Burkina Faso, a small landlocked country in West Africa, has been rocked by mass protests, the trashing of the parliament and the resignation of president Blaise Compaoré. The military has stepped in, naming high-ranking officer Isaac Zida as the country’s interim leader.

But opposition and protest leaders swiftly issued a statement demanding a “democratic and civilian transition”.

“In no case can [power] be confiscated by the army,” they said. They also called for a mass rally in the capital, Ouagadougou, at the site now known as “Revolution Square”, where up to a million people had previously gathered to demand Compaoré’s resignation. The following piece was written by journalist Siddhartha Mitter as events were unfolding on 31 October. It was first published at Africaisacountry.com.

----------

At the moment of writing this post – October 31, late afternoon – the leader of Burkina Faso may be general Honoré Traoré, the army chief of staff, who declared himself president yesterday. It may, instead, be lieutenant colonel Isaac Zida, second-in-command of the presidential security regiment, who has just announced the closure of the borders.

By the time you read this post, it is possible that retired general Kwamé Lougué, who was sacked as defence minister in 2003, and whom many protestors and opposition figures appear to trust, will have emerged as leader instead – or some other character yet to be named. The power struggle clearly involves factions of the military with very different interests and degrees of intimacy with the regime of former president Blaise Compaoré, who resigned this morning and has taken refuge in Ghana, and how it will be solved – through negotiation, bloodshed, or otherwise – is the question of the hour.

On Radio Omega, the private news station in the capital Ouagadougou whose internet feed has been invaluable for following this crisis from afar, the host and guests, right now, are engaged in a detailed but somewhat theoretical discussion of the mechanics of a political transition period that one cannot yet be sure has begun. The emphasis is on rules and constitutional arcana: what new texts must be written, who should write them, how should the process be supervised?

The speakers are digging into the procedural concerns that take up so much discussion, and occult so many concrete issues, in Francophone Africa. A member of parliament is on the line, saying that as far as he is concerned, the dissolution of the national assembly, announced yesterday, is not of legal effect. Then a surprise call from a top political figure: the head of the opposition, Zéphirin Diabré, with an urgent appeal for protesters to stop looting and damaging property. The host tries to draw him out: “Are you in touch at the moment with the military?” Diabré says he can’t talk about that right now, and quickly hangs up.

As the top of the hour nears, the host asks his guests, point blank: “So who do you think is currently head of state?”

There is a beat, followed by the audible equivalent of a chorus of Gallic shrugs. “Well,” one says, “I’m guessing it’s the chief of staff, and this colonel is acting as spokesman.”

“But the wording of his communiqué makes no mention of the chief of staff, and the way he signs it, in the name of the forces of the nation, makes it sound …”

“True. Perhaps he’s taking over.”

“So would that be a takeover in constitutional terms, or in military terms?”

“Probably in military terms. No one’s talking about the constitution.”

“So it’s a coup within a coup?”

“Let’s call it a coup within an uprising.”

Everyone chuckles, and the show ends. The music break is conscious hip-hop in French, with a live balafon. After a public service announcement about keeping Ouagadougou’s streets clean, and then some ads, a reggae track comes on. Its chorus is the revolutionary slogan that captain Thomas Sankara installed during his three years of inspirational rule, before his friend and deputy, Compaoré, killed him in 1987: “La patrie ou la mort, nous vaincrons” (“Fatherland or death, we shall overcome”). The slogan has been all over the streets of Ouagadougou and Bobo-Dioulasso (the country’s second largest city) these last few days of mass protest, ushering Compaoré out after 27 years of reign.

