The second half of the 1970s was calamitous for US imperialism. The last American troops withdrew from South Vietnam in 1975 as Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City) fell to communist forces from the North. Iran’s US-friendly regime collapsed in February 1979 after a revolution toppled Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, whom the Americans had previously installed in a coup.

In the Caribbean island nation of Grenada the following month, communists in the New Jewel Movement took power, rekindling memories of the Cuban revolution. And the US-backed dictatorship in Nicaragua, Central America, was also about to fall to left-wing guerrilla forces. The Americans seemed to be losing everywhere.

For President Jimmy Carter and the US national security establishment, the Iranian setback in particular could not have come at a worse time. Communists—backed by the United States’ key strategic enemy, the Soviet Union—recently had taken power in neighbouring Afghanistan. While the country wasn’t high on the list of US priorities, US strategists nevertheless sensed an opportunity in the otherwise miserable situation. In July, under advice from National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski, Carter signed a directive allowing secret aid to be given to what was by this time a radicalising opposition to the pro-Soviet government.

It marked the beginning of a now infamous convergence of interests, through which the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), the Saudi Arabian General Intelligence Department (GID) and Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence Directorate (ISI) trained and equipped the Afghan mujahideen (Islamic guerrillas) resistance. Each member of this alliance had its own agenda.

“President Zia aimed to cement Islamic unity, turn Pakistan into the leader of the Muslim world and foster an Islamic opposition in Central Asia”, Ahmed Rashid wrote at the US Center for Public Integrity in 2001. “Washington wanted to demonstrate that the entire Muslim world was fighting the Soviet Union alongside the Afghans and their American benefactors. And the Saudis saw an opportunity both to promote Wahhabism [a puritanical strain of Islam] and to get rid of its disgruntled radicals. None of the players reckoned on these volunteers having their own agendas, which would eventually turn their hatred against the Soviets on their own regimes and the Americans.”

Russian troops invaded the country in December, fearing the imminent overthrow of the government by the mujahideen and concerned about a potential chain of rebellion throughout its own, predominantly Muslim, Central Asian republics. The Soviets were now caught in an intractable war. Over the next decade, the CIA, the GID and the ISI recruited more than 30,000 fighters from the Muslim world and channelled billions of dollars in aid to train and equip them.

The Washington Post’s Steve Coll called it the most significant covert operation since the Second World War. “At any one time during the Afghan fighting season, as many as eleven ISI teams trained and supplied by the CIA accompanied mujahideen across the border to supervise attacks”, he wrote in 1992.

They gave support to retrograde characters such as Gulbuddin Hekmatyar. His followers, according to journalist Tim Weiner, were known to throw acid “in the faces of women who refused to wear the veil”. “CIA and State Department officials I have spoken with call him ‘scary’, ‘vicious’, ‘a fascist’, ‘definite dictatorship material’”, Weiner writes in Blank Check: The Pentagon’s Black Budget.

Hekmatyar, who in 1976 founded Hezb-e-Islami (Party of Islam), a paramilitary political organisation, reportedly received more American funding than any other warlord. (Ironically, he was later placed on Washington’s most wanted terrorist list.) The reasoning of the CIA was simple: the more fanatical the soldiers and the more brutal their methods, the more they would hurt the Russians. And the more pain they inflicted, the more support they should receive.

Ronald Reagan, who took over from Carter in 1981, described the mujahideen as “freedom fighters” and brought to Washington rebel leaders such as Abdul Haq, who admitted his responsibility for terrorist attacks such as a 1984 bomb blast at Kabul’s airport that killed at least 28 people and wounded hundreds of others. His US admirers nicknamed him “Hollywood Haq”.

Using the personnel and vehicles provided by the CIA, the mujahideen expanded opium production in areas under their control, turning Afghanistan into what one US Drug Enforcement Administration official later described as the new Colombia of the drug world. (These were also the years that the CIA provided covert funding, raised through the sale of cocaine, to anti-government paramilitaries in Nicaragua.) US support wasn’t forthcoming only for military operations. The ideological war was also assisted, as Rashid noted:

“Tens of thousands more foreign Muslim radicals came to study in the hundreds of new madrassas that Zia’s military government began to fund in Pakistan and along the Afghan border. Eventually more than 100,000 Muslim radicals were to have direct contact with Pakistan and Afghanistan and be influenced by the jihad.

