In the history of protest, there are some events that tower above the pack, both in their impact on society, and on the lives of those who participate in them. The 11-13 September 2000 blockade of the World Economic Forum’s Asia-Pacific Economic Summit, held at Melbourne’s Crown Casino complex, is one of them.

The scale of resistance and determination shown by the estimated 20,000 people who showed up on the morning of 11 September, facing down thousands of police to successfully shut down a meeting of some of the world’s most powerful and wealthy people, is something that won’t quickly have faded from the memories of those who witnessed it. Australia arguably hasn’t seen a moment of mass defiance so hopeful and inspiring in the twenty years since.

The major global crises and injustices that S11 (as, in the fashion of the global anti-capitalist movement of the time, the blockade was known) sought to foreground are still far from being addressed. If anything, the situation for the mass of the world’s workers and the poor has only worsened in the decades since. According to Oxfam, the world’s richest 26 individuals are worth more than the poorest half of the world’s population combined. The scale of the destruction of the human and natural world being wrought in the name of big business profits has only grown, and neoliberalism remains the economic worldview of a political class determined to serve its corporate masters to the end.

S11’s organisers ran an online poll that voted for John Farnham’s 1986 pop hit “You’re the voice” as the anthem for the blockade. Farnham’s management was furious and demanded that his image, and a link to download the song, be removed from the S11 website. The choice was, of course, partly ironic. But Farnham’s lyrics, nevertheless, capture something of the optimistic (and one might say, given what has happened since, innocent) spirit of the movement: “This time, we know we all can stand together; With the power to be powerful; Believing we can make it better”.

A lot has changed in the past twenty years. One thing that hasn’t, however, is that when enough people stand together against injustice, we have a power that can shake our rulers to their core. And that is something that, in the darkness we’re currently living through, we can all do with being reminded of. It’s worth looking back on S11 then, not simply as an act of remembering and a contribution to the “historical record” of protest in Australia, but as a spur to the imagining, and the carrying out, of the kind of resistance we need to the destructive juggernaut of global capitalism today.

● ● ●

The World Economic Forum (WEF) was formed in 1971. It is known mainly for its annual January summit in the luxury mountain resort of Davos, Switzerland, and describes itself as engaging “the foremost political, business, cultural and other leaders of society to shape global, regional and industry agendas”. At the time of the S11 protest, the WEF had 968 member organisations, among which were many of the world’s richest and most powerful corporations.

The decision to blockade the meeting of the WEF’s summit in Melbourne didn’t come out of nowhere. The period from 1999 to the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks in the US was the height of what was variously known as the global justice, anti-globalisation, or anti-capitalist movement (calling it the “anti-globalisation” movement, as many did at the time, was misleading—one of the movement’s main slogans, after-all, was “globalise resistance”). The origins of the movement were the late 1980s and early 1990s, a period in which the US tried to cement the global hegemony it enjoyed following the collapse of the Soviet Union by rewriting the rules of global trade to the benefit of US corporations.

1994 was a milestone year. In Mexico there was the Zapatista rebellion—an uprising of peasants and rural workers mainly of Indigenous Mayan background. The Zapatistas launched their uprising on 1 January, the day the North American Free Trade Agreement between Canada, the US and Mexico came into effect. In the same year, there was a significant mobilisation in Europe targeting the 50th anniversary celebration of the formation of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank in Madrid. From this point on, protests targeting these and other major institutions of global capitalism became a regular occurrence.

1999, however, was when the movement really took off. On 18 June, there was a “global carnival against capital” in London, timed to coincide with a meeting of the G8 taking place in Germany. The main slogan for the J18 protests, as they were known, was “our resistance is as transnational as capital”. Thousands of protesters marched on London’s financial district, fighting with police throughout the day.

The main precursor and inspiration for the S11 blockade was, however, the “Battle in Seattle”—the blockade and mass protests targeting a meeting of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in November 1999. There are a number of reasons why this event took on such importance for the left internationally. First, it took place in the centre of global capitalism. Second, the protest eclipsed all previous efforts of the anti-capitalist movement. At its height, more than 50,000 people were involved.

As well as the blockade of the WTO meeting, several marches each with thousands of participants converged on the venue. This included a student march, a “third-world citizens” march, and a march of tens of thousands of trade unionists. Delegates trying to get into the meeting were confronted and turned back by the blockaders. The WTO’s “opening ceremony” had to be cancelled.

The US and international media flew into a fury. Protesters were described as savages bent on the destruction of society. This paved the way for a vicious police crackdown. The scenes that followed became a defining moment, with the police drowning the blockade in a cloud of teargas and beating back any further resistance with truncheon blows. Hundreds of activists were rounded up and arrested.

All this, however, only galvanised activists who were watching events unfold on TV and via the Independent Media Centre established in Seattle to provide real-time online reporting from those on the ground (something that was then very new, and which inspired the rapid growth of a network of Indymedia websites around the world). The tactic of blockading the summit, of physically preventing access by delegates, had worked. The destructive “business as usual” of the WTO had been halted, and a new spirit of resistance spread around the world.

● ● ●

Organising for the S11 blockade began in the early months of 2000. The main groups involved were the S11 Alliance—made up of representatives from various socialist groups, trade unions, student unions and environmental organisations such as Friends of the Earth—and the Autonomous Web of Liberation (AWOL), which, as the name suggests, brought together individuals and groups (including the pithily named “Angry People”) committed to the principles of autonomous organising. In the weeks leading up to 11 September, meetings of each attracted between 100-200 people.

Divisions between the far-left groups involved threatened, briefly, to derail the entire project. As Jeff Sparrow and Jill Sparrow relate in their 2004 book Radical Melbourne 2: The enemy within, “The first anti-WEF organising meetings drew sizeable numbers, but discussions stalled amid such acrimony that ASIO agents in attendance speculated as to whether a rival security force might be deliberately sabotaging proceedings”. As momentum grew, however, the left managed, largely, to put internecine rivalries aside and get on with the job of building the blockade.

