Michael* is a network technician at Frontier Communications in southern California and a member of the Communications Workers of America (CWA) District 9. In October, Michael and his co-workers struck twice for six hours at a time. They claim Frontier engaged in “unfair labor practices” (a term in US workplace law for actions by employers that violate the National Labor Relations Act) after management threatened to discipline workers, including Michael, who raised safety concerns.

On a usual morning, Michael’s jobs for the day are pre-loaded onto a handheld device. When Michael and other technicians downed tools, it created a backlog of more than 2,000 jobs. The impact of the strike was amplified by the participation of the dispatchers, fellow CWA members, who upload the jobs onto the workers’ devices. When management contacted outside dispatchers at call centres in nearby states, hoping they would reschedule the jobs with contractors, those dispatchers, also CWA members, refused to cross the “digital picket line”. Each strike cost the company at least US$3 million in fines from California’s Public Utility Commission for uncompleted jobs.

Michael told Red Flag that he is “usually a fairly passive guy”, but that his politics became more radical after the Black Lives Matter movement and the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on his community and workplace. “The history of unions”, Michael argues, “shows us that for beneficial outcomes in a time of struggle, a militant response is needed”.

Michael isn’t the only one in his family who took action during a month now widely referred to as “Striketober”. Michael’s partner Patricia* is a nurse working for healthcare company Kaiser and a member of the United Nurses Associations of California/Union of Health Care Professionals. She recently participated in a ballot in which 96 percent of workers in a membership of 24,000 approved strike action. They join upwards of 50,000 Kaiser workers across several states preparing to strike after the company proposed an annual pay rise of just 1 percent.

Patricia’s and Michael’s struggles demonstrate several common themes in workplaces across the US that have contributed to the events of Striketober. Both work on contracts with separate tiers for workers hired before and after a certain date. Both have been offered a pay rise substantially less than the current annual rate of inflation of 5.4 percent. Both have encouraged co-workers to become active members of the union despite their own reservations about union officials. And both are tired of empty rhetoric by politicians celebrating “essential workers” while doing nothing to improve their lives.

Alongside coal miners in Alabama and nurses in Massachusetts who have each been on strike for eight months, there have been strikes, in October, of whiskey distillers, bus drivers, hotel workers, teachers, academics and more. Fast food workers continue to organise walkouts for an increased minimum wage and a union. On 15 October in Sioux City, Iowa, the predominantly Latino workforce at a Curly’s/Smithfield food processing plant marched out to chants of “Sí, se puede!” (“Yes, we can!”—a strike chant first popularised in 1972 by Dolores Huerta and the United Farm Workers).

The total numbers involved in the strikes aren’t high by historic standards, particularly after a strike called by 60,000 film and television studio workers was averted when a tentative agreement was reached. But the strikes do mark a return to a modest upswing in industrial action that began before the pandemic. In 2018, teachers made up the majority of 485,200 US workers who went on strike, the highest number involved in work stoppages in a year since 1986. In October 2019, 48,000 members of the United Auto Workers (UAW) went on strike at General Motors alone, more than the total number of US workers on strike this October.

The recent uptick in strikes, while perhaps not qualifying as a “wave”, in its social and political context appears ripe with new possibilities. Some workers are feeling confident because of a tight labour market. As Johnnie Kallas of Cornell University’s Labor Action Tracker told Real News Network, “We are witnessing a unique opportunity for many workers who have been on the front lines of a global pandemic and recognise that employers are struggling to hire”. This has manifested not just in strikes with stronger demands, but also a record number of resignations. For others, the labour shortage has led to a rise in forced overtime, a catalyst for strikes in steel production, food processing and health care.

So far this year there have been at least 30 strikes of healthcare workers in pandemic hot spots where understaffing, deteriorating conditions, and the extreme demands of the job have worn people’s patience thin. Jamie Lucas, executive director of the Wisconsin Federation of Nurses and Health Professionals, told Politico: “From our members, I’ve never heard the word ‘strike’ uttered so many times, whether they’re covered by a contract or not. Whether they’re in negotiations or not. They’re fed up. The reasons have always been there, but there’s a new realisation that they have the upper hand”.

A strike at Deere, a farm equipment company, began after 10,000 workers represented by the UAW rejected a collective bargaining proposal that reinforced a tiered system in which different sections of the workforce have different rights and conditions. UAW officials were caught by surprise when the contract they negotiated was rejected by 90 percent of the voting membership. That original proposal included an annual pay rise below inflation and would have completely eliminated pensions for all new hires.

The determination of Deere workers to strike was fuelled in part by an awareness of the company’s massive profits and increased executive compensation during the pandemic. One reason they are feeling confident is a shortage of parts created by global supply chain disruptions. The shortage has prevented Deere from building up inventory to tide it over during the strike. Deere has tried using its office staff to replace striking workers on the production line—a move that resulted in a number of accidents, leading to multiple ambulance calls. On 2 November the workers voted down a second contract proposal by a margin of 55 percent to 45 percent, and the strike will continue.

A strike at Kellogg, a breakfast cereal company, involves 1,400 members of the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers' International Union and was sparked by similar issues. Workers there are holding out against another two-tier contract. One of the strike captains at Kellogg, Jason Schultz, a 44-year-old forklift operator, was photographed standing alone, staffing a picket line by himself through an intense rainstorm in the middle of the night. When VICE News asked about the viral image, he responded, “Many will see one person [in the photo]. To me, that is over 1,400 brothers and sisters standing as one”.