“In camps near Peshawar [near the Afghanistan border] and in Afghanistan, these radicals met each other for the first time and studied, trained and fought together. It was the first opportunity for most of them to learn about Islamic movements in other countries, and they forged tactical and ideological links that would serve them well in the future. The camps became virtual universities for future Islamic radicalism. None of the intelligence agencies involved wanted to consider the consequences of bringing together thousands of Islamic radicals from all over the world.”

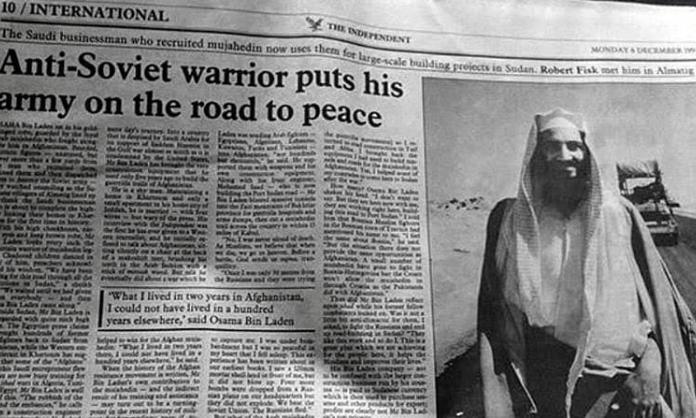

Osama bin Laden, the seventeenth son of a Saudi construction billionaire, became involved early in the conflict as a recruiter and financier. “Delighted by his impeccable credentials, the CIA gave Osama free rein in Afghanistan, as did Pakistan’s intelligence generals”, journalist John Cooley writes in Unholy Wars: Afghanistan, America and International Terrorism. “They looked with a benign eye on a build-up of Sunni Muslim sectarian power in South Asia to counter the influence of Iranian Shi’ism of the Khomeini variety.”

Bin Laden recruited thousands of volunteers from Saudi Arabia and developed close relationships with mujahideen leaders. He also reportedly worked closely with the CIA, raising money from private Saudi citizens. From 1984, bin Laden, along with Ayman al-Zawahiri and others, ran the Maktab al-Khidamat, which was set up by the ISI to provide resources to the mujahideen. Also known as the Afghan Service Bureau, the organisation was the forerunner of al-Qaeda (founded in 1988), the terrorist network responsible for the 11 September 2001 attacks on the United States.

“Operating from Karachi at first and later from his strongholds in Afghanistan, bin Laden’s financial and construction empire set about building the bases and training camps and landing strips in Afghanistan—under attack in the winter of 2001-02 by the United States, which had originally encouraged their building—for private jets of warlords of the anti-Soviet jihad, and for visiting Muslim and Arab dignitaries”, Cooley writes.

“Deeply buried bunkers and tunnels for command posts and telecommunications centers ... were carved out of the Afghan mountains. They were meant to make telecommunications of the mujahideen fighters proof against the radio traffic analysts and codebreakers of the Red Army, as well as to secure the munitions, weapons and fuel stores against attack by Soviet land and air forces.

“Long before the war ended, bin Laden and his acolytes were preparing for the larger jihads to come against the impious Arab governments which, he felt, were beholden to the corrupt and satanic United States, with which, as an objective ally, he had been working to expel the Soviets.”

By 1989 the Russians were exhausted. Afghanistan had become to them what Vietnam had been to the US. When they finally withdrew, the administration of George H.W. Bush turned its back on Afghanistan, leaving it, in the words of the Economist, “awash with weapons, warlords and extreme religious zealotry”.

Bin Laden also left the country and began to reorient al-Qaeda. But he was forced to return in 1996, having been stripped of Saudi citizenship and expelled from Sudan because the US had finally turned on him. “He brought with him scores of hardened Arab radicals fired by visions of global Islamic war”, Steve Coll writes in Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan, and Bin Laden. From the Hindu Kush, bin Laden called for war, wroting a poem to US Secretary of Defense William Perry:

O William, tomorrow you will be informed

As to which young man will face your swaggering brother

A youngster enters the midst of battle smiling, and

Retreats with his spearhead stained with blood.

Looking back on his role in the Afghan conflict, Zbigniew Brzezinski asked in 1998: “What is most important to the history of the world ... some stirred up Muslims or the liberation of central Europe and the end of the Cold War?” Read in the light of what came next, the question is tragic.