The global economy has been in turmoil since the start of the pandemic—collapse, rebound, inflationary spiral. Now, “It’s the ‘Godot’ recession”, Ray Farris, chief economist at Credit Suisse, told the Wall Street Journal in early March. Everyone waits but it doesn’t seem to come. Every few months, economic forecasts flip from contraction to slowdown to cautious optimism about sustained growth.

It seems like no-one knows exactly what is going on. But there are some things we do know. The advanced economies are slowing. The world is riddled with debt. The rich are getting richer. More people are going hungry. Economic tension between the world’s superpowers is threatening a new era of military conflict, and climate change is already wreaking havoc on markets. The following five charts provide a snapshot of the global economy today.

Inequality

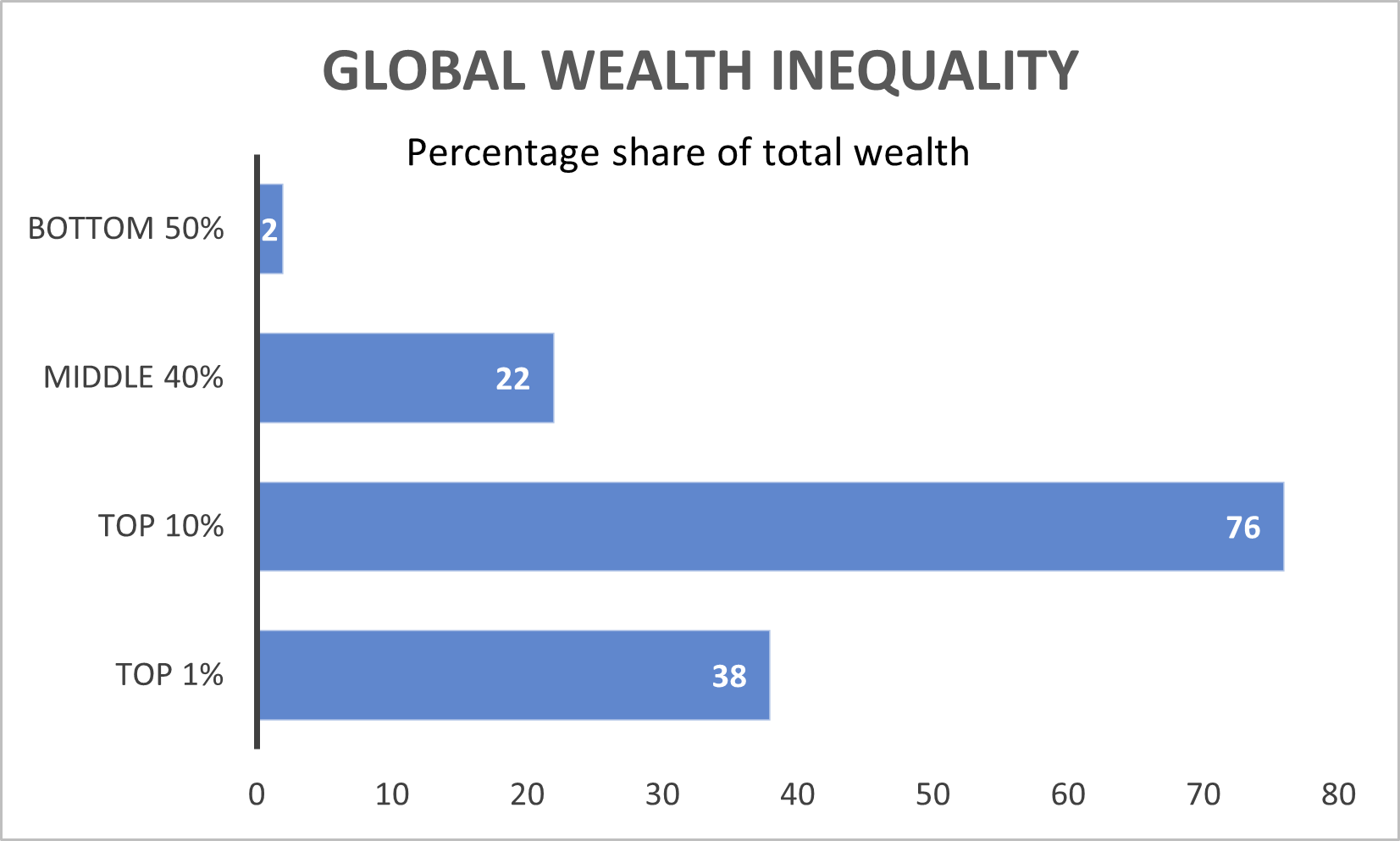

Never before has so much money been concentrated in the hands of so few people. The world’s richest 1 percent own nearly 40 percent of global wealth, according to the latest research published by the World Inequality Lab. That 1 percent has seized almost two-thirds of all wealth created in the last three years, nearly twice as much as the bottom 99 percent.

