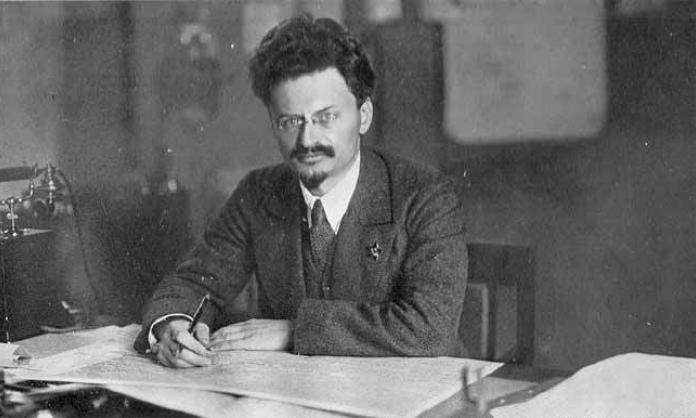

“Either the Russian revolution will raise the whirlwind of struggle in the West, or the capitalists of all countries will crush our revolution.” It was 25 October 1917, and Trotsky was addressing the delegates of the Second All Russia Congress of Soviets in Petrograd (formerly Saint Petersburg). Earlier that day, he had helped organise and lead the first successful workers’ insurrection.

Trotsky’s assessment would be vindicated over the coming years. The mass revulsion at the horrors of World War One, combined with the inspiration of the Russian Revolution, ignited a six-year wave of revolt that spread across Europe. And within days of the October revolution, the Whites—former Russian generals, landlords and capitalists backed by governments across the world—began subjecting the new workers’ state to counter-revolutionary terrorist violence and war.

The workers’ Red Army, led by Trotsky, ultimately defeated the Whites. But the civil war ruined the already feeble Russian economy and decimated the working class. Hundreds of thousands of militant Bolshevik workers had joined the Red Army; many of them perished. Tens of thousands became officials within the administration of the new state.

In all the old Bolshevik strongholds, militant workers were replaced by peasants from the countryside who had none of the traditions of class struggle and socialism. The number of industrial workers declined by more than half. Manufacturing collapsed. The institutions through which workers had taken power—the soviets—were reduced to empty shells.

The Bolshevik (renamed Communist) Party was forced to substitute itself for the decimated working class. This led to the increasing fusion of state and party and the centralisation of decision making in the party itself. It also led to the suppression of other political organisations that had joined the side of the counter-revolution. The result was a Bolshevik monopoly on political power. These extreme measures reflected what was at stake: the alternative was to give up and hand power to the Whites. Trotsky commented at the time that if Bolsheviks had done this, “fascism” would have been a Russian word.

The end of the civil war brought the regime new problems. Now that the peasantry had been granted their main demand, the redistribution of land, they had little interest in the collective struggle for socialism. Peasant revolts—the most famous taking place in Kronstadt—signified that a political retreat was necessary to keep the peasantry on side while the regime held out for a successful workers’ revolution in an industrially developed country such as Germany.

In 1921, the New Economic Policy reintroduced elements of the market into the economy. The result was another shift in the balance of class forces: a new class of capitalist farmers emerged from the ranks of the peasantry along with a layer of urban capitalists.

The impact of the civil war and the isolation of the revolution led to the rise of a new state bureaucracy. The Bolsheviks were compelled to integrate functionaries from the old regime into the new state apparatus during the war. Initially, they could be disciplined by the revolutionary movement, but as it ebbed, the bureaucracy began to develop a will of its own.

Bolshevik Party members such as Joseph Stalin—who had made no useful theoretical contributions to Marxism, played no notable role in the October Revolution and had been wrong in all the major party debates in 1917—rose to prominence in the authoritarian environment of the bureaucracy. If political leaders express the needs of different classes in their struggle for power, then the bureaucracy found its leading figure in Stalin.

The Bolsheviks assumed that if counter-revolution emerged victorious, it would do so through conquest by foreign armies or by the restoration of the old ruling class. No-one envisaged that it would take place through the bureaucratised Bolshevik Party itself.

Trotsky became the leading figure in the struggle against the bureaucracy. In 1923, he led what became known as the Left Opposition, which took up the fight, initiated by Lenin in the last months of his life, to democratise the party and revive the soviets as genuine institutions of workers’ democracy.

In response, Bolshevik leaders Stalin, Zinoviev and Bukharin (known as the troika) launched a hysterical campaign against “Trotskyism”. “All the old formulae of Bolshevism were named ‘Trotskyist’”, Trotsky later commented. “The genuine thing in Bolshevism is opposed to every privilege, to the oppression of the majority by the minority. It was named ‘the program of Trotskyism’. That was the beginning of the frame up.”

The troika relaxed the rules governing party membership, opening the organisation to hundreds of thousands of careerists who viewed membership as a ticket to personal advancement. They consolidated the control of the Russian party over the Comintern (the international organisation of communist parties). “The attitude towards Lenin as a revolutionary leader gave way to an attitude like that towards the head of an ecclesiastical hierarchy”, wrote Trotsky. The troika was able to defeat the Left Opposition politically through their control over the party apparatus. Their victory was assured when the post-WWI revolutionary wave that had swept Europe finally ended with the defeat of German workers in 1923.

