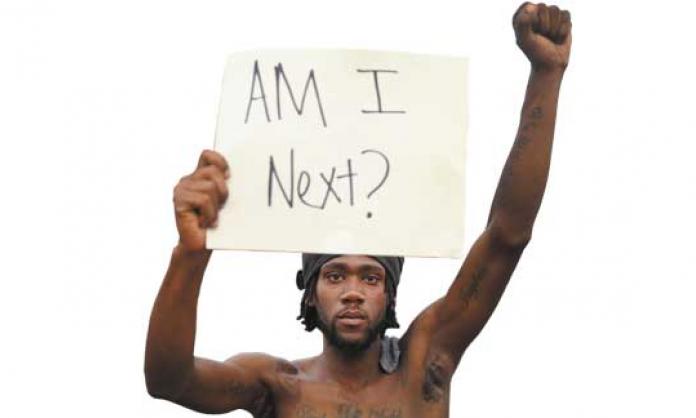

The struggles against police murders of African Americans (mainly men) have spread nationally since the events in Ferguson, Missouri, last August.

A nascent movement of Black people is being formed, with young people in the vanguard.

A racist backlash centring on defence of the police has also developed, which has significant support in the ruling class. A political struggle between these two opposed forces will take place in the next period. One side is defending the status quo, and the other side is fighting for justice and to end cop violence. It is likely that some of these new leaders will come to see their struggle as part of a wider fight against the whole system. Police killings are not new. A recent study has estimated that such incidents occur somewhere in the country every 28 hours. But the eruption of protests in Ferguson in response to the police murder of Michael Brown marked something new.

There had been protests against police violence against young Blacks before, such as the case of Oscar Grant in Oakland, California, in 2009, and the murder of Trayvon Martin in Florida by a police-connected vigilante in 2012.

But the sustained protests in Ferguson and the militarised police response reverberated throughout the country with sympathy demonstrations. The issue of police killings of Black youth became part of a national discussion.

Protests have made the slogans “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot!” and “No Justice, No Peace!” well known. Recent protests have popularised “Black Lives Matter”, which echoes the Black Power demands of the 1960s that were proactive, not only defensive.

In October, there were renewed mass actions in Ferguson and the St. Louis region (Ferguson is a suburb of that city). It became clear that these actions were organised by African American youth in Ferguson.

These new leaders came out of the original Ferguson protests in August. But after those initial protests died down, these young people did not become inactive, but the opposite. They began to organise groups of young leaders, and to lay plans for the October actions.

While many protests were called in response to similar killings in cities across the country, one incident stood out: the 3 December decision by a grand jury not to indict police for strangling to death Eric Garner, a 43-year-old Black man, in New York City earlier in the year.

Protests erupted, culminating in a march of 30,000 on 13 December. This was part of a national day of protests against police murders of Blacks.

Some 10,000 marched on the White House in Washington, led by reverend Al Sharpton’s National Action Network (NAN).

Breaking with the establishment

One incident at the Washington march was indicative: people in the crowd began demanding that young leaders from Ferguson be allowed to speak – they were not on the official speakers’ list. A scuffle ensued, and NAN marshals initially prevented them from speaking. Finally, one young leader from Ferguson was allowed to speak, defusing the embarrassing confrontation.

The young Black women and men who have come to the fore in many of these actions have taken steps to bring in the established Black organisations and leaders when possible.

At the same time, it is clear that this new layer of leaders refuses to be told what to do by the Black establishment, which is tied to the Democratic Party. “Sharpton doesn’t speak for us”, commented one of these young leaders.

Sharpton has spoken out on this issue and organised actions more than any other person in the Black establishment, putting him head and shoulders above them. At the same time, his objective is to try to keep this new movement within the confines of the Democratic Party.

Observing the protests, another thing has become apparent: young white people, not just the familiar white radicals, are joining them.

Racist backlash

From the beginning of this new wave of protests, there has been a racist backlash, evident in the right wing media and in the refusal to indict the killer cops.

Spearheading this new phase of the reactionary counter-movement are the police and district attorneys. This was seen in Ferguson from day one, police wearing on their uniforms “I am Darren Wilson”, the white cop who murdered Michael Brown.

St. Louis cops demanded that Black football players for the St. Louis Rams be disciplined for coming out on the field with their hands up, in the “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot!” gesture that has become ubiquitous in the protests.

