“Culture cannot be destroyed by violence”, read the banner held by representatives of the Toho Labor Union on 19 August 1948 as they faced down more than 2,000 police and five American Sherman tanks, “everything but the battleships”, according to actress and unionist Akagi Ranko. Behind the barricades, hastily constructed from set pieces of films in progress, stood a thousand striking workers from every department of the Toho studio in Tokyo.

Kyoko Hirano, in her 1992 book Mr Smith Goes to Tokyo: Japanese Cinema Under the American Occupation, 1945-1952, documents the strike in extraordinary detail. Hirano cites US government documents that describe how large set fans, which faced the strikebreakers like artillery pieces at the barricade, were primed with “shards of glass and sand”, although it was more likely to have been cayenne pepper according to Hirano. Set technicians likewise repurposed rain machines into water cannons. A “defence captain” wearing a cowboy hat emerged periodically at the front of the barricade to crack jokes at the expense of the police. Workers and bosses across Tokyo anxiously waited to learn the fate of the striking Toho stronghold. This fight was to become a critical juncture in Japan’s class struggle.

The Toho company was Japan’s most prominent film distributor, theatre and studio company for the first half of the twentieth century. Western audiences are likely familiar with Toho’s output through Godzilla or Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai.

Before its defeat in World War II, Imperial Japan underwent rapid and brutal industrialisation, the brunt of which was born by the poor, especially the Korean colonial subjects and urban working class. John Halliday writes in New Left Review that most workers “had no rights, no job security (and) no guaranteed wage increase”.

There were few outlets for workers to express discontent; unions were banned or violently restricted to the point of impotence, and activists caught handing out propaganda were known to disappear. The fate of many such activists is recorded in the compilation of pre-war writings, Reflections on the Way to the Gallows, edited by Mikiso Hane.

Anarchist and communist sympathies simmered in the underbelly of Japan’s cities, occasionally culminating in strikes, such as by the Tokyo subway workers in 1932. While victories were few, the strikes were important for radicalising workers and demonstrating the counterposed interests between bosses and workers that could lay the foundations for a socialist current to emerge. An example is the semi-legal Print and Publishing Workers Club, which organised strikes because “what is important is the number of class-conscious activists who will emerge… to actively join the class struggle”, according to Club leader Shibata Ryuichiro.

Hirano describes film studios in this period as being run on an authoritarian auteur model, with creative input from technicians, crew and even actors discouraged. This was seen as the best way to churn out commercially viable films, as staff were kept to a strict timeline and budget, shunted from one project to the next, overworked, and often with little knowledge of the film they were producing.

The initial policy of the US occupying forces in their period of direct control over Japan after the war was towards “democratisation” of the country—they encouraged unions and held elections in the hope that a stable domestic government could be relied on to protect US investments and contain their rival imperialist power, the Soviet Union.

The hitherto suppressed working class exploded into frenzied political activity. Historian Andrew Gordan claims “union membership rose from about 5,000 in October (1945) to nearly 5 million by December 1946, over 40 percent of the nation’s wage earners”. The Toho studio was located in Tokyo’s industrial centre, the heartland of workers’ struggle.

In March 1946, the 5000-strong Toho Labor Union started its first strike. Holding membership across the spectrum of different roles required for filmmaking, from director to caterer, they demanded and won a moderate minimum wage increase. More significant than the pay rise, however, was the workers’ decision to establish a “Struggle Committee”.

Struggle Committees, which first appeared in the mining and transportation industries, comprised elected rank-and-file union representatives who would negotiate day-to-day production with management. By the end of 1946, workers in Tokyo had set up 250 such committees.

The power and politics of these bodies depended wholly on the militancy of the workers. Everyone from careerist hacks to hardcore communist militants was involved in the committees.

Historian Joe Moore, whose works on post-war Japan are an excellent introduction for Marxists interested in the Japanese class struggle, explains the tendency towards radicalisation inherent in these bodies: “[A]t the beginning the Japanese workers did view production control as an effective if unorthodox dispute tactic,” but it was “a short step further to the position that the enterprise need not ever be returned to the control of the owners… they as workers could not only run an enterprise successfully but also do it better than the capitalist owners.”

The films of the Toho workers from this period display the workers’ growing confidence as eloquently as any written manifesto could.

