Tom O’Lincoln, who died on 13 October 2023 aged 76, was a committed Marxist and revolutionary virtually his whole adult life.

Born in Walnut Creek, near San Francisco, Tom became interested in politics during the eventful 1960s. He joined a civil rights picket aged 14 and campaigned to stop right-winger Barry Goldwater’s presidential nomination. The anti-Vietnam War movement awakened more serious political interest. But it was as an exchange student in Germany in 1967-68 that Tom became radicalised. He joined the SDS, the German socialist student organisation, and started to read Marx and Lenin. He protested against the Vietnam War, participated in an attempted blockade of the right-wing Springer Press and saw the first round of the student movement in Paris in February 1968.

In August 1968, I met Tom completely by chance at a youth hostel in Paris. I will never forget him coming downstairs one morning to say breathlessly, “I’ve just heard on the German news that the Russians have invaded Czechoslovakia”. From the beginning, our relationship was conditioned by the political environment.

By this time, Tom considered himself a Marxist; as he says, he had “crossed a boundary in attitude”. Quite characteristic of his life as a political activist he goes on: “I took [an] interest in listening to political argument and ideas back with me to Berkeley”.

The following year I joined Tom in the US. Tom was looking for a politics that would “make revolution inseparable from democracy”, which he found in the International Socialists in Berkeley, where he was a student.

This was the major turning point in Tom’s political life. In the Berkeley IS, he became committed to the principles that guided his political activity, his values, his beliefs and his intellectual life until his death.

Crucial was the concept of socialism from below and an understanding of the central role of the working class, support for movements against oppression, internationalism and the importance of struggle. Tom acted on these principles throughout his life as a rank-and-file trade unionist, as an activist, as a leader in the various forms of the Australian IS, as a supporter of socialists in Indonesia, as a writer, and in all his political positions.

Not long before his death, when asked about the political highlights of his life, Tom responded: “The key experiences share the common element of seeing the process of radicalisation in action. Examples include the actions against the war in Vietnam, the growth of the New Left and later the mobilisations against the Fraser government. For me, what made these so important was that the level of rebellion was high”.