Teach-ins and activist training sessions proliferated. One, hosted by the S11 Alliance on 28 May, included an eyewitness account from the “Battle in Seattle”, and sessions on the environmental impact of multinationals, women and globalisation, and third-world debt.

At the time, I was a student at the University of Melbourne. There, in the winter of 2000, a battle raged between left-wing students and the conservative leadership of the student union—members of the right-wing Labor Unity faction. The latter put a ban on student union funds being used for S11 organising. In response, the left called a student general meeting, which was attended by more than 300 and which voted to censure the student union leaders and then marched on the union offices. Melbourne’s Herald Sun reported on the meeting on 1 September under the headline “Student union head flees protest anger”.

The media, in fact, played a significant part in publicising the blockade. Not out of any sympathy for the cause, but because after Seattle, hysteria about the possibility that such violent scenes might be repeated in Australia sold newspapers. The Murdoch Press led the charge. The 8-9 July edition of the Weekend Australian put the movement on the front page of its “Review” section, with a picture of a black-clad and gasmask-wearing anarchist standing in front of a wall of flames, and the headline: “Fights, cameras, activists: The protest movement still burns with the fire of Seattle, Melbourne and Sydney are next on the agenda”.

Most mainstream commentators thought it absurd that anyone would see legitimate reason to protest against the WEF. The Herald Sun declared that those planning to blockade the Summit were an “army of mindless radicals ... hell-bent on forcing their ill-considered views on others more enlightened than themselves”. The most frothing-at-the-mouth conservatives, such as Andrew Bolt, saw a communist conspiracy afoot. When a number of more respectable organisations, such as the Victorian Council of Social Service and Trades Hall, lent their support to S11, Bolt declared: “These wide-eyed innocents are what Russian dictator Vladimir Lenin dubbed the ‘useful idiots’ of communist revolutionaries—revolutionaries who in this case are veterans of protests which have injured some 200 police”.

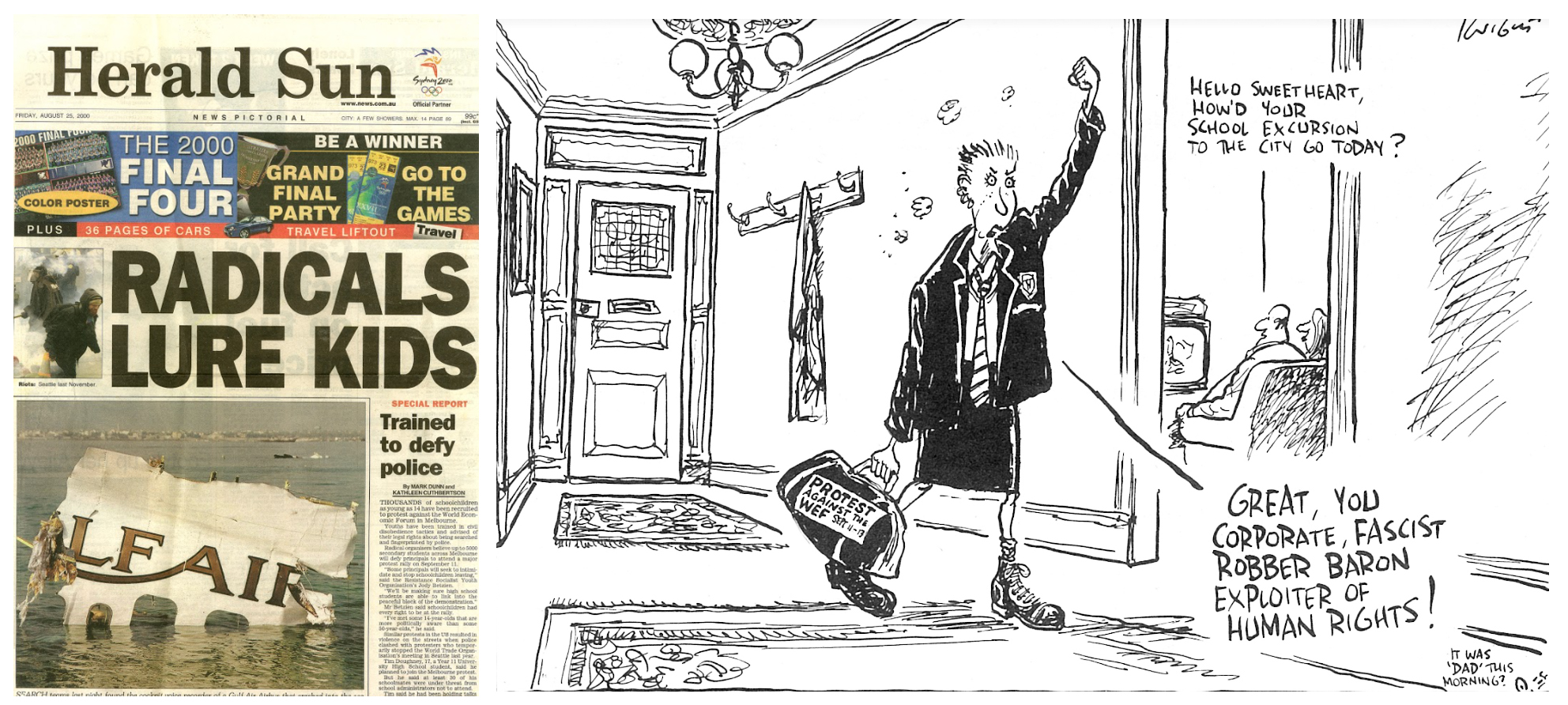

A particular point of interest for the media was the possibility that significant numbers of high school students might get involved. The Herald Sun reported on this as early as 18 July, Keith Moor writing: “Radical groups are recruiting schoolchildren for what is expected to be one of Melbourne’s biggest protests”. The real clincher came two weeks before the summit, on 25 August, when the paper put out a front page with the screaming headline “RADICALS LURE KIDS”. In the accompanying article, Mark Dunn and Kathleen Cuthbertson breathlessly reported: “Thousands of schoolchildren as young as 14 have been recruited to protest against the World Economic Forum in Melbourne. Youths have been trained in civil disobedience tactics and advised of their legal rights about being searched and fingerprinted by police”.