Last year ushered in stormier seas for the uber-wealthy: US$1.4 trillion was wiped from the fortunes of the 500 wealthiest on the Bloomberg Billionaires List. Some was self-inflicted (such as Elon Musk’s Twitter takeover), some was the consequence of Western sanctions against Russian oligarchs, and some resulted from stock valuation collapses in the tech industry (Mark Zuckerberg’s wealth plunged by $71 billion, a 57 percent loss).

But the losses were far from uniform. Energy companies reported record profits after the spike in oil and gas prices. Bernard Arnault, chairman and CEO of luxury goods conglomerate LVMH, rose to the top of the Forbes Rich List in December as the global luxury market grew by 22 percent.

The real losers continue to be most people on the planet. Half live on less than US$6.85 a day, according to the World Bank. And while the 2,000 or so billionaires are increasing their wealth by US$2.7 billion per day, according to Oxfam International, working-class living standards are being cut across the globe as wages fail to keep pace with inflation.

Hunger

There is more than enough food for everyone on the planet. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that the per person volume of food produced has increased by nearly 50 percent in the last 60 years, from fewer than 2,200 calories per day to more than 2,900. (The recommended daily caloric intake is between 2,000 and 2,500.)

Yet more than 800 million people are undernourished. In 2020-21, the number of people affected by hunger jumped by 150 million, according to the World Health Organisation. Almost half the world’s population can’t afford a healthy diet, and an estimated 45 million children under the age of 5 suffer from “wasting”, the deadliest form of malnutrition.

This was before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine increased food prices last year. The disruptions to global supply chains during the first years of the pandemic led to a steady increase in food prices. But when Russian tanks rolled across Ukraine’s borders last February, food prices jumped by another 20 percent.

An already acute hunger crisis in sub-Saharan Africa was made dramatically worse. In drought-stricken Kenya, which imports 90 percent of its wheat from Russia and Ukraine, the average price for a kilogram of maize doubled in just a few months.

The various climate catastrophes that ravaged parts of the globe last year pushed food prices even higher. In Australia, the cost of fruit and vegetables increased by almost 20 percent following relentless flooding along the east coast. Extreme floods in Pakistan damaged 80-90 percent of crops and raised prices three- to five-fold.

The worst hit countries are suffering horrendous consequences. In Sri Lanka, food, fuel and other basic commodities are scarce. Poverty has become the norm in Lebanon, with 80 percent of the population now considered poor, according to a UNICEF report. An estimated 2 million Zambians (10 percent of the population) are experiencing severe food insecurity.

