Craig Kelly—leader of the right-wing United Australia Party (UAP) and a prominent figure in the so-called “freedom movement” against COVID-19 related public health measures—recently claimed the movement’s protest in Melbourne on 20 November was “possibly the largest ever political rally in Australia”. The UAP’s billionaire founder Clive Palmer put the attendance at 500,000.

Leaders of protests movements, whether left or right-wing, have an obvious interest in inflating the numbers at their events. But in this case, it seems, the inflation was greater than usual. Most estimates of the attendance at the 20 November rally in Melbourne—by media outlets as well as Victoria Police—range from 10,000 to 20,000. Even assuming that this could significantly underestimate the real total, it’s unlikely the turnout was over 50,000.

The Melbourne rally on 20 November was the biggest of all the freedom movement protests that have occurred in Australia to date. So while it’s alarming that a motley crew of right-wing politicians like Kelly, far-right and neo-Nazi individuals and organisations, and anti-vaxxers have over the past few months consistently mobilised large numbers on the streets, these are far from the biggest rallies in Australia’s history.

Even if only the past few decades are considered, many left-wing protests were significantly bigger. Here are five of the clearest examples.

The 2019 climate strikes

In 2019 millions of high school students and other climate activists all around the world followed Greta Thunberg’s call to strike for immediate action on the climate crisis and an end to the fossil fuel industry. The high-point of this movement to date occurred in September 2019, when an estimated 300,000 people marched in cities and towns across Australia, with 100,000 gathering in Melbourne alone.

The 2005 union rallies against WorkChoices

In November 2005, an estimated 175,000 people marched in Melbourne against the Howard government’s union-busting WorkChoices legislation, which would have undermined collective bargaining and allowed bosses to put workers on conditions below previously established legal minimums.