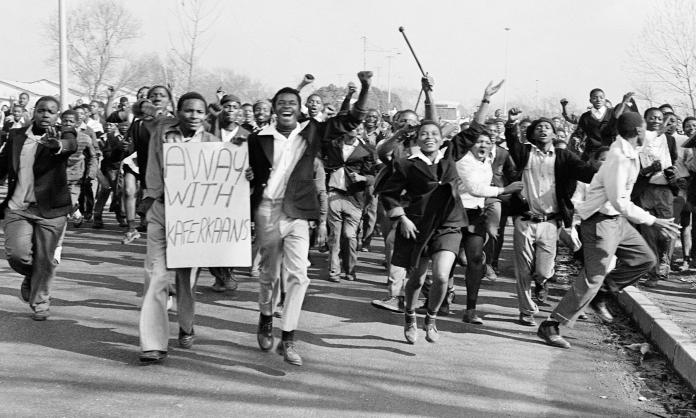

Everyone loves a good popular uprising, especially one that unseats one of Africa’s more dinosaur-like presidents, who was in office much longer than most of his people have been alive – Burkina Faso’s median age is 17 – and who wanted to cling on by forcing through a constitutional amendment that would let him contest yet another term. That classic technique doesn’t wash the way it used to. Thomas Sankara remains a hallowed pan-African figure, too, and to see people power in Burkina Faso overthrowing, at last, the Brutus figure who ended his experiment in liberation politics is a stirring image.

The surprise effect can’t be overlooked either: really, it is only the Burkinabè people and a small number of outside friends and observers who had any sense of the momentousness of these protests. Distracted and overstretched by the Ebola outbreak and the Boko Haram crisis, very few international outlets had reporters in Ouaga for the events, and reporters trying to hurry there now are apparently having trouble getting visas.

One who was there, the Reuters photojournalist Joe Penney, has filed a series of images that not only show the massive scale of the demonstrations and the customary confrontation of protesters and riot troops, but also capture a bit of this romance. One is an instant-icon image of protesters in motley gear – military berets, button-downs, one guy bare-chested holding up a set of speakers, another giving the finger, and one in a classic Public Enemy T-shirt – posing on the set at the just-taken-over state television headquarters.

Beyond the sheer effervescence and punk-rock energy of the scene, it’s also a brilliant pastiche of the familiar coup image, where too many soldiers crowd into the frame while one of them reads out a ponderous communiqué suspending the constitution and civil liberties in the higher interest of the nation. But a few hours later, it was precisely such a scene that unfolded at army headquarters, as the declaration naming general Traoré president was read. The six hours or so between those two moments, in the afternoon of October 30, signalled – even as an #AfricanSpring hashtag began to float in social media – the Burkina Faso uprising’s inevitable tilt from romance to Realpolitik.

What happens now? By the time you read this, the plates will have likely shifted again. But there are several classic scenarios, all of which, for now, seem to point toward a military-run transition of some kind. Constitutionally, the speaker of parliament is supposed to take over in the event of “vacancy of power,” but the constitution seems to be out the window.

A high-stakes negotiation is almost certainly underway among military factions that harbour deep resentments toward one another and an opposition that will struggle to stay united. It is very likely that presidents of neighbouring countries, such as John Dramani Mahama of Ghana and especially Alassane Ouattara of Côte d’Ivoire, whose camp has many close ties in the Burkinabè elite and military, are weighing in discreetly. The involvement of the French and American ambassadors is a given.

In the last decade, Burkina Faso has become a central node in the new security apparatus that France and the US are building, separately but in coordination, in the Sahel region, to combat jihadi movements and buttress their other interests. Ouagadougou is a base for US drones as well as French special forces. As fluid as the current situation may be, nothing in the power struggle underway appears to threaten Burkina Faso’s fundamental alignment with France and the US, and both powers are likely actively working to shape an outcome they can work with.

In recent weeks, France had already signalled readiness to see Compaoré exit the scene (a letter from François Hollande promised Compaoré French support should he seek to exercise his talents in some international organisation); reporter Nicolas Germain of France 24 told me on Twitter that French diplomatic sources had commented to him that Burkina, “unlike some countries, has a credible opposition”. As Germain commented: “That says everything”.

There is no need to temper the genuine joy, in Burkina Faso, that Blaise Compaoré is no longer head of state. But hope for a more radical kind of upheaval, of a progressive and pan-African nature, is likely to be dashed. And the grassroots activists of Ouaga and Bobo, who have chosen as emblems the broom and the wooden spatula used to prepare the millet dish tô, know that their chores in the national household are far from over.