Debt

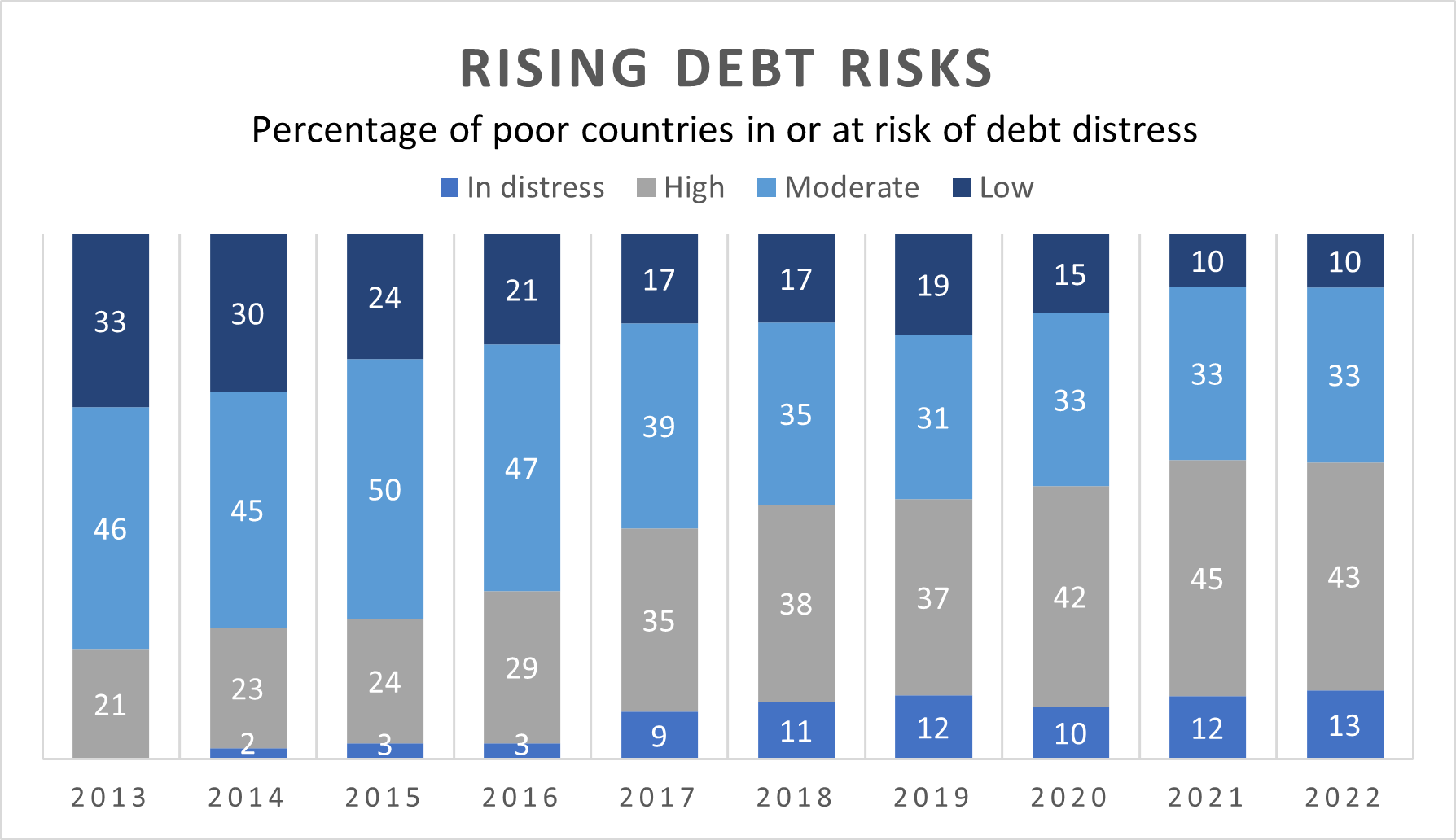

Never before has the world been so indebted. Debt grew from 230 percent of global economic output twenty years ago to 355 percent in 2021, nearly US$300 trillion, according to the Economist magazine.

Sixty percent of the world’s 75 poorest countries are at a high risk of debt crisis, according to the International Monetary Fund—and the number has doubled in less than a decade. Sri Lanka and Zambia defaulted on their debts last year, following Suriname in 2021 and Zambia, Lebanon and Argentina in 2020. At least a dozen more are teetering on the brink, including Pakistan and Egypt.

The combined business, household and government liabilities of 30 large low- and middle-income countries are now US$98 trillion, up from $75 trillion four years ago, according to the latest edition of the Global Debt Monitor, published by the Institute of International Finance.

In 2022, inflation and rising interest rates increased the value of debt interest bills by 35 percent, according to the World Bank. The poorest governments now spend more than 10 percent of their export revenues on debt servicing.

Lethargy

At first glance, the global economy seems to be roaring ahead with new inventions and sophisticated technologies: electric vehicles and self-driving cars, folding smartphones, satellite internet, precision drones and automated everything present an image of a futuristic world made possible by advances in artificial intelligence and microchips.

