Allyship presents itself as a way that people can show support for the rights of an oppressed group that they themselves are not a part of without “taking the space” of those who are oppressed. Marxists, conversely, argue that solidarity is the key way we can win reforms for, and ultimately liberate, the oppressed. Allyship and solidarity might sound like much the same thing, but there are important differences in these strategies for social change.

Allyship has at its heart the proposition that the experience of oppression tells us everything about how to fight oppression. Of course, the experience of oppression can be a powerful galvanising tool for activism. But experience is not the same as political analysis. Allyship assumes that those from oppressed groups are automatically and exclusively political authorities, and that therefore they must be deferred to on questions of political strategy. It holds that people without direct experience of a particular oppression are, at best, able to offer encouragement from the sidelines, or, at worst, are causing harm by “centring themselves” when campaigning against oppression.

Identities are forged by capitalism and oppression, but also by resistance to oppression. The “gay” identity was partly a product of struggle, and “Black” was used—in some parts of the world at least—as a political identification of anyone non-white who experienced racism. This is one reason why people can think identity is automatically radical.

But there is an enormous diversity of class positions, opinions and political outlooks within identity groups, which creates endlessly varied experiences and responses to oppression. How are we meant to know who to listen to in this sea of contradictory ideas? How can there be an “immutable authority” of experience if two members of the same oppressed group are arguing different things?

It’s often claimed that the most marginalised or “intersectional” groups inherently represent the vanguard of struggle and should be “centred” at all times because they win the “oppression Olympics” (an unhelpful game of one-upmanship between individuals and groups based on identity to work out who’s the most oppressed). But there is no correlation between a person’s marginality and their radicalism; “intersectional” individuals now populate even the Republican and Liberal parties.

Of course, socialists agree that in a world in which oppression makes it harder to lead, we need to encourage oppressed people in their fight. But that is not the same as arguing that being oppressed means you automatically have the most useful strategy for fighting oppression. Increasingly in activist circles, anyone who contests this political perspective is accused of “violence”.

The other side of allyship is the way in which it assesses those who are not oppressed. They are understood to walk through the world with a set of unearned privileges and, consciously or not, hold biases towards the oppressed to maintain and justify these privileges. Allyship argues that anti-Black racism, for example, comes from white people having an in-built but unconscious desire to dominate Black people. In the words of Reni Eddo-Lodge, author of Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race: “Racism is a white problem. It is a problem in the psyche of whiteness”.

Marxists have a radically different starting point: oppression is a structural phenomenon. It has been created and maintained by the ruling class to extend and fortify their power over the rest of us. The racist ideas in the heads of some white people originate from those at the top of society because bigoted ideas justify their oppression of the working class as a whole and specific identity groups in particular.

“Structural” doesn’t mean that institutions are simply made up of people with a bunch of personal prejudices. It refers to the way in which those institutions function in our society to organise and defend capitalism and maintain oppression. The race of the individuals within an institution doesn’t make much of a difference to how racist that institution is. For example, every one of the five police officers charged with the murder of Tyre Nichols in Memphis last January was Black.

Similarly, the absence of oppression is not a “privilege”. In the words of Emma Dabiri, author of What White People Can Do Next: From Allyship to Coalition, “the right to secure housing, or to walk through a shop without being trailed by security, are not privileges. They are rights that belong to every human being”.

Privilege theory fails to talk about the one group of people who are privileged: the ruling class. They’re the ones who hoard all the wealth, decide how production is organised and wield political power in our society. Their privileges are certainly unearned. But privilege theory and allyship insist that it’s working-class people who don’t belong to an oppressed minority group who benefit from oppression, despite the fact that the working class itself is an oppressed class; in fact, it’s the biggest oppressed group in society.

The argument of “privilege theory” is contradicted by the evidence. There are many studies that show that the working class does not materially benefit from oppression and, in reality, suffers from the divisions created by the oppression of specific identity groups within it. For example, in the southern states of the US, where racism is more entrenched due to the legacy of slavery, white workers are paid less than white workers in the north. US economist Michael Reich, after conducting research into this area, concluded that “the greater the divide between black and white incomes the greater inequality within white incomes”. Only the bosses benefit.

Racism and bigotry don’t come just from the ideas in people’s heads, but from the social conditions that are created by those at the top of society that lead some people to adopt distorted views about the oppressed. But according to privilege theorists, those holding strong anti-oppressive ideas must torture themselves until they can confront their inherent bigotry and “decolonise their minds”.

That everyone is a racist deep down is a preposterous premise and merely speaks to the pessimism and passivity at the heart of privilege theory. Either you’re privileged and benefit from the status quo, so don’t want to fight against oppression, or you do want to fight against oppression, but you can’t because that means you’re in denial of your true nature. You’re damned if you do and damned if you don’t!

True to capitalism’s ability to commodify everything, some people are making an absolute fortune hosting workshops designed to tell white workers that they are responsible for the oppression that capitalism itself creates.