Another piece, published in the Australian on 28 August under the headline “Children of the revolution”, reported on a training camp organised by the S11 High School Affinity Group, where “students heard about revolutionary luminaries such as Che Guevara, Fidel Castro and black US militant Malcolm X, and were taught how to prevent breaches in blockades, how to avoid crowd control efforts and how to deal with being arrested by police”.

Murdoch’s editors were so cloistered among the wealthy elite as to assume that anyone reading the reports would be appalled. It didn’t occur to them that many people, and particularly many young people, would be inspired by the idea of shutting down a meeting of the rich and powerful and would propel them into joining the action on the streets. Whatever their intention, the effect was to supercharge the campaign beyond anything that could have been achieved by the efforts of the S11 organisers alone.

● ● ●

In the lead-up to the blockade, it seemed clear something big was going to happen. The police mobilisation was massive. On the weekend before the conference (11 September was a Monday), they erected an imposing, three-metre steel and concrete barrier around the perimeter of the Casino, leaving only a few entrances at strategic points. The front page of the 11 September edition of the Herald Sun screamed “FORUM FORT” and reported on preparations including the mobilisation of 2,000 police to enforce a “protest exclusion zone” around the venue. Their preparations, however, came to nought. If anything, the police barricades assisted blockaders by limiting the ground we had to cover to prevent the entrance of delegates.

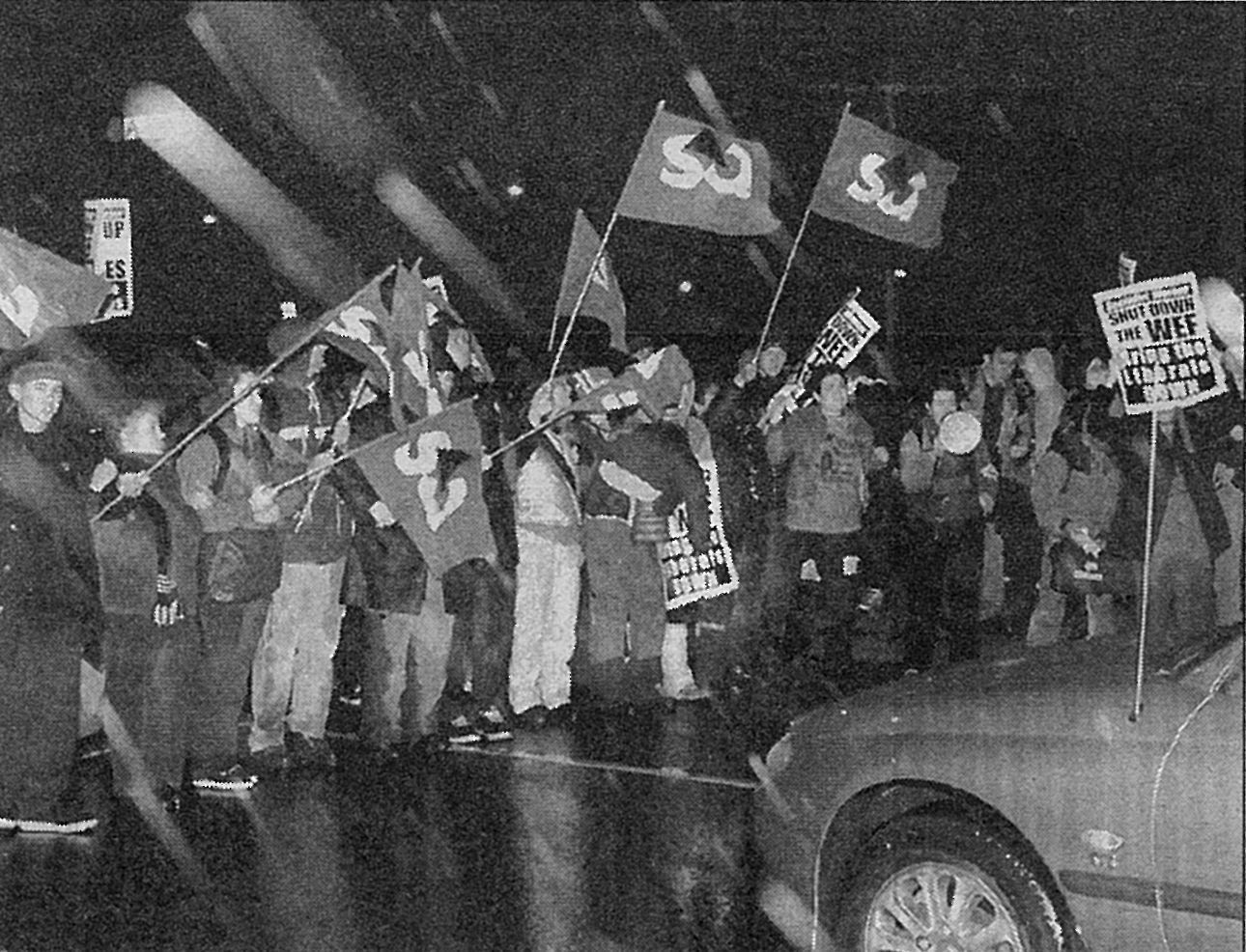

On 11 September, the action kicked off well before dawn. The Melbourne weather put on a suitably dramatic show, with a blustery spring cold front sweeping through just as attendees began assembling in front the Casino on Queens Bridge Street. Rain pelted down and the temperature plummeted as blockaders began marching into the surrounding streets.

The immediately striking thing was the sheer number of people who came prepared to take direct action to shut the summit down. By the time the first delegates attempted to enter the Casino, many thousands had already assembled, blocking all the gaps in the barricades where police had intended to usher them through. As the morning progressed, thousands more protesters arrived—estimates of the total attendance for the day settling on the figure of 20,000. Police were caught off guard. They were in a state of disarray, attempting to break the blockade in an ad hoc basis as buses of delegates and individual luminaries arrived.