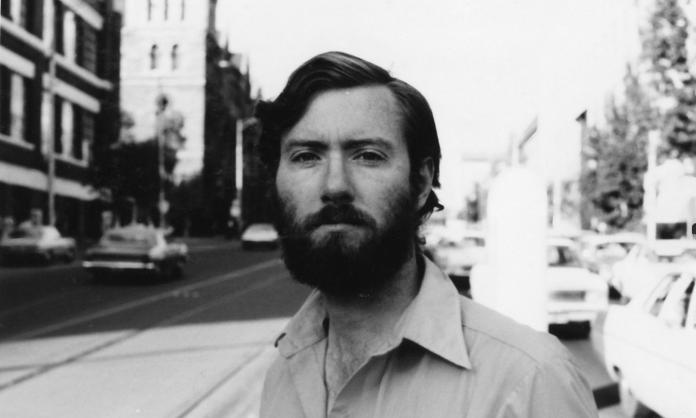

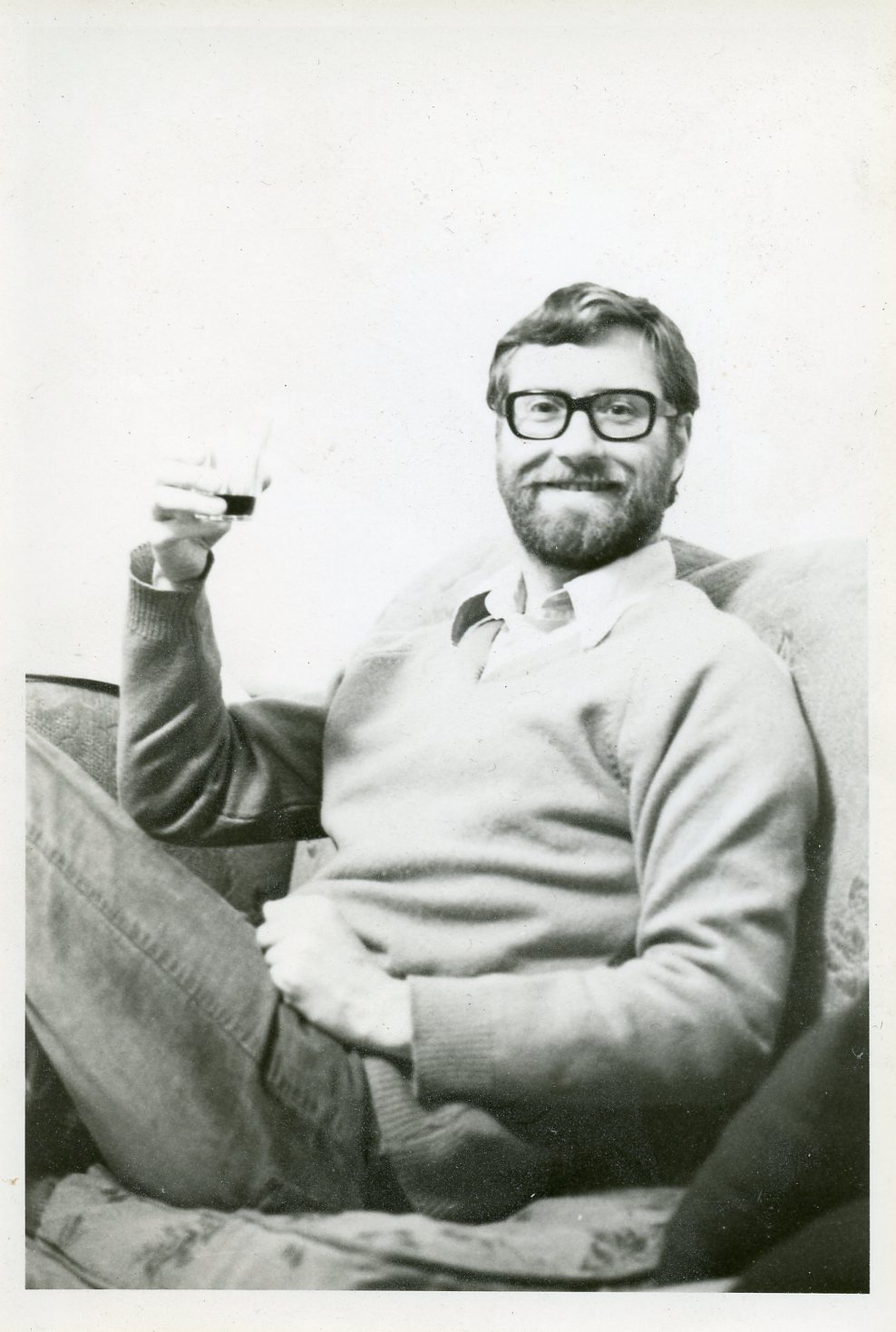

Tom did not look, however, like a typical rebel. Most of his life his hair was relatively short and his glasses made him look rather conservative. He was once able to get out of an attempted bottling of demonstrators by straightening his collar and calling a police officer “sir”! Even with a beard he didn’t look like a rabblerouser. His speaking style was not flamboyant, his voice was not loud and his gestures were restrained.

This contrasted strongly with the radical content of what he said. In his arguments, Tom pulled no punches. But also in his personal reactions to radical people and events he showed his radicalism. His enthusiasm for the Black Panthers in Berkeley, with their jaunty hairdos and radical stance, was infectious and I sported a Jewish-Afro for a while under this influence. Tom always cheered on striking workers, street protests of the oppressed and national liberation struggles.

Tom and I came to Australia in November 1971 intending only to stay a couple of years before resuming travel. But again, circumstances intervened that changed the course of our lives and those of many others. At Mayday 1972, we encountered the very small Melbourne-based Marxist Workers Group and started to work to create an organisation which would reflect the politics that we stood for. Although he did travel again, Tom settled permanently in Australia and devoted himself to Australian politics for the rest of his life.

At first, Tom worked as a teacher and later he became a public servant. He also worked for a while as a sheet metal worker, and had stints doing full-time political activity. Wherever he was, Tom followed the news, read widely, talked to people and made friends.

Tom didn’t worry very much about his reputation. In the mid-1970s, he attended a demonstration for what was then called gay rights, wearing a very conspicuous jacket. When his pupils at school recognised him on TV, they asked disingenuously: “Are you a poofter, Mr Lincoln?” Tom just smiled.

Many people have attested to Tom’s lasting intellectual impact on them. For decades, he led reading groups to study Marx’s Capital, gave talks on subjects ranging from political economy to Australian labour history, wrote articles about international and local events and developed position papers on subjects such how we understand the role of Israel. Tom was always ready to discuss politics with people whose political position was different from his own. His patience in explaining issues to new comrades is remembered by many.

Tom said to me that he was not an innovator in terms of Marxism, but rather a populariser. And it is true that he had a special talent for explaining complex material in a very accessible way. A recent example is the translation earlier this year into Korean of a pamphlet he wrote in the 1980s about state capitalism. This piece is exemplary in its clarity, conciseness and purposeful exposition. It is not surprising that a Korean group would find this fairly obscure piece of writing useful today.

The ability to present complex ideas to a new audience is no mean talent—it is not “only” being a populariser as it requires a very profound understanding of the material. But I would argue that Tom in fact was a path breaker in his books and not just a populariser. His short history of nineteenth century Australian labour history, United We Stand, was published in 2005. In the preface to the forthcoming new edition, historian Terry Irving comments that Tom was writing from within the working-class movement—“the first book of this kind since Brian Fitzpatrick’s Short History of the Australian Labour Movement (1940) to be able to claim this distinction”.