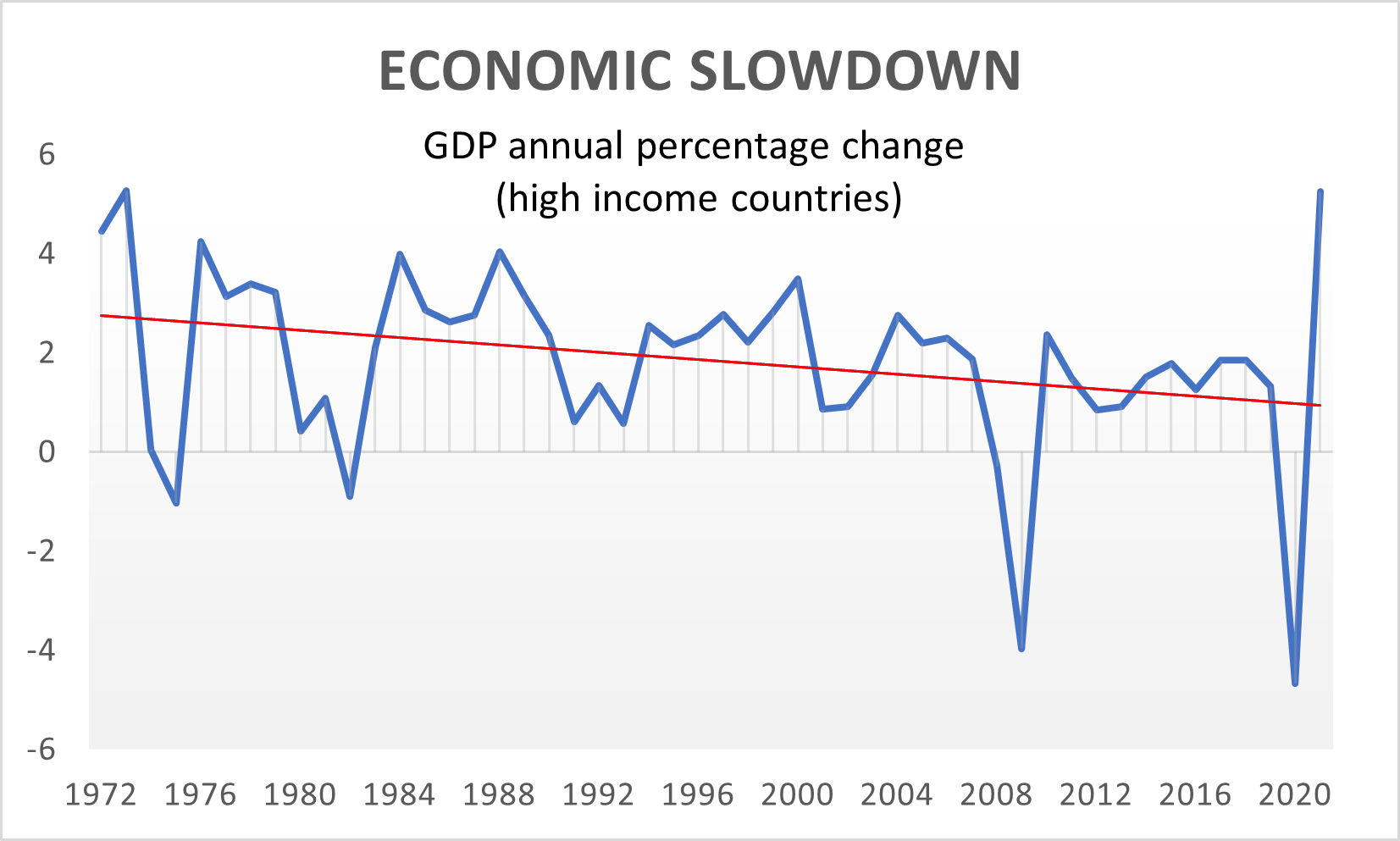

But looks can be deceiving. Capitalist economic growth has slowed decade after decade in the most advanced economies. In the 1960s, annual economic growth in the OECD (basically a club of Western nations) averaged around 5 percent—in the 2010s, it was more like 2 percent.

Most economic commentary compares the present to the immediate past—last month or last year. Long-term trajectories are rarely discussed. But this trend slowdown forms the backdrop to the ups and downs of the economy today: advanced capitalism lost dynamism in the 1970s and hasn’t been able to get it back.

The recessions have trended deeper, the recoveries have tended to be weaker, and governments, businesses and households have increasingly turned to debt to stay afloat. This all makes for a more volatile, crisis-prone environment.