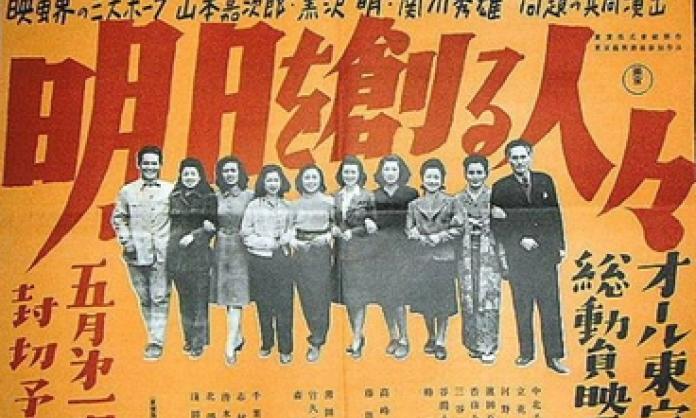

Entirely made on company time, 1946’s Those Who Create Tomorrow was, according to co-director Kurosawa, the product of democratic deliberation and intended as both a celebration of the workers’ unionisation effort and an argument for how the struggle of the oppressed can inspire others. Hirano points out that the film’s central characters are not the usual flashy stars but the forgotten workers behind every film—notably featuring a working-class woman protagonist. “Only the company is making money… they never think about our audiences”, a low-level technician says, “we want to make good movies, but the fighting spirit should be shared”.

Nor was it just socialist workers enthused by the products of democratic control over cinema: Kinema Junpo, the premier Japanese film criticism magazine, would rank six Toho films in its top 10 movies for its 1947 awards.

But while democratic control of film production led to an increase in the quality of films and the well-being of the producers and consumers, it was a disaster for the bosses.

Workers were calling the shots, with executives relegated to paying the bills and salaries. Hirano notes that budgets on some projects were exceeded by almost 200 percent.

Throughout 1947, it became increasingly clear to the Japanese bosses and US political authorities that coexistence with the Struggle Committees was untenable. Class confrontation became inevitable as high wages cut into profits and workers challenged the orders of their bosses.

Since Toho’s output was cultural and therefore not central to the functioning of the economy like other similarly militant sectors, they were the perfect first target for a capitalist counter-offensive.

The company allegedly encouraged the creation of an anti-communist scab union, Shin-Toho (or New Toho), to exploit the deeply held prejudices of actors from upper-class backgrounds. These scabs, Hirano writes, were “troubled by the way in which normally capable, friendly, and quiet employees were transformed into aggressive, polemical demagogues who stirred their listeners with militant rhetoric”.

This scab union was offered its own studio and, combined with other split-off groups, eventually reached two-thirds of the size of the original union. Pressing their advantage, bosses began a “restructuring” of the Toho company. In April 1948, they sacked more than one-sixth of the workforce on charges of being “suspected communists” and locked out the workers.

Workers reacted with a strike and an immediate occupation of the studio, opening it to friendly unionists and socialists. Hirano details life behind the barricades for the two months the occupation held firm: “[D]ance parties were held, the “Internationale” was sung, and group discussions and demonstrations were conducted inside the studio itself”.

However, the Japanese Communist Party, the most significant force in the workers’ movement, had effectively abandoned the tactic of workers’ control by 1947. Moore summarises the argument of the leading faction of the party: “If Japan was expected to follow the parliamentary road to socialism, rather than see the early establishment of a people’s republic, then neither extra-legal revolutionary bodies like soviets nor illegal workers’ takeovers of enterprises through production control could have a role.”

Counting on the unwillingness of the Communist Party to defend its rank-and-file membership in Toho, on 19 August 1948, the Tokyo district court handed down an eviction order to break the strike.

Even the most politically advanced Toho workers did not expect the strike-breakers to be accompanied by US tanks. Without a response from the broader workers’ movement, which deferred to the Communist Party, the Toho workers were isolated.

By the 1950s, Struggle Committees in Tokyo had been crushed. Moore marks the outcome of the Toho battle as a precedent-setting “test case” for the bosses’ wider campaign to regain control over industry. The smashing of such a high-profile stronghold demoralised the union movement nationally, leading many workers to lose confidence in their collective power.

Most leading militants were loyal to the Communist Party. There was no organisation of experienced worker activists capable of unifying the workplace-based committees into combined political organisations—workers’ councils—which could contest the dominant capitalist institutions.

The Toho workers were not just fighting for better films; they were fighting against the dictatorship of bosses and government departments in all spheres of life. The collective culture they built lives on through their influence on cinema but can only be properly honoured, and hopefully realised in full, through the continued struggle for a better, more beautiful world.