Sydney is one of the most unaffordable places in the world to buy or rent a house, coming in second behind Hong Kong. There is also a severe lack of public housing, the NSW government selling much needed houses for the poor and disadvantaged while the waiting list has blown out to more than 57,000 people.

But 50 years ago, there was an insurgent workers’ movement in the city that fought the government and property developers who tried to tear down working-class houses and public housing developments in the pursuit of profits. It was led by the militant NSW branch of the Builders Labourers Federation (BLF).

Builders' labourers performed the hardest and most dangerous jobs on worksites, such as digging trenches, pouring concrete and riding crane hooks with steel and other materials to the top of buildings. Without them, building sites ground to a standstill. Using their power, the BLF pioneered “green bans” to save parklands, historic buildings and working-class housing.

The most famous green ban occurred in the Rocks, where BLF members refused to tear down public housing.

The Rocks Resident Action Group had been campaigning to save their community from the greedy fingers of the NSW Liberal government, which, from 1970, showed a keen interest in turning the area into an extension of the CBD, with glitzy hotels, office blocks and shopping centres. The leader of the action group, Nita McRae, was a fifth-generation resident and had contacted around 30 unions. The union that responded first was the BLF.

And respond they did. From November 1971 to May 1975, the BLF instituted a green ban to stop public housing being torn down until all 416 residents were happy with the government’s plan. Builders' labourers stopped work on all sites for the four years of the ban.

The government had spent years neglecting maintenance on the public housing and had raised rents between 200 and 300 percent in an attempt to get residents to move out. In response to these tactics, BLF officials Bob Pringle and Joe Owens said: “Progress should be for all the people and not be detrimental to some for the benefit of others”.

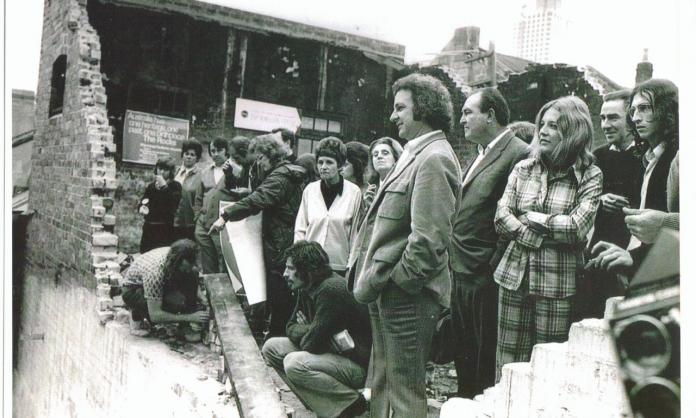

The ban reached a high point in October 1973, when Premier Robert Askin decided to make the Rocks the site of a law-and-order campaign to support his upcoming re-election campaign. Residents and builders' labourers barricaded a demolition site on Playfair Street and climbed onto the roofs and even into surrounding trees. Askin sent in the police, and their response was brutal, arresting large numbers of residents and BLF members, including union Secretary Jack Mundey.

During the life of the green ban, more than 70 buildings were restored by workers. Cheap restaurants, art galleries and craft centres were established, breathing new life into the community. Eventually, the government dropped plans to redevelop the Rocks.

The BLF also helped the Aboriginal community in Redfern establish their own housing block, run by the community.

In 1972, a developer who had bought up a block of houses in which Aboriginal families had lived for decades laid out plans to knock them down and turn them into expensive town houses. Activists reached out to the BLF. Rather than allow the Aboriginal families to be evicted and the houses torn down, union members put a green ban on the site until March 1973.

As a result, Gough Whitlam’s ALP federal government bought the houses and turned them over to the community, who set up much needed low-cost housing for Aboriginal people.

Sixty-five homes were saved, a communal meeting space was established, two nearby factories were turned into a preschool, medical centre, multipurpose hall, workshop, gym and cultural centre, and a co-operative was set up nearby to sell groceries cheaply.

The working-class community of Victoria Street in Kings Cross—inhabited by wharfies, seamen, labourers, city workers and artists—was also under threat. Developer Frank Theeman wanted to tear down terrace houses to put up three large office towers in 1973.

At the request of the 300 residents of Victoria Street, the BLF implemented a green ban. Residents were terrorised by thugs hired by Theeman, threatened with evictions and had their utilities disconnected, and some were forcibly evicted. Locks were removed, doors were kicked in, and bricks and rocks were thrown through windows at night.

The leader of the residents’ action group, Arthur King, was even abducted for several days. After many residents left their homes due to the intimidation, squatters organised to live in the empty dwellings to look after them and prevent arson and vandalism.

While demolition work was halted, the National Trust deemed that Victoria Street had significant historical and architectural merit and ought to be preserved. In January 1974, Theeman was forced to revise his plans significantly to maintain the character of the street, which included scrapping the large office towers, keeping the terrace houses and building several low-cost houses.

The home-grown green bans had become a world-leading example of working-class power. What drove BLF members to take up the defence of working-class communities with such militancy?

The green bans occurred at the same time as a broader radicalisation was happening in society. The BLs had been inspired by the anti-Vietnam War campaign led by students and the anti-apartheid solidarity campaign with Black people in South Africa. The BLF was also one of the first unions to support Aboriginal land rights.

The BLF at this time was also largely influenced by the working-class politics of the Communist Party. Communists spent many years organising the union’s rank and file, who gained confidence from battles they had won for better pay and safe working conditions. And the union’s officials believed that workers ought to have a say over what was built in Sydney, Mundey declaring:

“Yes, we want to build. However, we prefer to build urgently required hospitals, schools, other public utilities, high-quality flats, units and houses, provided they are designed with adequate concern for the environment.”

The BLF was eventually smashed by the government and rival unions, but its legacy lives on: not just in Sydney’s built environment and all the buildings and parklands saved by the BLs and their green bans, but in the traditions of the organised working class, when workers continue to stand up collectively against a system that tries to strip us of our power and our humanity.