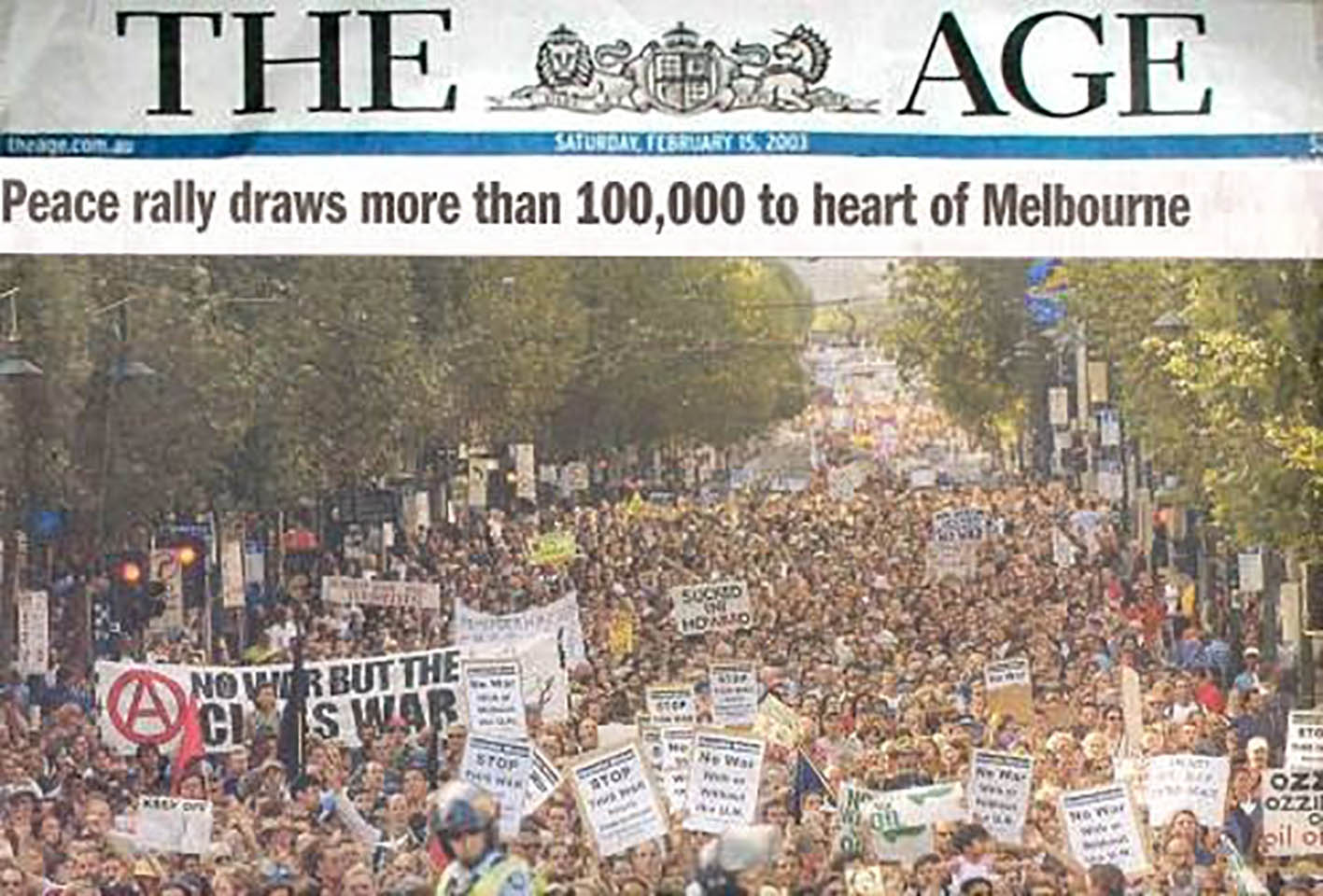

The 2003 protests against the Invasion of Iraq

On 15-16 February 2003, international demonstrations against the US push for war with Iraq brought out an estimated six to ten million people—among the biggest global protests in history. In Sydney, the crowd was over 200,000, while 150,000 marched in Melbourne.

The 2000 reconciliation marches

In May 2000, an estimated 250,000 marched for reconciliation across the Sydney Harbour Bridge in Sydney. The Melbourne and Perth rallies were also estimated at between 200,000 and 300,000. More recently, the 26 January Invasion Day protests have also likely been larger than the right’s “freedom” protests—with tens of thousands of people marching in Melbourne and elsewhere every year.

The 1992 rallies against Jeff Kennett

Given the dominant political currents within the freedom movement, it’s likely many participants would have celebrated the savage neoliberal attacks launched by Victorian Liberal Premier Jeff Kennett following his election in 1992. But in November that year, 100,000 Victorians rallied against Kennett’s attacks on the working class, which included anti-union laws, cuts to penalty rates, and privatisation of public services.

It’s unsurprising, on one level, that the current “freedom” rallies would be significantly smaller than these left-wing protests. In contrast to public sentiment around the demand, for example, for action on climate change (a big majority of Australians want much more serious action than the government has been prepared to take), the views expressed by those in the freedom movement represent a very small fringe of Australian society.

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the measures implemented by Victorian Labor Premier Daniel Andrews to limit the burden of death and disease inflicted on society, while clearly not perfect, have been supported by a big majority of the public. This includes even the most contentious measures, such as workplace vaccine mandates, which a recent Roy Morgan poll found are supported by 76 percent of people.

This however, understates the danger that these right-wing mobilisations represent. While they may be small relative to big left-wing protests of recent decades, their enduring nature, and the platform they’ve provided for the far-right and neo-Nazis to spread their influence and recruit, is cause for serious concern. The aim of movement figureheads like Clive Palmer is, more or less explicitly, to import a Trumpian brand of mass right-wing politics to Australia. This, and the growth of the violent far-right groups that swim in those waters, must be strongly opposed by the left.

That’s why groups like the Campaign Against Racism and Fascism in Melbourne, and other activists around the country (including Brisbane, Sydney, Canberra, Adelaide and Perth), have begun to mobilise in opposition to right. If only a fraction of the people who joined rallies like the 2019 climate strike also joined these counter-protests supporting vaccination and other public health measures to protect workers from death and illness from COVID-19, and opposing the far right and the “profits over life” agenda of Clive Palmer and other freedom movement leaders, we could start to push them back.