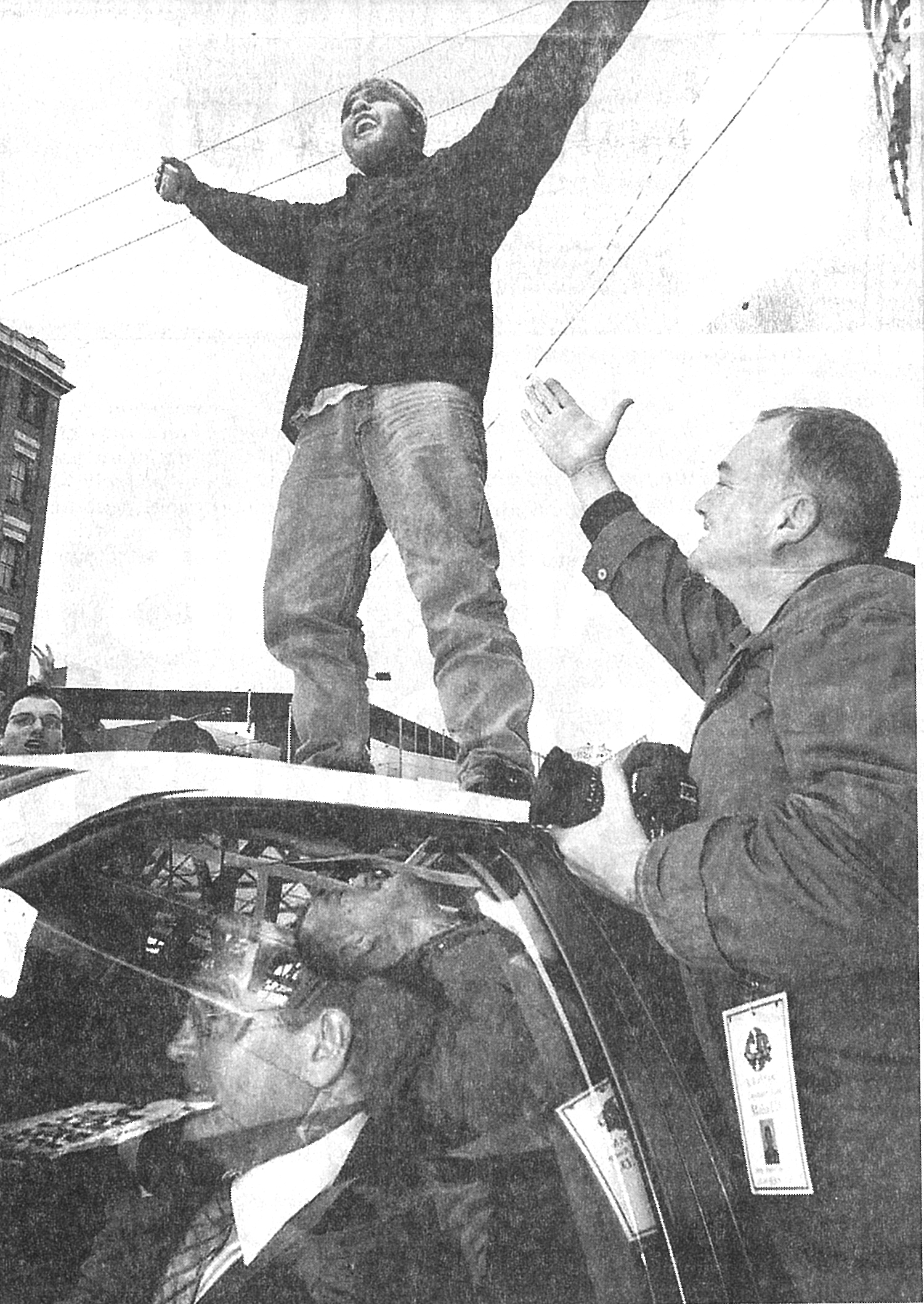

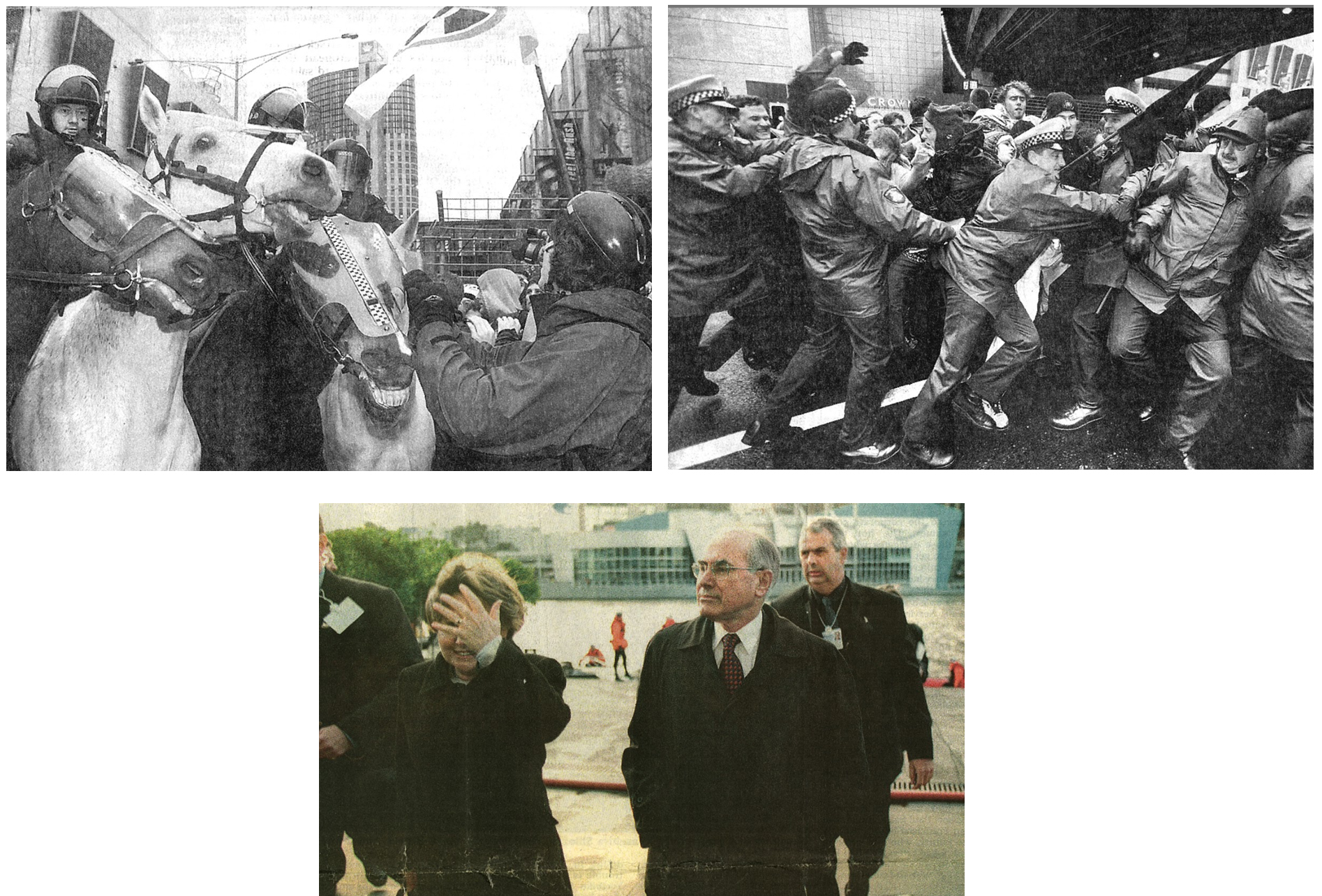

The Liberal premier of Western Australia, Richard Court, who had recently introduced mandatory sentencing laws that disproportionately impacted Indigenous people, had his driver attempt to take him to the Clarendon Street entrance of the Casino. The car was quickly surrounded by hundreds of blockaders, and for the next hour or so Court was stuck fast. In what became one of the defining images of S11, Indigenous activist Ivan Wyatt-Ring spent much of that time on the roof of the car, shouting at Court: “This is what you’ve been doing to my people!” Court was freed only with the intervention of hundreds of police, who charged their horses into the crowd and followed up with batons.

Similar scenes played out around the Casino. Only about a third of delegates managed to get through the blockade. The Victorian Liberal Party opposition leader, Denis Napthine, later complained that he managed to enter only by scrambling over one of the barricades erected by police. Others, such as Prime Minister John Howard, were ferried across the Yarra River on boats. An article by Jon Hilsenrath, published in the Wall Street Journal on 12 September, recounts the experience of a group of conference delegates who boarded one of a number of buses intended to transport attendees into the Casino:

About halfway through a gruelling three-and-a-half-hour bus trip Nestle SA executive Dave Parker started getting stir-crazy. ‘I feel like a goldfish in here’, he muttered to the 40 or so international businessmen travelling with him. No wonder. The trip was supposed to take more like three-and-a-half minutes. Mr. Parker, visiting from South Korea ... was simply trying to take a shuttle bus from the Sheraton Towers Hotel to Crown Towers Hotel, about 300 meters away, to attend a session on the challenges of the global economy. Instead, he met one of the challenges face to face, in the form of thousands of protesters rallying against globalization.