Imperialism

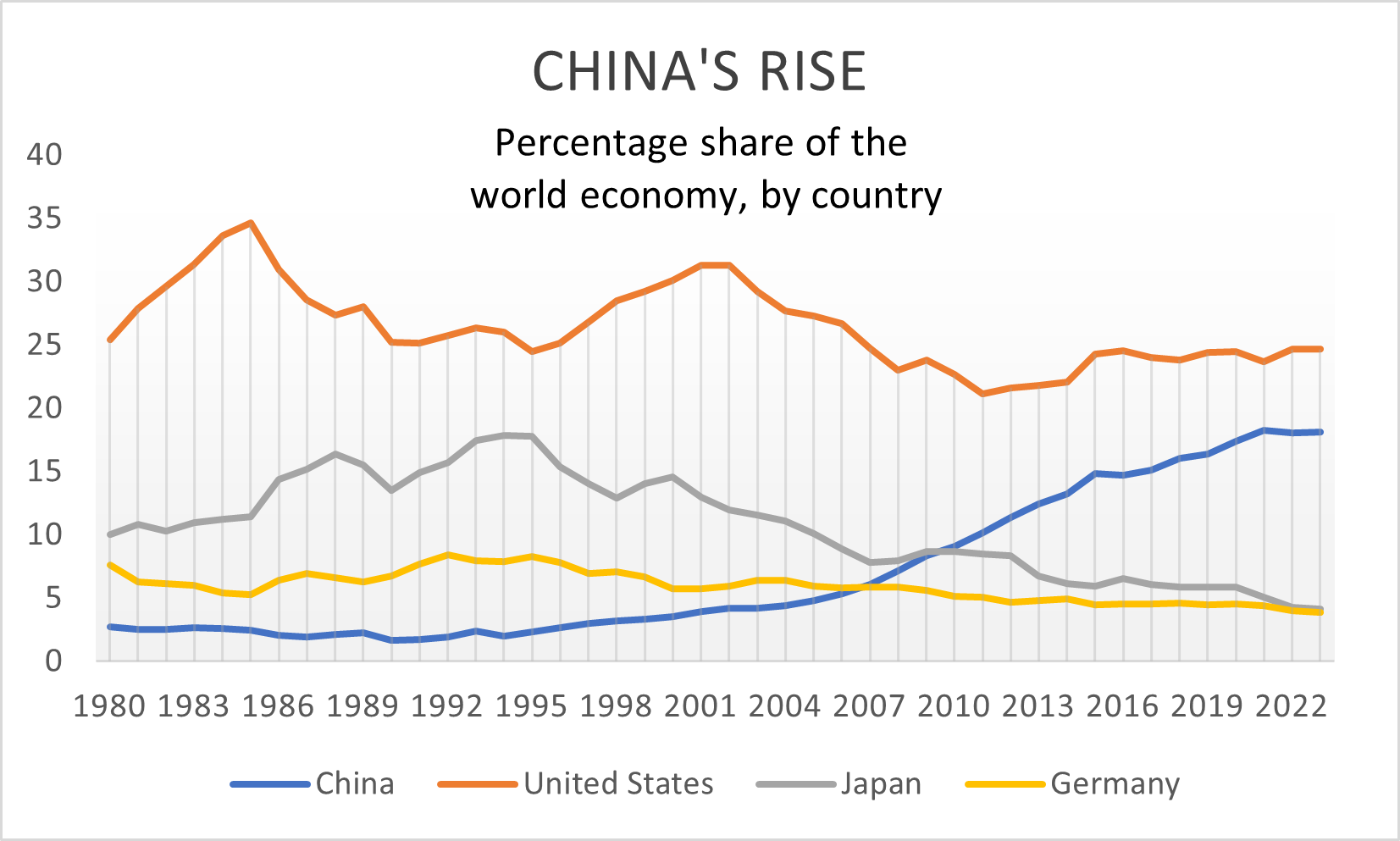

For 70 years, US economic influence has stretched to every corner of the globe through a system of international finance and global supply chains. It has never faced a serious economic rival. Until now. Twenty years ago, China made up only 5 percent of the global economy; now it is closer to 20 percent—the most rapid and dramatic shift in history.

“When [economic] competition has finally reached its highest stage ... then the use of state power, and the possibilities connected with it, begin to play a very large part”, Russian Marxist Nikolai Bukharin wrote more than 100 years ago in Imperialism and world economy.

“The state apparatus has always served as a tool in the hands of the ruling classes of its country, and it has always acted as their ‘defender and protector’ in the world market; at no time, however, did it have the colossal importance that it has in the epoch of finance capital and imperialist politics ... The significance for capitalism of high tariffs ... must increase still more; the various forms of ‘protecting national industry’ become more pronounced; state orders are placed only with ‘national’ firms ... the activities of ‘foreigners’ are hampered in various ways.”

He could have been writing about today. The US government has in recent years openly referred to China as a strategic competitor, instituting a range of protective tariffs, restricting China’s access to advanced microchips, banning and sanctioning Chinese telecommunications firm Huawei and providing hundreds of billions of dollars in state subsidies to draw capitalist investment away from East Asia and back to America.

The economic war between the two countries may well spill over into a shooting one. The history of imperial rivalry has eventually been a history of terrible military conflicts. Taiwan is a possible battlefield, and all the world’s major powers have launched rearmament drives.