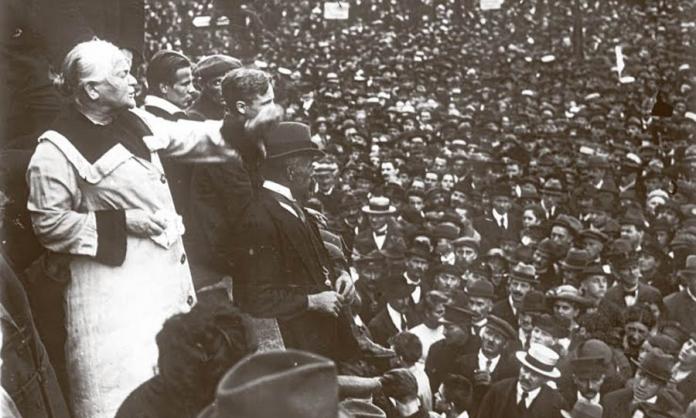

In 1901, the Manchester Guardian reported on the German Social Democratic Party’s (SPD) conference: “Three women especially stand out as really remarkable speakers ... What these ladies do not know in the realm of social politics is not worth knowing. And they support their views not only with cogency and logic, but, when necessary, with a very Niagara of shrill invective.” In spite of the “shrill invective”, the writer admitted: “Whenever one of these female ‘comrades’ occupies the tribune the whole congress pulses with animation”. Clara Zetkin was one of those comrades.

In 1910, at the second International Socialist Women’s Conference in Copenhagen, Zetkin proposed an annual international socialist women’s day be celebrated every March—and so International Women’s Day was established.

But Zetkin should not be remembered for just this one historical act. She is a woman for our times: an inspiration for every woman and man who wants to be part of the struggle for a decent, socialist world.

During the 1880s, living in dire poverty with two children in exile in Paris with Ossip Zetkin (the man whose name she adopted but did not marry), Zetkin was an active union organiser, drawing women workers into the socialist movement.

She became a passionate, articulate orator. Contrary to mythology, this was no “gift from God”. Ossip’s urging and tutoring helped her overcome her original reticence. Able to inspire workers, with whom she identified, she became one of the most popular speakers at their assemblies and in socialist conferences in France and Germany.

She was a ferocious campaigner for universal suffrage, yet forthright in her differentiation from upper- and middle-class women known as “bourgeois feminists”. They just wanted equality with the men of their class and accepted a limited franchise that excluded most workers.

For women workers, the vote was just one step towards full participation in the fight for full emancipation, which was possible only with the overthrow of capitalism. “Bourgeois feminism”, she wrote, “is nothing more than a reform movement, the proletarian women’s movement is revolutionary and must be revolutionary”.

As editor of Die Gleichheit (Equality), the women’s magazine of the SPD, from 1891 to 1917, Zetkin aimed to raise the level of political understanding of women and their participation in the party. She addressed male socialists about the importance of fighting for women’s rights such as equal pay and supporting women’s union activism.

The magazine spread news of union organising, strikes and protests, many of which she was prominently involved in. She campaigned for the right to contraception, including abortion, against the bourgeois feminists’ opposition. A supplement for children promoted ideas missing from their formal education such as the dignity of labour. It explained the economics of capitalism that led to workers’ terrible conditions, alongside articles on science, wildlife and anthropology.

Zetkin stood unwaveringly with the revolutionary left of the SPD, alongside Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht and others, against the party leadership’s increasing emphasis on parliamentary reforms rather than the struggle of workers to overthrow capitalism.

She campaigned tirelessly against the impending war and imperialism. The declaration of war in 1914 opened a chasm in the party. The leadership, opposed by a small minority, backed the government’s call for workers to go and kill other workers. Huge blacked-out columns in Die Gleichheit highlighted her defiant opposition to this complete abandonment of the Marxist internationalism on which the party had been founded and the oppressive censorship laws. Zetkin spent four months in jail in 1915 for her anti-war agitation. In 1917, she was expelled from the SPD.

Zetkin celebrated the victory of the Russian revolution in October 1917. In the turmoil of a workers’ revolution in Germany, she led large numbers of workers into the Communist Party (KPD), formed by Luxemburg and others at the start of 1919.

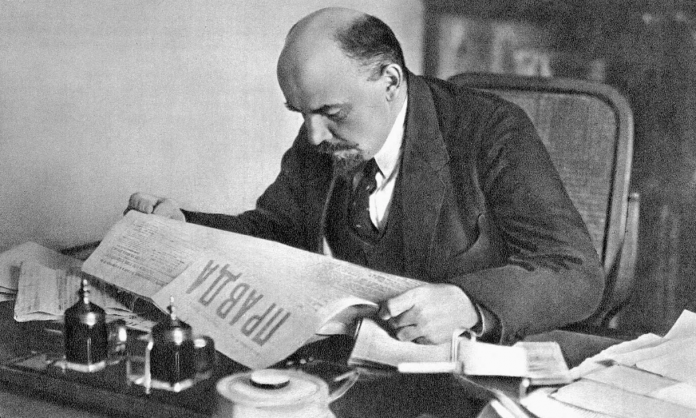

Zetkin was the most prestigious prewar leader still alive in the KPD after Luxemburg, Liebknecht and others were murdered at the instigation of their former SPD comrades. She was elected to leadership bodies at all levels of the KPD as their parliamentary delegate, and in the Communist International set up by Lenin and the Bolsheviks to cohere the international revolutionary movement.

She began to suffer debilitating heart problems and blindness, but this did not stop her actively supporting many campaigns, such as for the rights of Muslim women in the far-flung regions of the Russian Empire. In 1932 she participated in an international campaign to save the Scottsboro Boys from the electric chair—nine black youths, barely 12 years old, convicted by an all-white Alabama jury of a fraudulent charge of rape of two white girls.

In August 1932, just ten months before her death at the age of 75, she made one last courageous stand for all she had lived and struggled for. In the midst of the Nazi terror engulfing Germany, she came out of hiding to take up her right as the oldest MP to open the parliament.

Speaking for over an hour, she passionately articulated her undiminished commitment to the working-class struggle to which she had given her all. She called for “the formation of a United Front of all workers in order to turn back fascism, in order to preserve for the enslaved and exploited the force and power of their organisation as well as to maintain their own physical existence.”

This was a challenge to the KPD leaders, who refused to form such a front, thereby leaving the way open for the Nazi victory. She concluded with the hope that “despite my current infirmities”, she might yet have the fortune to open as honorary president the first congress in a socialist Germany.

We may not all be orators like Clara Zetkin, but we can emulate her determined commitment to the struggle for a world free of exploitation, injustice, war, fascism and oppression.