As they move into action, many unionised workers are bumping up against the management-friendly approach of their unions’ officials. This became starkly apparent with the rejection of two-tier agreements across multiple workforces. The two-tier model was first popularised in the 1980s and has been championed since then by officials subscribing to the business union strategy—an approach characterised by top-down, management-friendly control of the union. A sudden wave of rejections of these kinds of agreements by rank-and-file activists is a positive development in the US labour movement.

Within two of the biggest unions in the country—the UAW and the Teamsters—a related battle is underway. Unite All Workers for Democracy (UAWD) is a democratic reform movement within the UAW that emerged after a series of corruption scandals. UAWD calls for direct elections of union leaders rather than the current delegate system. In the Teamsters, where direct elections were enacted after their own corruption scandals years ago, an ongoing election process, which will be finalised in November, pits a faction endorsed by the outgoing president, James P. Hoffa, against an insurgent faction that claims to be more militant. Hoffa is widely despised by Teamsters members after he ratified a two-tier agreement covering 280,000 workers at UPS in 2018 even after union members voted to reject it.

“Socialists”, as long time Teamster Joe Allen put it in an article on Striketober in Tempest Magazine, “need to actively organize rank and filers to work with union officials when they fight for us but act independently of them when they don’t”. This is a lesson being learnt in real time, it seems, by many workers on the front lines of the class struggle in the US today.

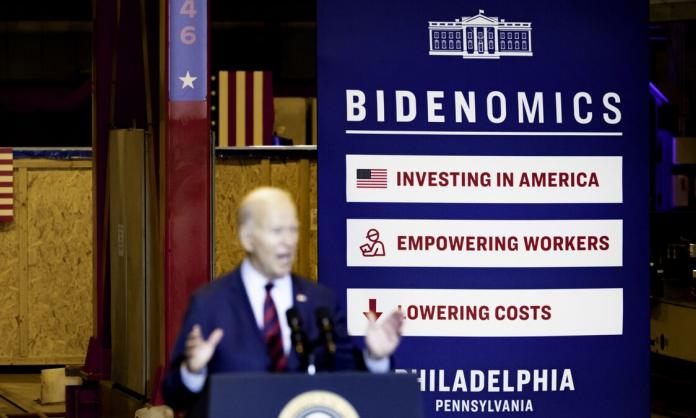

Amid this apparent rank-and-file rebellion, there are also questions about the US labour movement’s ties to Democrats and expectations of the Biden administration. Top union officials have maintained loyalty to the president. One, president of the American Federation of Teachers Randi Weingarten, went so far as to tell McClatchy, “Frankly, I don’t know another president who’s done this much for labour”. Other officials and union members have voiced discontent with the administration’s relative inaction throughout Striketober. Marlena Pellegrino, one of 700 nurses on strike for eight months at Saint Vincent Hospital in Massachusetts, told NBC News she was unsure about Biden’s commitment to workers. “It is time for someone to step up”, she said. “We would absolutely love and implore the president to get involved. There hasn't been any direct involvement at that level.”

Biden sent his labour secretary, Marty Walsh, to speak at a Kellogg workers’ picket line in Pennsylvania, and the agriculture secretary, Tom Vilsack, visited a Deere workers’ picket in his home state of Iowa. This kind of support, however, is purely symbolic.

Meanwhile, negotiations with Senate Democrats over Biden’s proposed infrastructure bill have significantly whittled down the original commitment of US$3.5 trillion—jettisoning much of the social spending and other provisions that could have improved US workers’ position somewhat. Unionists like Michael and Patricia have been particularly disappointed with the inability or unwillingness of Biden to deliver more for workers in this marquee bill.

Kellogg workers in Michigan say most of their co-workers vote Republican but are keenly aware of the lack of support for their strike from the party. Quotes on this topic from strikers—published in the Detroit Metro Times—show a marked shift in consciousness. “You should be doing what’s best for everybody and not [just] you or a select group of people like you”, says one. “Whether you’re blue or red, certain things just transcend that, and getting everybody treated equal should fall in that line”, says another.

At a Deere picket line in Iowa, this trend went even further. Allen’s report in Tempest quotes a UAW delegate who was met with loud cheers when he declared, “It’s no secret there’s been political conflict on the shop floor. But I say it’s time to put those differences aside. We need to unite against a greedy corporation, we need to unite around what we have in common and that’s that we are workers. We need solidarity”.

Across the political spectrum, support for labour unions is at its highest since 1965, according to polls by Gallup. Polls by More Perfect Union and Blue Rose Research show that low income and non-college-educated Americans are among the strongest supporters of organised labour and strikes.

An energised and militant labour movement could potentially revive unionism in the US after decades on the back foot. But the movement can’t rely on support from the Democrats any more than from the Republicans: both parties exist to serve big business interests counterposed to those of workers. The rising class consciousness expressed by workers in Striketober has, unfortunately, no significant political force to cohere and organise it. Alongside building the labour movement, the project for socialists in the US, as in Australia, must be to build an independent political force of that kind.

*Names have been changed.