In the preface to his History of the Russian Revolution, Leon Trotsky wrote that the “most indubitable feature of a revolution is the direct interference of the masses in historical events”. Chile in the early 1970s was a society embroiled in such a process, as workers fought with growing strength and self-confidence to build a new society under—and at many points, in spite of—Socialist Party President Salvador Allende and his Popular Unity ruling coalition.

Peter Winn’s gorgeous Weavers of Revolution, an oral history of the workers’ struggle at the Yarur textile mill through the 1960s to the bloody coup led by Augusto Pinochet in 1973, animates Trotsky’s words through the story of one factory. It’s a compelling portrait of the Chilean working class, a tapestry of its personalities, passions, anxieties, hopes and courageous partisans, battling for three electric years to reshape radically the world around them.

The Yarur story is both an element and embodiment of the broader Chilean workers’ struggle, which radicalised sharply through 1972-73. As Winn illustrates, each decisive point in Chile’s revolutionary process involved not only the machinations of Popular Unity and the political right, but huge exertions of popular muscle—of which Yarur was a crucial sinew.

The story of Chile’s revolutionary process normally begins with Allende’s election in late 1970. But Allende’s rise reflected a growing militancy amongst workers and peasants through the latter years of the 1960s, characterised by a spate of unauthorised land seizures and growing strike action. So too, the Yarur story began many years before the election of Popular Unity, with an attempt to win an independent union inside one of the country’s most notorious workplaces.

Life inside the flagship Yarur mill in Santiago resembled a dictatorship. It was named after its owners, the Yarur family (“rich as Yarur” was a common saying). For decades, Yarur had staved off unionisation attempts through a mixture of patronage, company unionism and repression. The firm cultivated a network of loyalist workers as informants, making independent union agitation risky; rebels were punished mercilessly, deterring sympathisers. The crushing of a nine-week strike in 1962 instilled a pessimism amongst older workers, who were wary of young activists promising change.

Against this difficult backdrop, young leftist workers, many of them in the Socialist Party, the MIR (Revolutionary Left Movement) or, to a lesser degree, the Communist Party, began a tooth and nail fight to build underground cells in the factory and win a free union. Facing routine sackings, bribery and even death threats, they fought a clandestine campaign to convince workers of their cause. Ingenious plots were employed, like disseminating leaflets through the factory’s ventilation shafts.

Efforts to organise Yarur came to a head during the 1970 national election campaign. Company boss Amador Yarur invited Allende to speak at the factory, hoping to win favour on the chance that he was elected. It was a coup for the free union activists. Hundreds of workers attended, and their material was at last distributed openly. Two clandestine cells operating in different departments of the factory even learned of each other’s existence for the first time.

On the eve of Allende’s election, the free union activists captured the company union with a smashing four-to-one victory—a decisive mandate to begin a campaign to transform the factory. It was emblematic of a trend all over Chile: workers beginning to organise, their efforts both reflected and focused by the election of a genuine reformer.

Allende’s victory likewise inspired confidence amongst the Yarur workers. Nationalisation of Chile’s monopolies was a key plank of the Popular Unity program, and workers were impatient to play their part in the transformation of the country. In April 1971, 1,700 Yarur workers went on strike in retaliation to Amador Yarur’s decision to stop communicating with their new union. They demanded that Yarur be turfed out and the factory taken over by the state.

To Allende, though, the nationalisation of monopolies was a distant task contingent on another election victory in 1976. The first tranche of nationalisations would include only foreign-owned companies like the copper mines, and companies that had been sabotaged or abandoned. Workers in the domestic monopolies would simply have to wait. But the Yarur workers had already waited for decades.

Their strike sent a shock wave through the government. To his ministerial staff, Allende raged at the idea of nationalising Yarur: “If I give the OK to this ... there is going to be another and another ... just because one was already gotten out of me”. Workers would face the resistance not only of their boss, but of their supposed compañero too. Admirably, they persisted, continuing the strike and confronting Allende at the Presidential Palace to put the case for nationalisation.

In Weavers, Winn captures the tense exchange between the workers and government officials, recounting strike leader Ricardo Catalan’s explanation that they “had a duel with el compañero presidente”. What was at stake was not only the goal of nationalisation, but the confidence and aspirations of nearly 2,000 workers who had embarked on the imposing task of making their own destiny after years of belittlement and intimidation. Strike leaders writhed with anguish at the thought of letting their workmates down.

They stood firm, and the strike split the different Popular Unity component parties, winning support from figures in the left of the Socialist Party who favoured a bolder approach to nationalisations. Allende was forced to relent, to the jubilation of the strikers. “The joy was really indescribable ... something very difficult to translate into words successfully”, independent union leader Jorge Lorca said to Winn. “It was the kind of thing that remains in your mind forever ... At the bottom there was a sense of ... liberation.”

