

Its management regime was driven by a bureaucratic mentality that regarded immigrants as mere chattels, a view cultivated by official attitudes and government policy.

Chifley, the Labor prime minister, summed up the racist fears of the ruling class in his slogan “Populate or Perish!”

Glenda Sluga, in her history of Bonegilla, argues that public proclamations “reinforced not only the illusion and practice of ‘control’, but the assumption that it was ... necessary”. For example, Arthur Calwell, the minister for information, informed the public in November 1947: “We shall have to select them [the migrants] because ... We do not want traitors and collaborators”.

They were thoroughly vetted to ensure that they were strong and healthy and with no communist sympathies. And it was clear that they were destined to do dirty, soul-destroying jobs for wages Australian-born people would not accept.

Bonegilla was a former army camp used to incarcerate prisoners of war. Spartan and dilapidated, accommodation was timber, tin-roofed and unlined huts. Wide gaps in the walls provided ventilation but no protection from mosquitoes, flies, the winter cold or the dust storms.

Crammed into huts with no partitioning, all meals served in the canteen with no choice, the interned were stripped of dignity.

Those billeted at the perimeter had a three-kilometre walk to the administrative centre. Personnel from the Department of Immigration described it as “very dirty and poorly equipped”.

As Sluga comments: “No one had ever pictured the lucky country in the shape of tin army huts and barbed wire compounds”.

Oral accounts capture the careless lack of empathy of those in authority over them.

Augustus, an Austrian, determined to make the most of this new life, tells of having their belongings searched when their suitcases arrived:

“Books were in there he ran through the pages and out came a branch of Oak and a blue flower [carefully preserved in his last hours in Europe]. He took them and tossed them into a sort of incinerator. I was ready to blow ... That young Ostralian officer could NOT know what he did to me.”

Nina, a well-educated German from a comfortable background, recounted her arrival with her husband:

“Men all on this side, women all that side. Some people panicked because they had heard [at] concentration camp too, men one side, women other side ... We were just like cattle, here follow us—men were more than one kilometre away. We were not told. We were just treated like stupid sheep.”

Sluga sums up the accounts she recorded as “resigned disappointment, and often bitter bewilderment”.

The family, that sacred bedrock of the Australian Way of Life, was brutally disregarded. Sons and daughters over 16 were subject to employment directions.

Young women were generally sent to canneries, clothing factories or as “mother’s helpers”, nurses’ aides and the like. One family’s daughter was sent to Sydney, the mother and younger daughter to a Cowra Holding Centre for women and children while the father and son worked all around NSW.

Estonians Marta and her elderly mother had spent five years in refugee camps. Her mother spent years in Cowra before being returned to Bonegilla as “mother’s helper” for Marta, who now had children.

Names could peremptorily be “Australianised”. Even getting married gave officials control over them. Writing to the migration official about Marta and Thomas’ application for permission to marry, the camp manager wrote: “John ... should eventually make a considerable [sic] better than average citizen”. Of “Margaret”, he opined, “I am quite satisfied that she will eventually prove a good Australian”.

However, this authoritarian oppression provoked protests.

In 1950, women at the Cowra Holding Centre raised a black flag, indicating mutiny against their children’s rations. There was no press comment or official reaction. In Bonegilla, Catholic priest, Father Collins, complained about the treatment of men who had staged a hunger strike and refused to obey orders.

Dismissed by the manager as “meddling”, his dogged defence of his followers led to a number of investigations. One concluded that “the rule of intimidation” was the norm. Migrants employed at the camp who joined a union were threatened with the sack if they maintained contact with it.

Between October 1951 and June 1952, 5,325 voluntary Italian migrants arrived. Having paid half their fare, and tenured for two years, they expected the government would honour its commitment to find them jobs. But recession left them languishing with no employment and no explanation of why.

Guards appointed by the manager, a Sergeant Dawson, (which were actually illegal) policed their “morals”—for example, enforcing the separation of men and women. They were denied newspapers; even English classes were far and few between. Several told Sluga that you could learn virtually any language—but not English!

In April 1952, a hut was inexplicably burned down. Men started sitting on the railway tracks to stop trains that could take them to Melbourne. Then in July, 2,500 signed a protest petition, and the Border Morning Mail informed the Albury population that a riot was threatened.