The bus attempted several times to break the blockade. Finally, the delegates were taken to the banks of the Yarra, where they were to board speed boats. Even this failed when blockaders gained wind of the plan and surrounded them once again. Finally, four hours after they first got on the bus, the hapless executives were delivered back to their hotel.

By early afternoon, it was clear the blockaders had achieved victory. As in Seattle the previous November, the power of ordinary people standing together in numbers proved, at least temporarily, to be more than a match for the forces of order who had promised to ensure the smooth running of the summit at all cost.

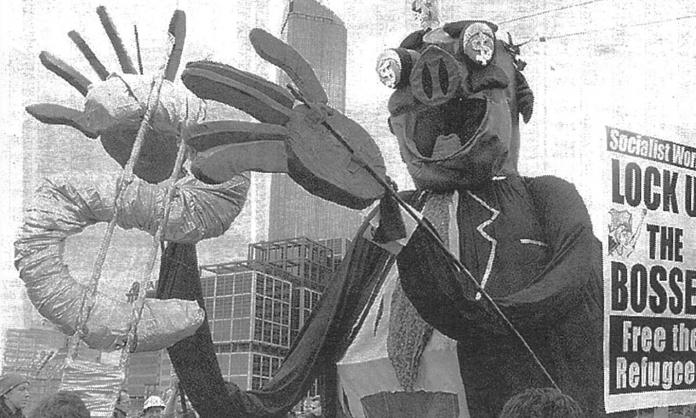

At this point, the mood turned more festive. Those arriving, such as the hundreds-strong high school student contingent that marched from Flinders Street Station to Crown Casino around lunchtime, stumbled on a joyous scene. “Music played from a stage near the river bank, while on the barricades, every variety of socialist stood shoulder to shoulder with costumed harlequins and stilt-walking street performers”, recalled Jeff and Jill Sparrow. “Graffitists adorned the Southbank concrete with a mixture of the profane and the profound, and a skinny boy in his school uniform held a sign proclaiming: ‘Wesley students against class privilege’. Unionists in their blueys joined forces with the Monsanta Claus, a troupe of anti-corporate Father Christmases.”

For the Victorian government, led by Labor Premier Steve Bracks, it was a major embarrassment. It had hoped that the summit would put Melbourne on the map as a major centre of global capitalism. Instead, it appeared to be a centre of global resistance. In the news that night, Bracks joined the almost unanimous chorus of Australia’s political and media elite denouncing the blockade in the strongest terms. The behaviour of protesters was, Bracks said, “un-Australian” and “fascist”.