If Trotsky and his supporters were to defeat the bureaucracy, they would need a revolutionary upsurge of the working class. But the working class inside Russia was exhausted after years of war and famine.

The 1926 general strike in Britain and the Chinese revolution of 1925-27 led to an upsurge of oppositional activity inside Russia (now organised as the United Opposition, Zinoviev having joined Trotsky) and presented an opportunity to put workers’ struggle back on the agenda in Europe and Asia. But each opportunity was sabotaged by the class-collaborationist policies of the Comintern, which now promoted the bureaucratic interests of the apparatus in Moscow through the various international communist parties.

These defeats helped consolidate the bureaucracy against the United Opposition which, at the end of 1927, was expelled from the party. Trotsky was exiled first to Alma Ata in Kazakhstan, then to Turkey, Norway, France and, finally, to Mexico.

The horrors of Stalinism in the USSR proceeded apace. Forced collectivisation of peasant land and rapid industrialisation at the expense of consumption led to the deaths of millions. Show trials led to the murder of the surviving revolution-era Bolsheviks and their replacement with a new generation of bureaucrats moulded by Stalin’s regime.

“The present purge draws between Bolshevism and Stalinism not only a bloody line but a whole river of blood”, Trotsky wrote in 1936, at the height of the purges. “The elimination of the entire old generation of Bolsheviks, an important part of the middle generation, which participated in the civil war, and that part of the youth which took seriously the Bolshevik traditions, shows not only a political but a thoroughly physical incompatibility between Bolshevism and Stalinism.”

Nevertheless, thousands of new “Trotskyists” (who identified the label with opposition to the regime) continued to organise and resist from inside Stalin’s dictatorship.

In 1936, Trotskyist prisoners at the Vorkuta forced labour camp organised a hunger strike that lasted 132 days. One report described “a group of nearly a hundred, composed mainly of Trotskyists” being led away to be shot. “As they marched away, the condemned sang the ‘Internationale’, joined by the voices of hundreds of prisoners remaining in the camp.”

Stalin also took revenge on Trotsky’s family. Of his four children, two were executed in the gulags, one was driven to suicide in Berlin and another was murdered by Stalin’s agents in Paris. In his obituary for his son, “Leon Sedov—Son, Friend, Fighter”, Trotsky summed up the scale of the defeat: “That which tsarist hard-labour prisons and harsh exiles, the hardships of emigration, the civil war and disease had failed to accomplish has in recent years been achieved by Stalin”.

Despite these defeats, Trotsky fought to keep the tradition of genuine Bolshevism alive. His History of the Russian Revolution, published in 1930, upheld the memory and lessons of the October Revolution just as they were being buried by the Stalinist bureaucracy.

Trotsky continued to organise the opposition internationally. His writings on the rise of fascism in Germany, the revolutionary wave of May-June 1936 in France and the Spanish civil war of 1936-39 put forward a clear line of action for the working-class movement. Despite the correctness of Trotsky’s analysis, however, his supporters remained small and isolated—vastly outnumbered by the forces of reformism and Stalinism—and were unable to translate Trotsky’s ideas into mass action.

It was during this period that Trotsky wrote his analysis of the USSR, The Revolution Betrayed. Published in 1937, the book refuted Stalin’s claim that Russia had achieved socialism. Trotsky demonstrated how in every aspect of life—work, family, gender and sexual relations, politics, education, health care—the oppression of Russian workers continued. The state apparatus, instead of withering away, had grown into a monstrosity towering over the masses. “With the utmost stretch of fancy it would be difficult to imagine a contrast more striking than that which exists between the schema of the workers’ state according to Marx, Engels and Lenin, and the actual state now headed by Stalin”, he wrote.

Trotsky believed that the Stalinist bureaucracy was highly unstable and would collapse under the pressure of the World War Two. But the USSR emerged from the war strengthened, setting up a series of satellite states in Eastern Europe. Trotsky also argued that the world capitalist system was in an intractable crisis that would lead to revolutionary struggles. Instead, capitalism entered a long period of growth and relative stability.

Trotsky did not live to participate in the political debates that followed the war. In his obituary on Trotsky, Victor Serge, an anarchist who had been won to Bolshevism during the Russian Revolution and later became a member of the Opposition, reflected on his comrade’s legacy:

“I have never known him greater, and I have never held him dearer, than I did in the shabby Leningrad and Moscow tenements where, on several occasions, I heard him speak for hours to win over a handful of factory workers, and this well after he had become one of the two unchallenged leaders of the victorious revolution. He was still a member of the Politbureau but he knew he was about to fall from power and also, very likely, to lose his life. He thought the time had come to win hearts and consciences one by one—as had been done before, during the tsar’s rule.

“Thirty or forty poor people’s faces would be turned towards him, listening, and I remember a woman sitting on the floor asking him questions and weighing up his answers. This was in 1927. We knew we stood a greater chance of losing than of winning. But, still, our struggle was worthwhile: if we had not fought and gone under bravely, the defeat of the revolution would have been a hundred times more disastrous.”