In Sydney’s largest ever protest, hundreds of thousands of workers took to the streets in May 1932 to denounce the coup by the state governor, Sir Philip Game, that overthrew Jack Lang’s Labor government.

It was not just in Sydney. Rural Bathurst, where thousands of workers demonstrated and railway workers talked of revolution, was typical of working-class centres all over NSW. Even in tiny Koorawatha, where my teenage father grew up, his uncle armed himself with a revolver to prepare to fight in what he saw as the coming civil war.

The coup was the end product of a furious ruling-class mobilisation to bring down Lang, who was portrayed as the devil incarnate, desecrating noble British traditions and the rights of property by reneging on interest payments to London bankers. As the Sydney Morning Herald declaimed: “No communist howling for the overthrow of social order in this state has ever said things worse than Lang”.

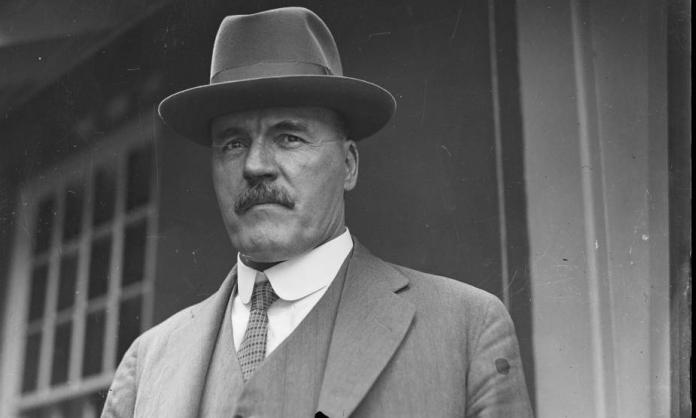

The fascist New Guard armed and drilled tens of thousands of “respectable” middle-class citizens in an attempt to depose Lang. Even more threatening was the military might of the highly secretive Old Guard, headed and funded by a virtual who’s who of the banking, business and military establishment, which was waiting in the wings ready to take over if the governor did not uphold his “duty” to King and country and depose Lang.

On the other side of the class divide, workers proclaimed “Lang is right”. Faced with the mass unemployment and misery of the Great Depression and following the abject capitulation of the Scullin federal Labor government to employers’ demands for harsh austerity measures, masses of workers viewed Lang as the only Labor leader prepared to stand up for them.

The mantlepieces of working-class homes all across NSW proudly displayed busts of the “Big Man”—Jack Lang, hailed by Jock Garden, Sydney’s top trade union leader and former head of the Communist Party, as “greater than Lenin”.

But Lang was no Lenin. Like Gough Whitlam in almost identical circumstances four decades later, Lang made no call on his working-class supporters to mobilise to fight the coup.

Lang meekly walked away, allowing the bosses to get away with their brutal assault on basic democratic rights. The workers who had looked to him for hope in the midst of the horrors of the Depression were left utterly demoralised and at the mercy of a capitalist class determined to ensure that workers bore the burden of capitalism’s worst economic crisis.

Lang, a real estate agent from suburban Auburn, was always an unlikely working-class hero. First elected in 1913, he was very much part of the moderate Labor mainstream in his initial decade or so in parliament—a strident advocate for class collaboration, arbitration and “White Australia”, and a virulent anti-communist.

As treasurer in the Labor government of the early 1920s, Lang was thoroughly committed to capitalist economic orthodoxy. However, in the mid-twenties, in the context of the no-holds-barred factional warfare that engulfed NSW Labor in these years, Lang, for entirely opportunist reasons, made a leftward shift.

To gain the party leadership and maintain it in the face of entrenched opposition from numerous state MPs and the conservative Australian Workers Union (AWU, then NSW’s largest union), Lang needed the support of left-wing and moderate unions. By 1926, Lang had formed a pact with Jock Garden, head of the “Trades Hall Reds” who controlled the NSW Labor Council.

Garden, a consummate wheeler and dealer, had recently abandoned the Communist Party. He and the coterie of left union officials around him were now looking to stamp themselves as major players in the ALP. After a brief flirtation with the AWU, Garden threw himself in with Lang. Garden was one of the key players in getting the numbers at a special Labor conference in November 1926, which removed the right of the parliamentary caucus to elect the party leader and confirmed Lang as premier for the life of that parliament.

In order to keep his union backers on side, Lang, in his first year as premier, initiated a mildly reforming agenda: restoring the 44-hour week abolished by the previous conservative government, improving workers’ compensation, increasing widows’ pensions and returning seniority to rail workers victimised after the 1917 mass strike. However, in 1927 Lang capitulated to concerted ruling-class pressure and the reforms stalled sharply.

Nonetheless, Lang’s reputation as a radical reformer and a strong “fighter for the people” had been established. He had become the bogey man of the right-wing press.

Unemployment was sharply on the rise in Australia well before the October 1929 Wall Street crash, and the bosses were on the offensive to drive down wages and working conditions. In a series of key industries—the waterfront, the coal mines and the timber industry—the employers, with the full backing of the arbitration courts and governments, went for the jugular.

