In jail for her anti-war stance in 1916, Rosa Luxemburg, the great Polish-German revolutionary, wrote what became known as The Junius Pamphlet:

“Violated, dishonoured, wading in blood, dripping filth—there stands bourgeois society. This is it [in reality]. Not all spic and span and moral, with pretence to culture, philosophy, ethics, order, peace, and the rule of law—but the ravening beast, the witches’ sabbath of anarchy, a plague to culture and humanity. Thus it reveals itself in its true, its naked form ...

“We stand today ... before the awful proposition: either the triumph of imperialism and the destruction of all culture ... depopulation, desolation, degeneration, a vast cemetery; or, the victory of socialism.”

The hellish war she describes ended with a wave of revolutions that threatened to bring down capitalism.

But in the early days of the war, the socialist parties of Europe mostly capitulated to the chauvinism of their rulers.

“In the midst of this witches’ sabbath a catastrophe of world-historical proportions has happened: International Social Democracy has capitulated”, wrote Luxemburg.

The syndicalist Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in Australia were one of the few organisations that immediately opposed the war. On 10 August 1914, the front page of their paper Direct Action was emblazoned with the statement:

“WAR! WHAT FOR? THE WORKERS AND THEIR DEPENDENTS: DEATH, STARVATION, POVERTY AND UNTOLD MISERY. FOR THE CAPITALIST CLASS: GOLD, STAINED WITH THE BLOOD OF MILLIONS, RIOTOUS LUXURY, BANQUETS AND JUBILATION OVER THE GRAVES OF THEIR DUPES AND SLAVES. WAR IS HELL! SEND THE CAPITALISTS TO HELL AND WARS ARE IMPOSSIBLE.”

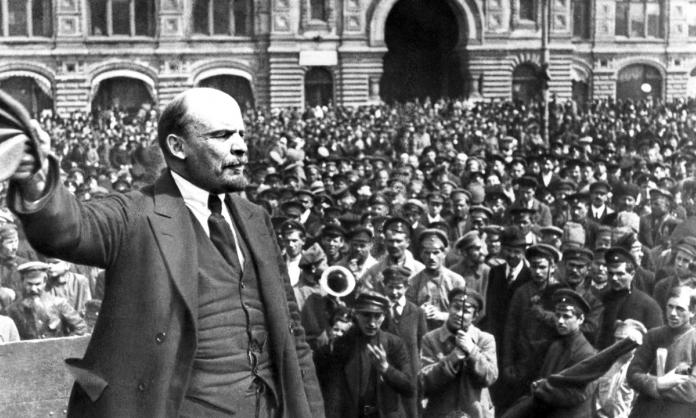

The Russian Bolshevik party, led by Vladimir Lenin, was one of only a tiny number of mass socialist parties that stood firm against their government in the war. Despite a police crackdown, they issued 70 leaflets in St Petersburg in the first four months, agitating against support for the war. They refused to refer to St Petersburg as Petrograd, in defiance of the chauvinism that inspired the name change.

Lenin argued that the task for Marxists was first to stand against the tide of patriotic fervour in every country, even if it made them unpopular for a while. Within weeks he summed up his approach in an article titled “War and Revolution”, arguing that “the best war on war is revolution”.

Lenin’s strength was that he never gave in to despair. He had always argued that capitalism would inevitably suffer crises that would give rise to revolutionary opportunities. Now that prospect was real.

Moderates like the Russian Mensheviks simply raised the slogan of “peace” in the expectation that the masses would, in time, want peace. Lenin agreed that would be the case, but predicted that arguing for a “peace strategy” could not lay the basis for revolutionary leadership of that sentiment when it developed.

He wrote: “The age of bayonets is upon us. This is a fact, and in consequence we must fight with similar weapons”. For Lenin, the most powerful weapon was mass action against the bourgeoisie’s war: “Our slogan is civil war to stop the imperialist war”.

Others argued Lenin’s call for “civil war” was unrealistic because, when workers tired of the war, they would want peace, not slogans about more war. Lenin replied: this is “pure sophism”. We cannot “make” civil war immediately, “but we propagate for it and work in this direction. In every country one must struggle first of all against one’s own proper chauvinism, awaken hatred for one’s own regime, call (repeatedly, persistently, ever again, tirelessly) for solidarity among the workers of the warring nations.

“No one is proposing to guarantee when and to what degree this work will prove practicable or justified: This is not what is at issue ... Only such work is socialist and not chauvinist. And it alone will bear socialist fruit, revolutionary fruit.”

And he was proven right. On International Women’s Day in Petrograd in February 1917, tens of thousands of women workers left the factories on strike. The powerful metal workers responded to their calls and joined them.

The tsarina, wife of Tsar Nicholas II, dismissed their protest as “a hooligan movement”, informing Nicholas that “if the weather was cold, they would probably stay at home”. Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky described the circles she lived in:

“Speculation of all kinds and gambling on the market went to the point of paroxysm. Enormous fortunes arose out of the bloody foam. The lack of bread and fuel in the capital did not prevent the court jeweller Fabergé from boasting that he had never before done such a flourishing business.

