Across Indonesia, vast swathes of forest and peat land are burning, destroying the habitats of countless endangered species, poisoning the air and threatening the health of tens of millions of people.

The fires have been called the greatest environmental disaster of the 21st century.

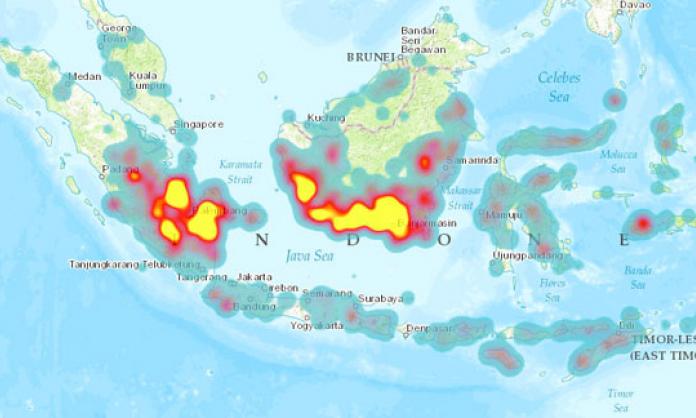

By the end of October, more than 127,000 blazes had been detected, the main hotspots being on the islands of Sumatra and Kalimantan. Smoke has blanketed not only Indonesia, but Singapore, Malaysia and parts of the Philippines and Thailand.

The peat fires are responsible for a particularly dangerous cocktail of emissions. Peat is composed of partly decomposed plant material that builds up in wetland areas over thousands of years. When burnt, it releases much higher levels of carbon dioxide, methane and other toxic gases than do ordinary forest fires.

The current outbreak began in August. Over the subsequent two months, at least 19 people died and more than 500,000 sought medical help for respiratory illnesses.

The last time Indonesia suffered a fire crisis of this magnitude was in 1997. George Monbiot, writing in the Guardian, noted:

“After the last great conflagration … there was a missing cohort in Indonesia of 15,000 children under the age of three, attributed to air pollution. This, it seems, is worse. The surgical masks being distributed across the nation will do almost nothing to protect those living in a sunless smog. Members of parliament in Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo) have had to wear face masks during debates. The chamber is so foggy that they must have difficulty recognising one another.”

In Singapore, note journalists Malcolm Farr and Charis Chang, people “have been keeping their children inside as much as possible for the past two months.

“They have abandoned outdoor fitness routines such as jogging and have become used to never seeing the sun through the immovable haze, which is so thick, cars parked on the street can’t be ... seen by residents in high-rise towers above.”

In the long term, the impact will be felt globally. According to the World Resources Institute, for most of the last two months the daily emission of greenhouse gases from the fires has exceeded that of the entire US economy. The fires are, in part, a product of a rapidly warming world, and they will, in turn, contribute to further warming in decades to come.

The majority are deliberately lit as a cheap and easy way to clear the land for pulp wood and palm oil plantations. The carbon-rich peat land is highly sought after. Canals are constructed to drain the wetlands and allow the peat to dry out and burn.

The plantations are big business. Palm oil is an ingredient in up to 50 percent of packaged items commonly found in supermarkets and makes up 65 percent of vegetable oil on the global market. Indonesia is the world’s largest palm oil producer. In 2014, it was the country’s third biggest export, worth US$18.9 billion.

In the name of “development”, governments in countries such as Indonesia have encouraged a shift away from more traditional local economies and created conditions in which monocultures producing for the global market become the only option for communities struggling to survive.

These desperate people in many cases light the fires, and they are the ones who will bear the brunt of the Indonesian government’s efforts to appear to be taking a tough approach to the issue. But the root of the problem lies elsewhere.

Local farmers are linked to vast global supply chains dominated by giant corporations – companies like McDonalds, PepsiCo, Subway and Costco – whose windfall profits depend on their ability to source ingredients at the lowest possible price. The connections may be hard to trace. But the flow of profit tells the story.

The local farmers might secure enough to lift themselves out of abject poverty. But those higher up the chain reap the lion’s share of the benefits. Significantly, this includes local and national government officials whose political careers often depend on their connections to the big-money interests that profit most from the continued expansion of the plantations.

The Indonesian inferno is a glimpse into a future of unbridled capitalism and runaway warming. It’s not a pretty sight.