“One writes out of a need to communicate and to commune with others, to denounce that which gives pain and to share that which gives happiness. One writes against one’s solicitude and against the solitude of others.”

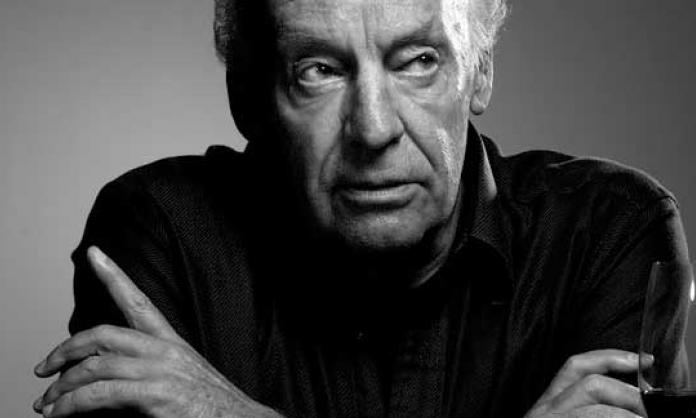

Eduardo Galeano died on 13 April, aged 74. Referred to by many of his peers as one of the greatest Latin American writers, he was a storyteller who chiselled out truth like he was taking revenge. Galeano used language like Brecht did – not as a mirror held up to reality but as a hammer with which to shape it.

His words stretched over the centuries of Latin American history. They were sometimes playful, often pained but always viciously truthful. His countless books, essays and vignettes are a testimony to the fact that the best writing is always partisan.

Galeano was a mouthpiece for the poor, oppressed and exploited. A journalist who got his start in the 1960s with Marcha, an iconic newspaper of the Uruguayan left, he went on to edit and write for many others. He was forced into exile after the 1973 coup and once again had to flee, this time from Argentina, after the 1976 coup. The Uruguayan, Argentinian and Chile dictatorships all banned his first great book, The open veins of Latin America, which he wrote in 1970.

Isabel Allende once said that there was a “mysterious power” in his writing: “He uses his craft to invade the privacy of the reader’s mind”. He was confronting, combining historical knowledge, the wit typical of the southern cone of the Americas and the passion of a continent filled with poets, football geniuses and revolutionaries willing to give their lives for their beliefs.

For these he was an inspiration. Perhaps the best sort of propagandist: able to explain complex ideas simply but in all their connections, weaving history with hope. If I could recommend a t-shirt be made in his honour, it would read: “‘The system vomits people’, Eduardo Galeano”.

His didactic prose was reminiscent of Roque Dalton or Mario Benedetti – the latter at one point also was a journalist with Marcha. But perhaps more than most, Galeano seemed capable of depicting the beauty that survives among the rot. When Albert Camus wrote “every act of rebellion expresses a nostalgia for innocence”, he anticipated Galeano, who always sought to “reveal the hidden greatness of the small, of the little, of the unknown – and the pettiness of the big”.

He told the stories that are told in kitchens and backyards, not those made up in boardrooms and editorials. He once said: “Scientists say that human beings are made of atoms, but a little bird told me that we are also made of stories”.

Galeano was the champion of la memoria viva: the re-telling and celebration of working class memory. “The good story-teller tells their story and makes it happen”, he said.

If we take anything from his life it should be to keep telling the story he did not get time to make happen: the story of revolution.