“‘Society’ held out its hands and pockets, aristocratic ladies spread their skirts high, everybody splashed about in the bloody mud—bankers, heads of the commissariat, industrialists, ballerinas of the tsar and the grand dukes, orthodox prelates, ladies-in-waiting, liberal deputies, generals of the front and rear, radical lawyers ...

“All came running to grab and gobble, in fear lest the blessed rain should stop. And all rejected with indignation the shameful idea of a premature peace.”

How could the tsarina understand the depth of anger and bitterness among the workers, soldiers and peasants? It was the police spies, who mingled among the increasingly restless workers, who recorded the misery and sacrifice she did not see.

In January, a police report had noted that Russia’s working class was “on the edge of despair ... the slightest explosion, however trivial its pretext, will lead to uncontrollable riots ... The inability to buy goods ... the rising death rate owing to poor living conditions, and the cold and damp produced by lack of coal ... have all created [this] situation”.

Report after report recorded the atmosphere of tension and class conflict as strikes grew in the city.

“[M]others of families, exhausted from the endless queues at the shops, suffering at the sight of their sick and half-famished children, at this moment ... constitute a mass of inflammable matter for which only a spark is sufficient to cause it to burst into flames”, wrote a police spy during the February revolution.

All this against the backdrop of hundreds of thousands wounded and dead.

The officers were no match for courageous Bolshevik women such as Zhenia Egorova. Their appeals to the war-weary soldiers to “Put down your bayonets—join us!” struck at the soldiers’ hearts. They disobeyed their officers and joined the protesters.

Five days after the strikes began, the 300-year-old Romanov autocracy had been trampled under the feet of these “hooligans”, who were supported by virtually the entire workforce of Petrograd and Moscow, and strengthened by the soldiers’ mutiny.

The rebellion spread like wildfire to other urban centres, across the fertile plains, the frozen tundra and the mountainous Caucasus of the Russian empire. The tsar was forced by his own generals to abdicate in a stranded railway car 300 kilometres south of Petrograd because workers refused to move his train.

Millions, driven by the barbarity of war and the luxuries of the wealthy, were shaking their centuries-old chains of oppression.

Yes, they wanted peace, but it was clear they had to fight their own ruling class to get it. Lenin’s slogan, “Turn the imperialist war into civil war”, had prepared the Bolsheviks for just such a fight. It became increasingly clear during 1917 that Russia’s rulers preferred a German military dictatorship to the revolution.

In October, the Bolsheviks led the second revolution, establishing a government based on workers’ power. Their first decree declared the determination to end the war.

News of the October Revolution inspired revolts far beyond Russia’s borders. Thousands of soldiers were deserting their armies; nearly half of the French army was affected by mutiny.

In November 1918, a mutiny of German sailors quickly grew into a workers’ revolution. Faced with the prospect of being overthrown, the German state sued for peace.

The subversion of armies across Europe and the revolutionary actions of workers had brought the imperialists to their knees.

In country after country—Finland, Hungary, France, Italy—workers rose in their millions. In some countries, mass strikes terrified the ruling class; in others, revolutions brought down governments.

In Australia, strikes and militant mass protests defeated referendums to introduce conscription in 1916 and 1917. Thousands of women workers protested night after night in the streets of Melbourne in September 1917, leaving a trail of smashed plate glass windows as they marched.

The rebellions continued around the world until 1923.

But, tragically, in every case workers were defeated. Some, like the IWW, were crushed by repression for which they were ill prepared. The German Social Democratic Party, along with all the parliamentary reformists of Europe, sided with the capitalists and helped save the system from the wrath of workers and soldiers.

Despite these defeats, there are fundamental lessons to learn from these years.

At times workers, ground down by defeats and setbacks, or when they have won some reforms, might be quiescent. But capitalism regularly descends into economic or social crises, pushing workers to respond with explosions of militancy and radicalism.

These times of turmoil propel masses of people into struggle, though often with little experience. Victory is not inevitable in the face of ruling-class violence and political attacks.

A fundamental problem in World War I and its aftermath, which held so much promise, was that no other revolutionary parties like the Bolsheviks had been built ahead of time.

An organisation clearly committed to revolution can be the decisive factor. It needs an experienced membership that can translate the theories of Marxism into the language of struggle to convince workers to take power into their own hands.

The mass socialist parties that emphasised parliament as the way to change society turned against workers and defended the capitalist state.

Rosa Luxemburg was one of the determined revolutionaries who stood against war and repression without flinching. But she had no clear revolutionary group cohered around her.

When the mass revolt engulfed Germany in November 1918, she paid with her life. She was murdered, along with her close comrade Karl Liebknecht, by soldiers at the instigation of their former SPD comrades.

The last words she wrote in January 1919, as she saw the revolution unravelling all around, expressed her unshakeable confidence that workers would one day end the barbarism of capitalism:

“The revolutionary struggle is the very antithesis of the parliamentary struggle. In Germany, for four decades we had nothing but parliamentary ‘victories’ ... And when faced with the great historical test of August 4, 1914, the result was the devastating political and moral defeat, an outrageous debacle and rot without parallel.”

There has been too much suffering and blood spilled in defeated workers’ struggles. We are entering a new period of militarism and the threat of war, to say nothing of the economic and environmental catastrophes that will destroy the lives of billions. We must learn the lessons of the past, lest the sacrifices be endlessly repeated.