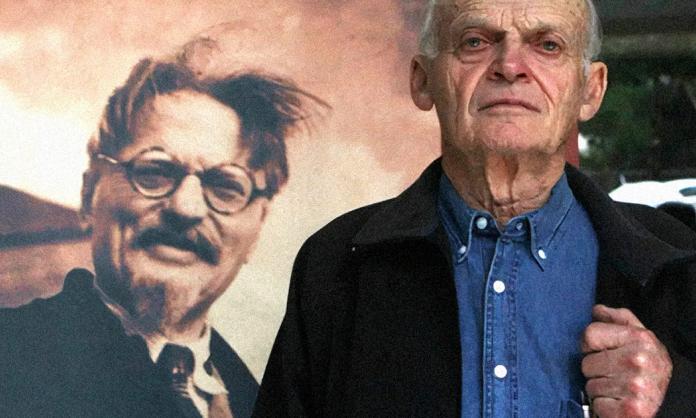

Esteban Volkov was just 13 when, in May 1940, Stalin’s assassins tried to kill him. Why? Because his grandfather was Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky.

Born in Yalta, Ukraine (then part of the Soviet Union) in 1926, Esteban was the son of Trotsky’s daughter Zinaida and her husband Platon Volkov. At the time, Platon was a prominent member of the Left Opposition, led by Trotsky. The pair were both vocal critics of Stalin’s increasingly rightward leadership of the USSR.

In particular, Trotsky viewed Stalin’s China policy as a complete departure from the internationalism and class independence that Lenin and the Bolsheviks had advocated. Stalin, who had succeeded Lenin as party leader, argued that the Chinese communists should disband and fuse with the pro-capitalist Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party), claiming that it was the only force capable of defeating the occupying imperialist powers.

This proved disastrous when, in April 1927, Kuomintang leader Chiang Kai-shek massacred hundreds of communists and their supporters in Shanghai, opening the way for anti-communist purges across the country.

Trotsky had been proved right. Stalin responded by exiling him to Alma Ata in Central Asia and then banishing him from the Soviet Union two years later. He subsequently stripped Trotsky and his family of their Soviet citizenship, rendering them stateless.

The repression didn’t stop there.

Platon was murdered by Stalin’s agents, forcing Zinaida and her 5-year-old son, originally named Vsevolod, to join Trotsky in exile on the Turkish island of Prinkipo. From there they moved to Berlin. Sick with tuberculosis and separated from her family, Zinaida became deeply depressed. In January 1933, on the eve of the Nazis taking power in Germany, she took her own life. Vsevolod, now an orphan, was sent to a Vienna boarding school before joining his uncle, Trotsky’s son Lev Sedov, in Paris.

Paris offered a haven for Vsevolod, and an organising centre for the Trotskyists. However, Stalin’s agents were in hot pursuit. In 1938, Sedov died in suspicious circumstances following an appendectomy at a Paris clinic. It was suspected he had been poisoned, though the case was never proven.

Orphaned again, Vsevolod remained in the care of his uncle’s widow before leaving Paris in 1939 to join his grandfather in Mexico. There he adopted a Spanish name—Esteban.

Trotsky and his wife Natalia Sedova had arrived in Mexico City in January 1937. With the help of Mexican painter and communist Diego Rivera, they acquired a villa in Coyoacán, surrounded by a very high wall. Coyoacán was then a tranquil town on the outskirts of Mexico City; today it is a trendy inner-city suburb.

“I was thirteen and a half when I first arrived in this house—from Paris, with Alfred and Marguerite Rosmer”, Esteban recalled in a 2017 interview with Left Voice. “The contrast was stark. Europe in winter is grey, grey, grey. I came from a sinister climate full of grief. After the death of my uncle Lev Sedov, I was emotionally damaged.”

Esteban described taking trips into the countryside with Trotsky, who had become an avid collector of cacti: “My first impression was: Colour! Mexico is a country full of colours”.

This blissful life was soon rudely interrupted.

In the early hours of 24 May 1940, a group of Stalin’s henchmen, led by painter David Alfaro Siqueiros, breached the compound in which Trotsky and his family had found sanctuary. The front gate was opened by Sheldon Harte, a Stalinist agent who had infiltrated the US Socialist Workers Party, which had entrusted him to act as Trotsky’s bodyguard.

Once inside, the men sprayed machine gunfire into the bedrooms where Trotsky, Natalia and Esteban slept. Natalia jumped out of bed and pulled Trotsky out of the line of fire. Esteban awoke and hid behind his bed until the shooting stopped. Natalia suffered burns; a bullet hit Esteban’s big toe. It was a lucky escape.

Half a century later, when the Soviet archives revealed the government’s hidden secrets, Esteban discovered that Harte had criticised his comrades for wanting to kill a child. For that, Harte was branded a traitor, killed and buried in a park.

“That is how the Stalinist system worked”, Esteban told Left Voice. “When something went wrong, you had to find someone to blame. And in this case, it was very easy to blame the American.”

With funds raised by the Socialist Workers Party, the compound was now fortified: windows were bricked up and bunkers were constructed on the roof to protect against would-be assassins. “Grandfather [Trotsky] was basically a prisoner in his home”, Esteban recalled.

Three months later, on 20 August, another Stalinist agent succeeded in his mission. The assassin, a Catalan named Ramón Mercader, had been a Soviet secret police agent during the Spanish Civil War, working to subordinate the forces of revolution to Stalin’s dictates. He drove an ice pick into Trotsky’s skull while he sat reading at his desk.

“When I went into the study, I saw Lev Davidovich [Trotsky] wounded, lying on the ground, but the guards and others stopped me from going any closer”, Esteban recalled in a 2003 Guardian interview. “My grandfather had said: ‘Don’t let Seva [Esteban] in, the child mustn’t see this’. Later, he crossed the garden for the last time, on a stretcher carried by male nurses.”

Trotsky died in hospital the next day.

“The more grotesque lies about Trotsky have disappeared with the regime that manufactured them. But there still exists another distortion, the one that equates Trotsky and Stalin as two bad Russian bears”, Esteban told the Guardian.

“But it went deeper than a personal power struggle. It was a conflict over what type of society the Soviet Union should be. Stalin was the builder of a bloody, oppressive and bureaucratic system. Trotsky led and defended a revolution. There is no comparison.”

After Trotsky’s assassination, Esteban remained in the house with Natalia, who died in 1962 at the age of 79. He trained as an engineer, developing technology that enabled the mass production of the first contraceptive pill. He married and raised four daughters in the same home.

But his greatest legacy was his contribution to keeping alive the ideas of his grandfather.

In 1990—50 years after the assassination—Esteban opened the doors of his family home to the public, establishing a museum to honour Trotsky’s life and an institute to promote the rights of those seeking political asylum. The museum displays Trotsky’s study as it was at the time of his assassination. Behind the house stand a library, art gallery and meeting venue.

Esteban passed away peacefully on 17 June at the age of 97. He is survived by his four children and was cared for in his final years by Gabriela Pérez Noriega, now the director of the Leon Trotsky Museum.

Esteban Volkov’s work is evidence of the motto: “You can kill a man, but you can’t kill an idea”. He stood in a proud tradition of opposition to Stalinism and support for the idea of an internationalist, revolutionary socialism.

Esteban Volkov presente!