Conference organisers and the right-wing media were baying for blood. For its 12 September edition, the Herald Sun ran with the headline “SHAMEFUL”, saying: “Ugly protests forced Crown Casino to shut last night as the World Economic Forum was held hostage to violence”. The paper spoke to Richard Court, among others, who complained: “It was that typical mob mentality ... It’s very un-Australian”. Police got the message loud and clear. A note in the police log recorded following a meeting with conference organisers and Bracks on the evening of 11 September said: “Breakfast tomorrow delegates to leave hotels by 0700 to be at Crown by 0715 by whatever force necessary”.

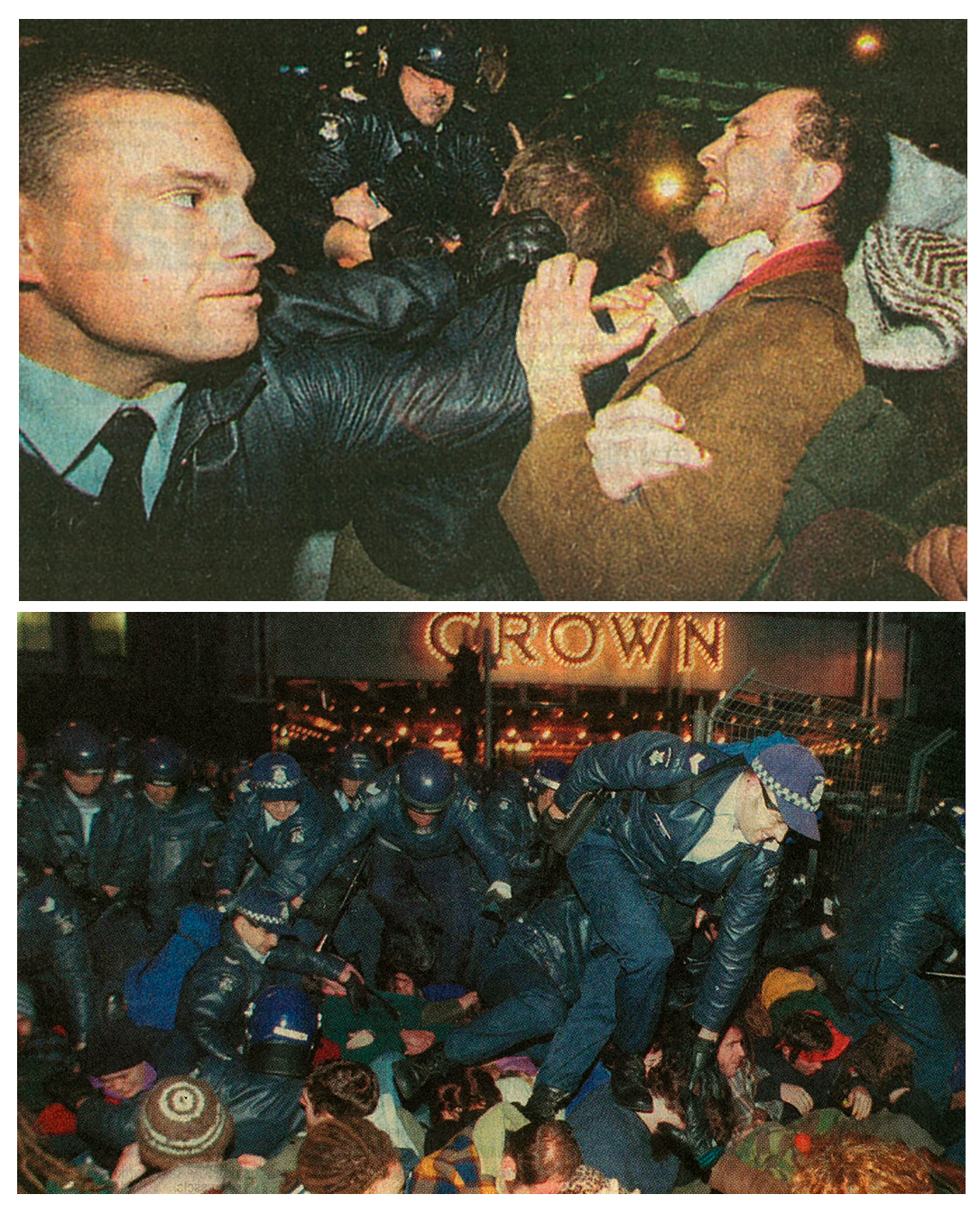

The mood in the morning of 12 September, as blockaders once again assembled at the main entrances to the Casino, was tense. Shortly after sunrise, a blockade on Queens Bridge Street was savagely attacked. Hundreds of police moved in with batons from behind, trampling and clubbing anyone who resisted. Tens of police on horseback moved in at the same time, cordoning off the intersection while any remaining blockaders were dragged away. Shortly afterwards, a convoy of buses carrying delegates entered the Casino.

That night, after a largely uneventful day that included a march of thousands of trade unionists in solidarity with the blockade, police repeated the performance. This time, the level of force deployed was more extreme. The blockade was stronger than it had been in the morning, and the police climbed the barricades and batoned people from above. Hundreds required medical attention. Some were seriously injured and had to be taken away by ambulance.

The conference organisers welcomed this violent restoration of order. “The police action was excellent”, said WEF founder Klaus Schwab. “They gave the protesters a chance on the first day to behave in a civilised way, they charged when it was necessary to restore law and order.” Politicians, too, were effusive. In response to allegations that the use of force was excessive, Bracks declared the blockaders “got everything they deserved” and went so far as to promise to hold a BBQ with police to thank them for their efforts.

Their assumption (as in the lead-up to the protest), was that the majority would be behind them. This, however, wasn’t the case. An early sign came the next day, on 13 September, when the blockaders came together for a final triumphant march through Melbourne’s CBD. As the crowd of several thousand snaked its way along the city streets, many pedestrians, office workers and others stopped to cheer. That night, the news included footage of a reporter interviewing people whose cars were held up by the protest. Most were in favour of the blockaders, saying variants of “of course it’s inconvenient for me, but I support the broader cause”.