Bitter and prolonged strikes by waterside workers and timber workers (out for eight and a half months) were crushed. Workers protesting against scabs at Port Melbourne were shot and killed by the Hogan Labor government’s police.

The most prolonged battle was on the coalfields around Newcastle, where workers were locked out for sixteen months, and even then only reluctantly returned to work following the total surrender of their union officials.

With class tensions heightening, federal Labor was swept to office with a record majority in October 1929. Labor leader James Scullin had pledged to create jobs, defend working-class living standards and end the lockout of the coal miners.

But Labor’s pledges were soon abandoned. Totally unprepared to stand up to the bosses, the Scullin government imposed austerity measures on workers and pensioners to help prop up profits, did not lift a finger to end the lockout and completely failed to stem the relentless rise in unemployment, which reached 21 percent in mid-1930 and peaked at 32 percent in 1932.

In the October 1930 NSW elections, Lang ran on a platform critical of the austerity measures of the conservative NSW government and the lack of action by federal Labor. He called on Scullin to send in troops to seize the coal mines from the bosses.

Lang triumphed with 55 percent of the vote and 55 of the 70 seats in the Legislative Assembly. He moved to restore the 44-hour week and ensured that the state Industrial Commission did not impose the 10 percent wage cut decreed by the federal Arbitration Court.

In June 1931, the Scullin government endorsed the Premiers Plan that imposed even more misery on workers and the poor with a 20 percent cut to government spending—slashing public works, welfare entitlements and public service salaries. Lang had put forward his own plan that called for lower interest rates and the suspension of interest payments on government overseas debts.

The Lang Plan was in no sense anti-capitalist, let alone socialist. But, decried by the bosses and promoted with overblown radical rhetoric by his supporters, it became a rallying point for workers in NSW and across the country. Lang seemed to be the only Labor premier prepared to resist austerity.

Lang split from federal Labor, taking with him the bulk of Labor supporters and affiliated unions in NSW. The only significant support for the federally recognised party in NSW came from the right-wing AWU.

Lang, however, was attempting to have it both ways. He, like the other premiers, signed the hated Premiers Plan and cut government workers’ wages. But faced with a groundswell of left-wing pressure from below, Lang also moved to block evictions of tenants and did not compel the unemployed to work for the dole.

Working-class support for radical socialist ideas well to the left of the Lang Plan was surging. The 1930 NSW Labor conference authorised the formation of a Socialisation Committee to promote the goal of “socialism in our time”.

Lang initially did not see the Socialisation Committee as a threat and was prepared to allow Labor activists to engage in a bit of “harmless” socialist rhetoric. However, Socialisation Units attached to party branches rapidly proliferated, drawing in large numbers of previously unaffiliated workers.

By early 1931 there were 97 Socialisation Units and by late 1932 almost 180. At the 1931 Labor conference, supporters of the units voted up a motion calling on the next Labor government to implement “socialism within three years” with wide-scale nationalisations of industry under workers’ control.

Lang’s machine now recognised the threat and went into overdrive to have the motion reversed the next day and launched a campaign to clamp down on and eventually destroy the Socialisation Units.

The core leaders of the Units were not revolutionaries but left-wing reformists who believed that Labor could be won to support a parliamentary road to socialism. They were naive about the scale of opposition that that they would face within the Labor Party—not just from Lang, but from the left-talking but actually pro-capitalist union bureaucrats who dominated the party.

The workers who formed the base of the Socialisation Units were quite different to their leaders. Many of them still had illusions in Lang, but they were moving sharply to the left and were open to the argument that capitalism needed to be overthrown by revolutionary action.

The potential existed for a split from Labor and the formation of a sizeable revolutionary socialist party. That potential was to a large extent stifled by the utterly sectarian approach of the thoroughly Stalinised Communist Party.

Following the Stalinist line from Moscow, the CPA denounced Lang as a “social fascist”. The left-wing leaders of the Socialisation Units and at times even rank-and-file members of the units were abused as “left social fascists”. Even worse, the CPA refused to condemn and mobilise against the right-wing coup that overthrew Lang, taking a “plague on both your houses” line.

This appalling stance destroyed any possibility of winning over the mass of Socialisation Unit supporters to revolutionary politics. The CPA gained a mere handful of members from the units.

Lang undoubtedly was a charlatan who used populist rhetoric to cover up his essentially conservative pro-capitalist politics. But the illusions that masses of workers had in him could not be overcome by screaming that he was a social fascist when the rich and powerful were determined to bring down his Labor government and actual fascists were arming and mobilising in their tens of thousands on the streets against him.

Instead, revolutionary socialists needed to work alongside the working-class supporters of Lang and the Socialisation Units in the struggles in the unemployed movement, the unions, against the fascist New Guard and against the May 1932 coup; patiently but determinedly make the case for revolutionary politics and the need for a fighting alternative to Labor.