Upon victory, the blue-collar workers saw the opulent, marbled interior of Amador Yarur’s office space for the first time. “It reminded me a lot of that photograph of the Russian Revolution ... of a Russian soldier standing in the throne room looking up ... the same expression of incredulity ... of not being able to imagine the lifestyle and luxury that took place there ... or their own conquest of such heights”, described one MAPU (Popular Unitary Action Movement) activist.

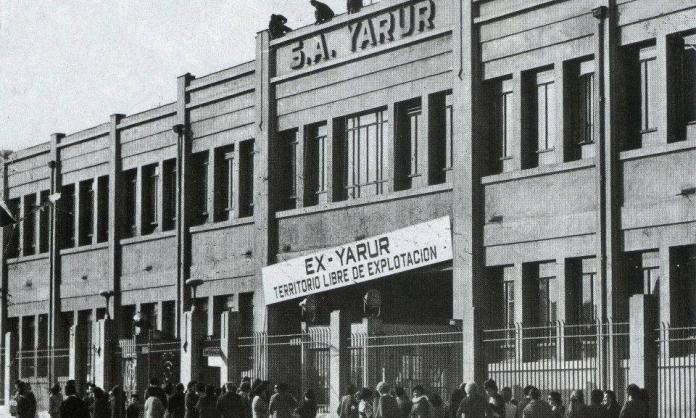

With workers now in charge, they unceremoniously placed a sack over the statue of the company’s founder Juan Yarur and raised a banner at the factory gates: Ex-Yarur: Territorio Libre de Explotación (Ex-Yarur: Territory Free of Exploitation). As Winn summarised, “the Yarur workers became central protagonists of a revolution from below that changed the course of the Chilean road to socialism”.

Yarur was brought into the government’s Social Property Area (enterprises under state control) and placed under a form of co-management that allowed the firm to operate according to a national plan, with worker participation. Whilst not socialist control or planning, this arrangement allowed a significant increase in the agency of workers on the shop floor. Following Ex-Yarur’s lead, dozens of factories followed suit, demanding that their own workplaces be nationalised by Allende.

Before long, Yarur workers would press their involvement in running the factory far further than the scope of the Social Property Area. Alongside many hundreds of thousands of other Chilean workers, they would transform the Allendist slogan “Poder Popular” (Popular Power), into a magnificent reality.

In retaliation to workers’ new-found confidence, the transport bosses and middle-class professionals attempted to paralyse the country in October 1972. Trade union leaders put a call out to workers to defend the government from the bosses’ strike. Factories across the country leapt into action, “interpreting”, as Winn wrote, “the CUT’s [United Workers’ Centre] call for vigilance as a license for direct revolutionary action”.

Workers seized more factories than ever before, turned the nationalised factories over to combat the lockout and began coordinating their activities in the cordones industriales, radical grassroots organisations to restart production without the bosses.

Ex-Yarur helped found the Cordón O’Higgins—one of Santiago’s most significant nerve centres of working-class power—and assisted smaller factories in seizing their own workplaces. Furious workers voted to cut out the merchants and instead distribute materials directly to consumers and occupied garment factories. They formed a self-defence organisation to guard against right-wing violence, and converted the factory’s machine shop to produce parts for trucks so that transportation could continue without the truck owners.

Ex-Yarur’s trajectory—from the fight to win an independent union, to the strike for nationalisation and eventually running the factory under workers’ control—epitomised the struggle of an entire generation.

Eventually, the bosses’ strike collapsed. The cordones represented the high point of workers’ involvement in Chile’s revolutionary process and would again flourish in the months leading up to the September coup.

But when Allende was overthrown by Pinochet on 11 September 1973, the workers of Ex-Yarur suffered on the front lines. In the factory, soldiers under arms took back each workbench and shop, department by department. Murals that had been painted to celebrate workers’ control were whitewashed. Amador Yarur, the hated factory boss, was reinstated.

Pinochet’s coup would brutally end the lives of the finest working-class activists in a generation, including many from Ex-Yarur. It would subject the surviving population to a reign of terror and a miserable life in a laboratory of neoliberalism. Berta Castillo, a young woman worker who had greying hair and stooped shoulders from life in the factory, lost her job, her house and her husband to the counter-revolution. But she later recounted to Peter Winn that “worst of all ... they have killed my dream ... It was such a beautiful dream”.

The defeat of the Chilean workers, amongst them the heroes of Ex-Yarur, would set the class struggle back generations. But their memory of courage and conviction, of militancy and self-reliance even when abandoned by their compañero presidente, of organisational brilliance and heroism as part of the class-wide cordones, should serve to furnish a vision of humanity’s socialist potential. The story of this Chilean textile mill is a glimpse not only of what is possible, but of a world worth fighting for.