● ● ●

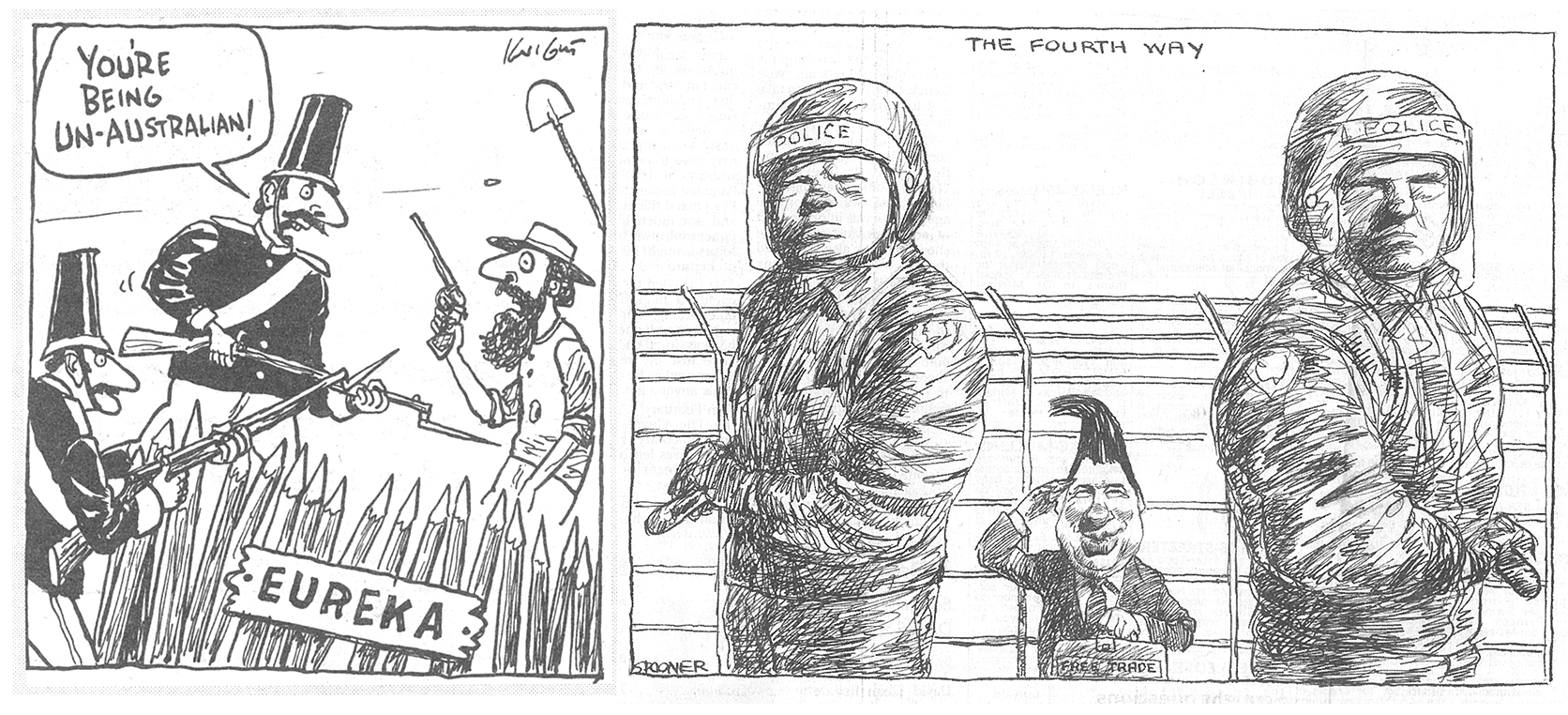

In the following weeks, there was a backlash against Steve Bracks. Many were shocked that the Victorian Labor leader, who was elected premier only the year before in an upset win against neoliberal stalwart Jeff Kennett, would so stridently come out in support of the violent police repression of protesters standing against global inequality and injustice. His claims that the protesters were “un-Australian” and “fascist” were widely ridiculed. A cartoon by the Herald Sun’s Mark Knight—not generally known as a radical—depicted a participant in the Eureka rebellion (a defining moment in Australia’s national mythology) being threatened with a bayonet by a soldier and told “you’re being un-Australian!”. John Spooner in the Age depicted Bracks under the heading “the fourth way”, standing behind two giant baton-wielding police officers, saluting and clutching a briefcase labelled “free trade”.

At least twelve ALP branches, including his own in Williamstown, passed motions condemning Bracks, as did the Victorian Trades Hall Council executive. Paddy Garrity, who was present at a meeting of the Williamstown branch where Bracks spoke, told the Herald Sun that the premier “said he made an error of judgement, particularly in calling the protesters fascists and saying they got what they deserved, but he didn’t apologise”.

For a period, Bracks even faced the possibility of a formal censure motion being put to the state Labor conference, held in late October. Inside the venue, one Labor member held a banner that read “ALP Yes, Jeff Bracks No” as Bracks gave his speech (referring to him as “Jeff Bracks” highlighted the continuity between him and his predecessor Jeff Kennett). Typically, however, efforts to put the motion were blocked by the party’s dominant right-wing faction.

Bracks did receive something of a comeuppance. On 21 October, during a ceremony celebrating the opening of the Melbourne Museum, the premier received a cream-pie flush in the face from Marcus Brumer, an S11 activist who told reporters he “wanted to make a political statement about how strongly I felt about people having their bones broken and being viciously assaulted by police”.

● ● ●

What happened to the anti-capitalist movement after S11? In Australia, it proved fleeting. Efforts were made to keep the spirit of mass rebellion alive. In Melbourne, there were regular Friday night blockades of Nike’s flagship store on the corner of Bourke and Swanston streets, highlighting the company’s use of sweatshop labour in underdeveloped countries. There was also a national mobilisation for “M1” on 1 May 2001, targeting stock exchanges and other symbols of capitalism in cities around Australia. None of this, however, reached anywhere near the scale of what had occurred outside Crown Casino.

