The 1967 referendum on Indigenous issues defied the propensity of referendums in Australia to fail. In fact, with 90.77 percent voting Yes, the referendum passed by a margin greatly surpassing all other successful ones.

The referendum altered the constitution to amend Section 51, which specified that the federal government could make laws with respect to the “people of any race, other than the Aboriginal race in any state, for whom it is deemed necessary to make special laws”—the words “other than the Aboriginal race in any state” were deleted. Section 127, which stipulated that in “reckoning the numbers of the people of the Commonwealth, or of a state or other part of the Commonwealth, Aboriginal natives shall not be counted”, was also deleted.

Much has been written about the formal constitutional implications of the 1967 vote, and a series of wrong ideas have been put forward regarding what was being voted on. For instance, Bain Attwood and Andrew Markus write in their book The 1967 referendum: race, power and the Australian constitution:

“Over the years it has been popularly claimed that the referendum gave Aboriginal people the vote, granted equal citizenship, repealed racially discriminatory laws, transferred Aboriginal affairs from the states to the Commonwealth, or that it did all of these things ... Yet, a reading of the Constitution would suggest that the changes endorsed in the referendum could have had none of these outcomes.”

The referendum has also been misrepresented as allowing Indigenous people to be counted in the census, but a recent article by academics Murray Goot and Tim Rowse in the Australian Journal of Politics and History shows that Indigenous people had been counted in every census since 1911. The referendum simply allowed these figures to be taken into account when calculating per capita grants to the states or determining the size of federal electorates.

This is all pretty irrelevant.

It was concerted political activism that gave popular meaning to the referendum far beyond changing the arcane words of the constitution. Campaigners turned it into a decision about rights for Indigenous people and the unacceptable situation they were in. The majority of people who voted Yes did so because they thought it would improve the lives of Aboriginal people.

Even the fairly anodyne official Yes case (there was no official No case because no parliamentarian would sponsor it) argued that the referendum, if successful, “will remove words from our Constitution that many people think are discriminatory against the Aboriginal people”.

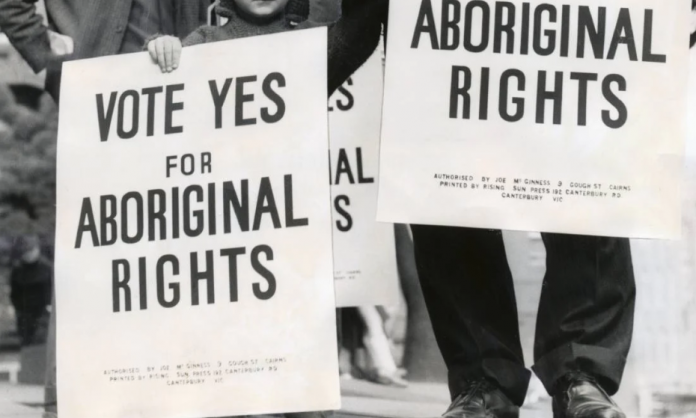

The main campaign organisation, the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islander (FCAATSI), produced leaflets that more bluntly proclaimed “Right wrongs. Write Yes for Aborigines on May 27”, and posters that urged people to “Vote Yes for Aboriginal rights”. That is what the vote was about.

A 1967 Gallup Poll of 1,200 voters conducted face-to-face a week before the referendum confirms this. In response to the question of what they thought the chief effect would be if the Yes vote won, 74 percent answered with reference to real improvements in the lives of Indigenous people: 38 percent mentioned “better opportunities, improved conditions, better housing, education”, 22 percent referred to “equal rights as citizens”, and 14 percent “higher morals, improved status, freedom”. Of the remaining 26 percent, a majority (16 percent) failed to express an opinion, 4 percent answered “bad effects, drinking, more discrimination”, and 6 percent “no effect”.

As none of the issues that animated the 74 percent of positive respondents had appeared in the official Yes case, the origins of their responses lie elsewhere—in the decade-long campaign for the referendum, and the political context of rising activism in the early 1960s. Renewed campaigning for Aboriginal rights intersected with international concerns about decolonisation, apartheid in South Africa and civil rights in the US. A growing youth radicalism and working-class militancy had come into full flower by the end of the decade.

It is worth enumerating the kind of things that had been law well into the period in which FCAATSI had been demanding a referendum.

In the early 1960s, most Indigenous people could not vote; receive welfare such as the age pension or unemployment entitlements; move freely from place to place; make decisions about their own lives such as where to live or work or who they could marry; be legal guardians of their own children; decide what they could do with their earnings; receive the award wages mandated for other workers; or drink alcohol.

By the time of the 1967 referendum, only Western Australia and Queensland retained explicitly discriminatory laws against Aboriginal people. In those two states, many Indigenous people still lived “under the Act”, meaning that the government still maintained control over many aspects of their lives.

The changes that took place owed much to the pressure of campaigning by both FCAATSI and many other Indigenous and non-Indigenous activists over the decade of the referendum campaign, and in many cases for decades before.

The referendum would not have been held without the pressure from fighters against Indigenous oppression over a much longer preceding period.