The backlash gained momentum at the end of December when two New York cops were shot by a Black man. Patrick Lynch, the head of the New York Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, went on the offensive. He blamed the new protest movement for the murders: “There is blood on many hands, from those that incited violence under the guise of protest to try to tear down what police officers did every day.

“That blood on the hands starts on the steps of city hall in the office of the mayor.”

The attack on mayor Bill de Blasio came because he had displayed sympathy with protesters after Eric Garner’s murderers were exonerated. De Blasio also explained that he has cautioned his son about how to react when confronted by police.

De Blasio, who is white, is married to a Black woman. In this racist society, his children are considered Black.

One of the aspects of racist oppression that has come to the fore as a result of the protests is that fathers (white or Black) who have Black sons regularly counsel them to fear cops, to try to avoid being beaten up, arrested or even killed.

Lynch was put in the national spotlight, by not only the right wing media, but the “mainstream” too. CNN, for example, replayed his rant over and over. The funerals for the murdered cops were featured in hours-long live programming on the main news channels.

This was in stark contrast to the minimal coverage of the funerals for Michael Brown and Eric Garner, and the myriad other victims of the police.

Lost in the din was the fact that the person who shot the two cops was not from New York, had shot his girl friend right before travelling from Baltimore to New York, was a petty criminal, had serious mental health problems and never was part of any of the protests.

The constant pounding of the pro-police propaganda in the capitalist media indicates that more powerful forces than the police have decided to go on the offensive to blunt the protests against police killings.

This push back is having an effect. De Blasio, for example, has ceased talking about police killings and practically trips over himself in praising cops. The latter, sensing blood, have increased their public displays of contempt for him.

Institutionalised racism

The police killings are only one aspect of what has been called “institutionalised racism” in the United States. I prefer the Marxist term “national oppression” of Blacks, which permeates the institutions of capitalist society, from racial segregation in housing to unemployment etc.

National oppression involves more than the ideology of racism. It includes systematic economic super-exploitation and forms of political domination. Just one statistic: the average total wealth of white families is eight times the average wealth of Black families.

The police are on the front lines of enforcing this national oppression, especially in the economically segregated Black communities. Their job is to harass continually and keep these communities in line.

The examples of the “crimes” of Michael Brown and Eric Garner which led to their deaths are cases in point.

Michael Brown’s “crime” was walking on a suburban road. Officer Wilson confronted him, shouting that he should “get the fuck off the street and onto the sidewalk”. Brown, angered and offended, challenged Wilson, who gunned him down.

Eric Garner had been regularly harassed by police for selling individual cigarettes on the street – the “crime” is not paying a few cents in taxes. The day he was strangled, he wasn’t even selling cigarettes. The cops began to harass him anyway. When he protested, he was strangled and suffocated.

Such harassment, usually not going so far as murder, occurs thousands of times every day. That’s why parents of Black boys counsel their sons to fear the police.

A force of reaction

The police are charged with enforcing local and state laws. This includes responding to the murders, thefts, etc. depicted on TV police shows. But the major role of all the armed forces of the capitalist state is to protect capitalism, including capitalist property and values extending to all aspects of society.

While the police are by and large drawn from the working class, including many Blacks, Latinos and Asians, they become an anti-working class force by the nature of their jobs. This is seen clearly when they enforce capitalist law and order by breaking strikes and protests.

At times in US history the police have been beaten back by strikers. When this has happened, state National Guards and even the national army have been deployed.

The anti-working class nature of the police is evident when they attack social protests, as they did in Ferguson. In the civil rights struggle of the 1960s in the south, the photos of police beating, using water cannons and attack dogs against, and condoning racist vigilante attacks on protesters became infamous.

It was the police who were called in to break-up the Occupy protests in 2011. In Occupy Oakland, near where I live, the police fired a “non-lethal” round into the head of a protester, an anti-war veteran of Iraq, fracturing his skull.

The Patrolmen’s Benevolent Associations are sometimes referred to as “unions,” even by officials of the labour movement. But they are not workers’ unions because they are an anti-worker force. One of their main jobs is to defend police against charges of brutality and, in the cases being raised, murder.

They are a force against the Black oppressed nationality, as is quite evident in the positions they are taking against the new Black protest movement.