Allyship insists that because non-oppressed people won’t give up their social privilege, they should at least give up their material privilege, as reflected in the hashtag #paytherent. Marxists are absolutely in favour of state and federal governments, and national and multinational institutions, paying reparations for the intergenerational destruction of Aboriginal people’s lives. Some activists on the left share this perspective. But increasingly, #paytherent is used, not to mean taking back the wealth from the capitalist class, but to mean that workers who are slightly better paid should give up some of their stuff because they are complicit in the actions of governments and institutions by default because many of them belong to the same identity category as the oppressors.

This broader perspective can take the form of feminists calling for male workers to take wage cuts to close the gender pay gap, or demands for all white people to give money to Black people. Proponents of allyship cheer such developments as successfully securing compensation. But it lets off the hook the bosses and governments who should actually be paying reparations, and it makes fighting oppression a decidedly individual strategy.

The capitalists know that ordinary people’s default is to stand in solidarity with each other. Capitalism could not survive if all the arbitrary divisions that it creates were smashed. That’s why the ruling class has to work so hard to maintain them. Solidarity is the act of actively working against those divisions. Marxists argue that, in the act of fighting to improve their lives through active resistance to oppression, working-class people can overcome the divisions forced on them, whatever their individual identity. Many historical examples suggest this is far from utopian.

For example, in the 1960s, militants on the south coast of NSW used their industrial powers to improve their own working lives and to improve society as a whole. When Aboriginal people were staging sit-ins to be allowed to drink in Wollongong pubs or be served in local shops, workers stood in solidarity with those activists, using their industrial power to hit those businesses economically, setting an impressive pace for desegregation in the area. The solidarity of workers meant desegregation happened in practice well before any legal changes.

In the lead-up to the US Civil War, one in six workers in England worked in the textile industry. There was a widely held view that the South should be supported by workers because that was where the cotton was produced, even if it was by slave labour. But textile workers were won to an understanding of how the abolition of slavery was connected to their own struggles at home for better lives and greater freedom.

This didn’t happen automatically, but through collective debate, not an attempt to “decolonise” individual minds. Karl Marx was at a mass meeting in London and excitedly reported back to his collaborator Friedrich Engels about what he was witnessing from ordinary workers in this regard. This helped inform the important theories that the socialist tradition is built on. He saw in practice the concept of solidarity of the international working class and how a struggle over one issue could breed confidence to struggle over another. The struggle to abolish slavery encouraged the English workers to take up that fight for themselves. A consequence of this act of solidarity was that the leaders of the English working-class movement broadened their own horizons.

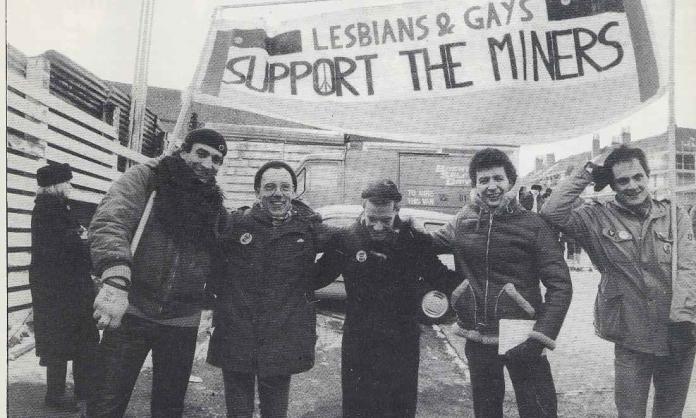

The left-wing activists of Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners recognised that they shared a common enemy with the miners striking in 1984 in Britain: the Tory government led by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. They knew that a victory for the miners would weaken any further Tory attacks on their community. While the year-long strike went down to defeat, the relationships that were built based on solidarity started to change people’s ideas on both sides.

Sections of the LGBTI community were invigorated and politicised by their involvement in the strike, which had an impact when they mobilised against Section 28 (a UK law that prohibited the “promotion of homosexuality”) a few years later. The National Union of Mineworkers called for the Trade Union Council and Labour Party conferences to actively support the gay and lesbian struggle, and demanded that it be taken seriously as a union issue.

The lessons from all of these examples of solidarity are clear: you have to know which side you’re on; fighting gives everyone involved more confidence; the hold of bourgeois ideology can be broken; and people believe that they can win when they can feel their own power.

Oppression will continue as long as capitalism does. But as long as there has been oppression, there has been resistance to it. The idea of working-class solidarity being seen as normal has been somewhat forgotten with the decline of class struggle in the past 30-40 years, but the recent wave of strikes in Britain and France points to what solidarity can look like and how we can win change.

Allyship tells people who want to fight against oppression that their only option is to turn inward and look to individual choices as the solution. But just as it is now widely accepted that keep-cups won’t save the planet from climate destruction, so it must be recognised that individual allyship as a political strategy cannot advance the fight against oppression. Solidarity tells us no-one is free until we are all free, and that our freedom is inextricably linked to the freedom of all the oppressed.