Internationally, the movement continued to gain momentum. There were major anti-capitalist mobilisations in Prague later in September 2000, targeting a meetings of the IMF and the World Bank, in Quebec in April 2001, targeting a Summit of the Americas meeting, and, most significant of all, a 300,000-strong convergence on the G8 summit held in the Italian city of Genoa in July 2001.

The whole thing was brought to a crashing halt, however, by the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks in the US. It’s a sign of the impact of S11 that, when the 9/11 attacks occurred, the coincidence of the date led some to believe there was a connection between the two, and a number of Australian reporters are known to have questioned S11 activists about their possible involvement. The reality, however, is that the attacks were a major blow to the movement, one from which it would never recover.

The scenes of devastation in New York and Washington changed the political terrain overnight. For the next few years, the question of war dominated: first the invasion of Afghanistan, then the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Many of those who had formed the backbone of the anti-capitalist movement internationally were disoriented by this. The main target of the movement was “corporate globalisation”. Particularly for the autonomist currents, questions of state power and of imperialism had seemed increasingly irrelevant to a world in which, they thought, multinational corporations, rather than states, were the main actors.

The anti-war movements of 2001-03 mobilised many more people than the anti-capitalist movement had, but on a quite different, and politically more limited basis. Some in the anti-capitalist movement were put-off by the sight of masses of ordinary people marching peacefully against war. Many took part in the marches but struggled to find their feet as activists in the new movement. As the wars dragged on, the historical moment of anti-capitalism faded, and many people simply drifted into inactivity.

Could the movement have made significant further advances if it weren’t for this change in terrain? There are reasons to be doubtful. The strategy of shutting down major gatherings of the global capitalist class had limits. One was the ability of organisations like the WEF, WTO, IMF, G8 and so on simply to move their events out of the reach of protesters. Another, hinted at by the events of 12 September in Melbourne, was the ability of the state simply to beat the movement back with increasing levels of violence.

The G8 summit in Genoa in July 2001 proved to be the movement’s apotheosis, and it brought the latter of these limitations into stark relief. The Italian police went on a rampage, killing one protester and severely injuring hundreds. Faced with the savagery of the repression, there was little people could do but flee. In the midst of this carnage, it became clear that any further advance for anti-capitalism would require a force greater than that which could be mustered by protests and blockades, no matter how many thousands, or hundreds of thousands, were involved.

That force, as socialists had argued from the beginning, was that of the organised working class. Unfortunately, the 9/11 attacks intervened before the initial, small-scale movements in this direction could be further developed.

● ● ●

What was the impact of S11 on the left in Australia? The picture is mixed. The media played a big part in making the blockade a success, but you also have to factor in the size of the organised forces involved. A profile of the main groups that comprised the S11 Alliance, published in the Herald Sun’s “RADICALS LURE KIDS” edition of 25 August 2000, gives the following membership numbers: Friends of the Earth, 4,500 members; Democratic Socialist Party (DSP), 1,000 members; Resistance (the DSP’s youth organisation), 600 members; International Socialists (ISO), 300 members; Socialist Alternative, 50 members. To this you have to add the hundreds of autonomists and anarchists associated with AWOL, the Greens, campus Queer and Environment collectives and so on.

The left today looks vastly different and (with the exception of Socialist Alternative, publisher of Red Flag, which has grown from 50 to more than 400) much smaller. The DSP and Resistance are no more—they were liquidated into the Socialist Alliance in the late-2000s, an organisation that, today, would be lucky to have more than 100 real members nationally. The ISO claimed to have recruited at least 50 people at S11, but shortly afterwards went into rapid decline, losing a large chunk of its membership in the period of the anti-war movement from 2001-03. Today, its remnants are part of Solidarity, a group with an active membership of no more than 50.

The picture is similar with the anarchists, environmentalists and activist student collectives. The Greens have long since turned away from serious involvement in radical street protests and today present themselves mainly as a respectable parliamentary alternative for progressive white-collar professionals. And the unions have continued their long march to the right, tailing along dutifully behind a Labor Party determined, it seems, to rid itself of any last remaining vestige of a commitment to standing up for workers and the poor.

The 500 or so attendance at the Melbourne blockade of the International Mining and Resources Conference (IMARC) in October last year was both a tangible indication of this decline, and an early indication of what might be possible in the coming period. The blockade was in many respects a straightforward repeat of S11. It even took place right across the road from Crown Casino, outside the Melbourne Convention and Exhibition Centre on Clarendon Street. The blockade was built in much the same way—by a “Blockade IMARC Alliance” comprising many of the same groups (or their successors) that were involved in S11. And it tapped into a widespread sentiment that more radical tactics are justified to avert an impending climate catastrophe. There was only so much momentum that could be built, however, amid the broader decline of the organised left, and without the same kind of media hysteria that greeted the anti-capitalist movement’s arrival on Australian shores in 2000.

To be able to repeat anything on the scale of S11 in the future, the left needs, above all, to be bigger and more organised. But if the history of the various groups behind S11 over the subsequent two decades shows anything, it’s that organisation alone isn’t enough.

A big part of the failure of the left to consolidate the hundreds, if not thousands, of people who were won to an anti-capitalist worldview in 2000 into something that could be sustained through the subsequent, more difficult, period, was a simple lack of patience. Alongside organisation, we need the politics to cope with the various twists and turns of history (the ability to shift from anti-corporate to anti-war campaigning is an example), we need the perspective to assess each new situation as it arises, and we need the patience and perseverance to make the most of opportunities that do exist, without losing our heads in the process.

In the coming years, there will be more, and greater, moments of resistance than the one on the morning of 11 September 2000 in Melbourne. In the past year and a half, a series of revolts have swept the world—from Sudan to Chile, Hong Kong to France, Belarus to the US. In 2000, neoliberalism was in its heyday. Today, the economic and political order that the global capitalist class and their political servants have built is crumbling all around them. Amid pandemic, economic crisis and climate disaster, the task of building a radical, organised alternative to the barbarism of global capitalism has never been more urgent.