Tom developed his analysis of Australia as not simply a colony subject to the UK or (later) the US, but as being a “boutique” imperialist power in its own right in the region. He presented this argument in his books The Neighbour From Hell and Australia’s Pacific War. This was also breaking new ground.

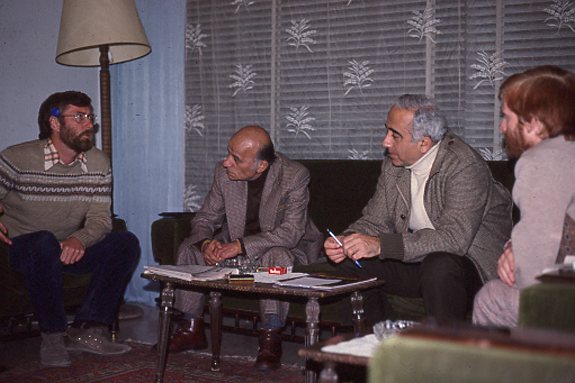

Tom had a talent for languages. He spoke German fluently and studied Hegel, Marx and others in the original. He taught himself sufficient Portuguese when we were in Lisbon in 1975 to be able to speak to workers occupying factories. His fluent French proved very useful in Beirut in 1980. Tom had political discussions with workers and leftists in Spanish in Nicaragua and Peru in 1985. At this time, he also was reading in Spanish about the Peruvian Marxist José-Carlos Mariategui.

In the 1990s, Tom studied Indonesian, eventually knowing it sufficiently well to set up Suara Sosialis (Socialist Voice), a six-year-long project to produce Marxist material in Indonesian. He not only read and spoke the language but made a special effort to master colloquial expressions. His knowledge proved useful in June 2001 when the Asia Pacific Solidarity Conference near Jakarta was raided by police. Tom acted as interpreter for many of the foreigners in the group and helped negotiate the release of those arrested.

But it was Tom’s English language skills that influenced so many. From the beginning, Tom taught members to write simple, concise English which set forward Marxist ideas clearly. Editors of the publications from the Battler on were strongly influenced by Tom’s style; I and many others turned to Tom for advice when writing longer articles and even books. His skills as an editor, and his ability to improve a piece by shortening it, have repeatedly been enlightening to me. Tom’s influence lives on today in a wide network of political writing that does not bear his name, but is indebted to his example and guidance.

Tom was not just interested in political writing. His engagement with literature enriched his appreciation of Marxism and political theory, of history and of the world. In an unpublished essay on Faust, he wrote:

“Great literature is valuable even if it’s written by bilious right wingers. A famous example is the work of Balzac ... Engels wrote that he had ‘learned more [from Balzac] than from all the professional historians, economists and statisticians put together’.”

Tom’s political influence on me was profound. I joined with him and others in building political groups in the 1970s and 1980s and remained close to him politically after I ceased to be a member in the early 1990s. We experienced many political highlights together. In Portugal in July 1975, we joined in mass working class demonstrations. Back in Australia later that year, we were part of the protest again the dismissal of the Whitlam government that marched down Bourke Street in Melbourne.

In the following period, we were together in many actions against Liberal Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser. We visited Lebanon, Syria and Israel/Palestine in 1980 together with Mick Armstrong, and in 1985 we travelled through South America and Nicaragua. Tom encouraged and inspired me—he helped me to learn to speak in public, to write about the activities I was involved in, such as women’s liberation, to develop political interests of my own, such as the radical Jewish movement, to write and to be an activist.

In 2012, Tom was diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease. Sadly, as the disease slowly took hold, he went into care and became unable to write. His last published piece was “Dementia is not a democracy: looking for freedom in an old folks’ home”. But he continued his political activity as long as he could—he attended meetings of Socialist Alternative from his aged care facility, he watched the news, he talked about the political situation and enjoyed the new editions of his books. Almost the last thing he said to me just four days before he died was about the war in the Middle East.

Tom was my political mentor virtually all my adult life. He was my partner for nearly twenty years and after that was one of my closest friends. Throughout, I looked to him for guidance and comment in my writing and political activity.

But we were more to each other than comrades. When we parted, we agreed that we would look out for each other and support each other in life. We did that until the very end.

Tom began his political memoirs with a quote from William Faulkner: “The past is not dead. It is not even past”. Although I now say good-bye to Tom, he does not seem really gone. He lives on, not just in me but in the dozens and hundreds of people who learnt from him, cared about him, were politically active with him, read his books, listened to his talks, and are now reading his obituaries. When asked, “Why be a revolutionary socialist today?”, his answer was that it was a life worth living.

His life was truly a life worth living.