An army convoy of 200 fully armed troops were involved in “exercises” on the perimeter, and the press was banned from the camp. About 2,000, mostly Italians, gathered to protest. As they marched to the main office, imagine their terror when four tanks bearing machine guns on top bore down on them.

Eros recalled that there “was no work for anybody. Somebody start to get mad and they start to throw stones at the main building”.

Giovanni says they asked for jobs or to be sent back to Italy. When the manager said he had no authority to do either, they “started to revolt”.

“We burned two or three huts and set fire to the church”, he related. Not because of hostility to the church. They were just fed up with being told to “have patience, God is on your side”.

“We had no intention really to burn anything, we just wanted to show ... [that] we mean business.”

Later, the Italian consul addressed them: “You are fortunate to be in a country like Australia”. Giovanni said:

“People rush on the stage and nearly killed him. His car burned, the hall ... was destroyed. The police had to ... rescue him through the back door. And that was the Bonegilla revolt of 1952.”

Speculation as to what happened was rife, but no-one bothered to investigate the reasons for the rebellion. Discontents were just dismissed as coming from “outsiders”, or “communist agitators”; protests were put down to the “Italian propensity to demonstrate”.

Dawson, notorious for sanctioning violence by the guards to maintain “order”, called for ASIO to be brought in, for a permanent police presence and for deportations.

But they showed that protest works. Italians were brought in to cook real pasta, replacing the tinned mush they were served. They got olive oil and tomato paste, and some leisure facilities were gradually constructed.

Eros, one of a delegation to Immigration Minister Holt, warned him that he could have a “revolution” on his hands. By the time they returned to Bonegilla, three-quarters of the migrants had been sent to other camps.

In the next seven months, 5,300 Italians were placed in “emergency” work. But Dawson reported ongoing demonstrations “by wildly gesticulating and table thumping Italians, who ... desired to dictate the policy ... in allocating them to employment”.

Voluntary migrants had higher expectations of good jobs than DPs. But they were given jobs that fitted the demands of employers and government, not their aspirations.

In September 1952, the DPs (who Dawson regarded as model migrants) staged a protest. But it was successfully kept out of the press, and the Central Employment Office dismissed their demands: “It is felt that they are better off in Bonegilla than they would have been ... in Displaced Persons’ camps in Europe”.

Militant protests tend to inspire others. In the following months, protests over similar issues occurred at Maribyrnong hostel, Sydney Central Station, Villawood hostel and Matraville.

A new administrator at Bonegilla in 1954, Colonel Henry Guinn, was appalled at the conditions. A cinema and other facilities provided some diversion, 13,000 trees were planted, and more gender and national equality was observed.

In the late 1950s, some remained for years in camp jobs, denied the opportunity to take control over their lives.

And so to the day, nine years later, in 1961, they erected the sign on the road: “Bonegilla, Place of No hope”. Protesters carried what were said to be “ugly signs” such as “We want work” and “Your barbaric system only worthy of the stone age”. Perhaps the ones in Greek lettering were the ugly ones.

Il Globo, a Melbourne Italian-language newspaper, described how dozens of police pouring into the camp provoked a “second wave of disorder”.

The night after the protest, police rampaged in family huts, breaking the arm of one man who had only days before had surgery. The migrants built barricades from cans, boxes and empty bottles.

Over two days, buildings were damaged and windows smashed. Local and government officials blamed Italians and communists.

The complaints echoed those in 1952: appalling food and facilities, and that they had been enticed to Australia by false promises of good jobs and a better life.

In response to a media barrage of verbal abuse, the Italians, while being a small minority of protesters, proudly acknowledged their leading role and proclaimed that they did not regret anything. Within a few short years, Italian workers would play a prominent, militant role in strikes in the car plants of Ford and GMH.

Trying to hush up the discontent, and playing on Cold War hysteria, ASIO was brought in and threats of deportation were made.

Nevertheless, again the protests won improvements. Many were relocated to urban centres where it was more likely they could find work.

These protests in the face of inhuman authoritarianism, behind barbed wire, isolated from potential supporters, should be better known. They are part of the history of workers’ struggles in this racist country.

They challenge the myths and lies of the official heart-warming narrative of migrants seamlessly assimilating into a welcoming nation.