Groups such as the Aboriginal-Australian Fellowship in NSW took up petitioning for a referendum and the repeal of all discriminatory legislation in April 1957 at a meeting of 1,500 people—of whom about a third were Indigenous—at Sydney Town Hall. Within a year, the first national Aboriginal organisation, the Federal Council for Aboriginal Advancement (FCAA, changed to FCAATSI in 1964), was formed. It took up the demand initiated by the Aboriginal-Australian Fellowship.

The campaign for a referendum reflected the effects of the conservative and moderate nature of Indigenous activism during the 1950s. The focus on constitutional changes and empowering the federal government fitted with the cautious focus, especially during the height of the Cold War, of appealing to the United Nations and supposedly progressive Liberal politicians such as Paul Hasluck and William Charles Wentworth.

Despite these political limitations, they gathered 26,000 signatures on the original petition in 1958, and a new petition launched in 1962 gathered a further 103,000 signatures. Kath Walker (later known as Oodgeroo Noonuccal) became the campaign’s national coordinator and undertook an Australia-wide speaking tour, and a wide range of bodies were approached to support the campaign.

The focus placed on the constitutional changes proposed by the referendum was contested among Indigenous activists. As Attwood and Markus’ book points out: “Several Aboriginal leaders expressed serious criticisms of it in the lead-up to the poll”. For instance, “[Herbert] Groves expressed the desire of Aboriginal people ‘to be part and parcel of the community’ at the same time as he made it clear they wanted ‘to do this without losing [their] identity as Australian Aborigines’”. Aboriginal-Australian Fellowship member Ken Brindle later told activist Faith Bandler that he “couldn’t see how it would benefit us”. And yet they campaigned for the referendum to pass, as did many non-Indigenous activists, most importantly in the trade unions.

A range of left-wing unions dominated the FCAATSI affiliates list: the Building Workers’ Industrial Union, the Builders Labourers Federation, the Australian Railways Union, the metal industry unions such as the boilermakers and sheet metal workers, Miscellaneous Workers’ Union, teachers, plumbers and engine drivers, and some state Trades and Labour Councils.

By the end of 1964, some commentators were talking of a significant shift in workers’ consciousness, and that awareness of the demands of Indigenous people was one of the most important aspects of this. Many Aboriginal activists developed their political knowledge and gained organisational skills as working-class militants in unions. Some unions, generally Communist-led, had been gradually taking up Aboriginal issues in town and country since the early 1950s.

By early 1964, the Department of Labour was worried about the convergence of economic and political strikes. A report listed “unprecedented” strikes across a range of industries from the postal service to car manufacturing, and waterfront protests against apartheid as “just some” of the disputes in which “labour generally sought to exploit its strong position”. In 1964, reports of Black riots in the US over civil rights dominated the daily press. FCAATSI sharpened the international message: “A ‘No’ vote to the Aboriginal rights question will brand this country racist and put it in the same category as South Africa”.

The Menzies government resisted calls for a referendum for years. In 1965, it changed its tune, shortly after the Student Action for Aborigines’ Freedom Ride protest in country NSW exposed the reality of racism in a way that few previous protests had been able to.

When Harold Holt became prime minister in January 1966, he proposed a referendum the following year. It was all for show. Holt made it clear that his government had no plans to change the direction of Aboriginal policy. Its campaigning for the Yes vote was consequently lacklustre, to put it kindly.

By contrast, an enormous amount of work was put into the Yes campaign by progressive activists once the date was set in early 1967. The top official levels of the campaign were still lobbying politicians and contacting the media. But at the grassroots, the growing activism of the Freedom Ride and the Gurindji strike and rising union militancy positively infected the referendum campaign. Dozens, if not hundreds, of stop-work meetings were organised by trade unionists across the country, and petitions were gathered, meetings held, leaflets distributed, posters pasted up and badges sold.

Despite the limited nature of the demands raised by the referendum, the fact that more than 90 percent of the population voted Yes was a sign that mass sentiment had started to shift and that the radicalisation of the late ’60s was gaining momentum.

However, the constitutional change delivered nothing concrete to improve the lot of Indigenous people and this, combined with the Liberals’ refusal to grant even token land rights, revealed the limits of the referendum. Even Barrie Dexter, a member of the government’s Council for Aboriginal Affairs, which advised on Indigenous matters, conceded: “The mountain [of the referendum] gave birth to a mouse”. Gurindji leader Vincent Lingiari commented bluntly after the referendum: “Our citizenship has not brought us the opportunity to live a decent life”.

Political lessons were learnt. As Jordan Humphreys writes in Indigenous Liberation and Socialism: “The referendum campaign was in many ways the last roll of the dice for the older, more conservative, forms of activism around Aboriginal rights that had become hegemonic in the 1950s. Soon a new generation would take the lead”.

The resulting disillusionment among younger activists, combined with a deeper radicalisation fuelled by the anti-Vietnam War movement and 1969 general strike, led to more confrontational methods, such as those of the Australian Black Power Movement, and mass actions, such as the Aboriginal Tent Embassy.