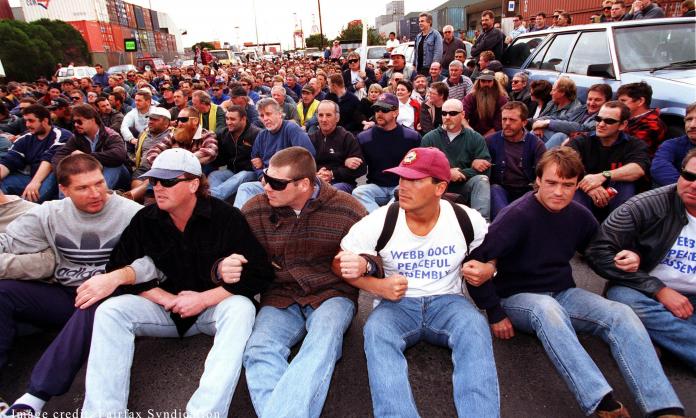

Twenty years ago, on 7 April 1998, Patrick Stevedores dismissed and locked out all 1,400 of its unionised waterside workforce, triggering mass protests and picketing around the country.

In the dead of night, balaclava-wearing scabs with German shepherds and rottweilers entered the docks, catching wharfies on night shift by surprise. In short order, every worker was stood down and forced off the premises.

The lines of division in Australian society were laid bare for all to see. Companies had contributed close to $100 million to a fighting fund set up by the National Farmers’ Federation to destroy the MUA.

The offensive, coordinated by the Howard government, also involved a well-orchestrated media campaign against the wharfies, portraying them as overpaid bludgers intent on destroying the economy.

Australian columnist Alan Wood gloated a couple of days after MUA members were locked out: “Hard as it is to believe, it really looks like it is all over on the wharves, bar the shouting … The MUA’s monopoly of waterside labour is doomed”.

But in each of its major aims – to bust the MUA and to use this as the first step for an offensive against other unions, to introduce scab labour onto the wharves and to intimidate other unions with the successful use of anti-union laws – the government and the bosses failed.

The wharfies walked back through the gates after being reinstated by the courts. The MUA retained union coverage on the docks. The scab company PCS Stevedores was driven off the waterfront.

The actions of tens of thousands of trade unionists and their supporters proved that unions are still critically important. Solidarity, mass picket lines and the language of class struggle forced themselves back onto the industrial and political agenda in Australia.

How did this come about?

Tens of thousands of supporters were drawn to support the MUA by sheer outrage at Patrick’s industrial thuggery. If the wharfies were beaten, no union was safe. And a common enemy in the Howard government, with its agenda of union bashing, welfare cuts, racism and privatisation, linked all those who came to the picket lines.

Within days, telephone trees of thousands alerted supporters when the police made any move. In Melbourne, Sydney and Fremantle, workers and other supporters gathered night and day at picket lines, giving the scabs hell and bringing food, ideas, music and whatever skills they had. The exhilaration of turning away trucks from the docks was tremendous.

The high point was the night of 17 April, when thousands turned up at East Swanson Dock in Melbourne. On a tip-off that 1,000 police would be coming to break the picket line, 4,000 picketers had gathered by 3am to repel them.

At 8am, nearly 2,000 construction workers arrived at the picket line and encircled the cops, forcing them to retreat. Nothing moved into or out of the Port of Melbourne. This was the biggest victory won by the trade union movement for many years.

For many union activists, the dispute was a new and energising experience, reviving confidence that when workers stand and fight together, they can resist the government and the bosses.

But the lessons from the dispute were not just positive ones.

Although Australian unionists have every right to be proud of the tremendous struggle waged by the MUA and its supporters in the first half of 1998, our side took serious casualties.

Half the Patrick workforce soon lost their jobs. Working conditions were driven down and the pace of work intensified. Patrick took the opportunity to step up its casualisation of the labour force. These setbacks were gradually generalised across the entire waterfront.

There was nothing inevitable about this. There was potential for more strike action than the leaders of the MUA and the ACTU contemplated.

Offers of industrial solidarity had been coming in even before the MUA members were locked out. On 2 April, members of the Australian Workers’ Union in the oil industry promised to strike the moment Patrick workers were sacked.

Throughout April, warehouse workers from the big supermarket chains, building and construction workers, truck drivers, metalworkers and coal miners all took action and turned up in large contingents to lend support to the wharfies’ cause. Not a single worker was fined for doing so.

Other unions announced that they would take illegal strike action to support the MUA if the call came. The South Australian United Trades and Labor Council promised support for a general strike if one were called by the ACTU and MUA.

Instead of using this massive potential, the MUA and ACTU leaderships rationed it to support a strategy focused elsewhere – on the courts and the ALP.

Yet the court decisions were favourable only because of the mass working class mobilisation. As for the ALP, not once during the industrial campaign nor in the later federal election campaign did it suggest that it would repeal the anti-union laws.

The government and the bosses assumed that they would quickly isolate the union. They were not prepared for the mobilisation in defence of the wharfies. While the MUA and ACTU leaders were prepared to sanction a limited amount of illegal industrial action, rank and file union members showed that they were prepared to do more.

Had the union leaders given a lead to this mobilisation from below, the union movement would be in a much better state to take on the fights we face today.

Material for this article was taken from Tom Bramble, War on the Waterfront: the MUA Dispute, published by the Brisbane Defend our Unions Committee.