Panama’s President Laurentino Cortizo has announced the closure of an environmentally destructive copper mine after the country’s Supreme Court ruled on 28 November that legislation granting the mine a 20-year concession was unconstitutional. The decision was greeted with jubilation by masses of protesters who had fought for weeks for this result.

The protest movement was sparked by the government’s decision, signed into law on 20 October, to renew the contract under which Canadian mining company First Quantum Minerals (FQM) operates the Cobre Panamá copper mine.

The contract was very favourable to the company. It promised that Panama would receive a minimum of US$375 million in annual revenue from the mine, but this pales in comparison to FQM’s likely profits, which totalled $1.1 billion last year. It also allowed the company to call on the government to seize any land it needed if it couldn’t convince the existing owners to sell—removing one of the last remaining points of leverage ordinary Panamanians had over the mine’s operations.

The Cobre Panamá mine plays a significant role in Panama’s economy. It contributes up to 5 percent of the country’s GDP, and 75 percent of its exports. The mine produces roughly 1.5 percent of the global copper supply. It directly employs 7,000 workers, but an estimated 40,000 people are employed in work related to the mine’s operation—making up roughly 2 percent of the entire Panamanian working class.

The mine has had a disastrous impact on the environment. According to environmental news site Mongabay, around 5,900 hectares of rainforest have been negatively impacted. Talking to Mongabay about the major rivers in the mine’s vicinity, local resident Estelina Santana said, “We have been told that the river is polluted and we prefer not to use it”.

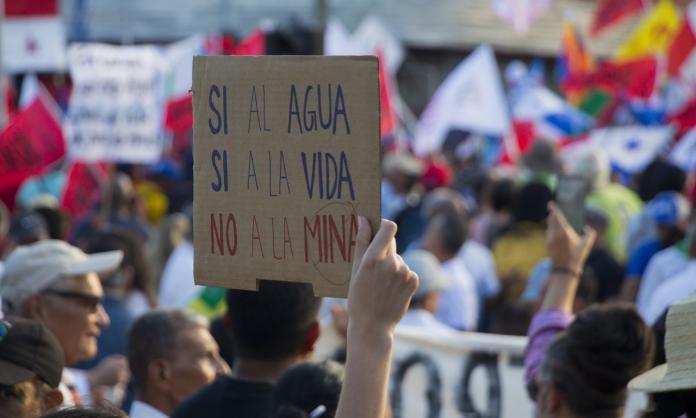

Immediately after the rushed backroom renewal of the mining concession, protesters took to the streets to oppose what they perceived as a sell-out by the government and to demand the contract be repealed. “Panamanians felt completely mocked”, one protester told the Washington Post.

Road blockades were established across the country, shutting down the movement of goods to the point that supermarkets began running out of stock. Ports were blockaded by small fishing boats. These actions were often led by the rural indigenous population. One fisher at a port near the mine explained to Reuters, “If this goes on a year, we will stay a year ... we know the area in which we are waging our war. We use ropes to make them back down and, well, threaten them”.

Indefinite strikes were called first by construction workers and teachers—members of the SUNTRACS and ASOPROF unions respectively. Their example was quickly followed by many other groups such as healthcare workers, nurses, doctors and social security workers. As the protest movement developed, the working class and the unions increasingly took on a leading role.

The strikes incorporated daily protests and mass marches, with videos posted online by SUNTRACS giving a good idea of why the workers joined the struggle. A construction worker in the Coclé region explained in a speech to his co-workers, “The fight we are waging in our country is not only against mining, it is with a system that is corrupted”.

It’s no coincidence that construction workers and teachers have led the way, or that they see the movement against Cobre Panamá as part of a wider struggle. Both sections of the working class have been at the forefront of battles against the Panamanian government in recent years, particularly since the election of President Cortizo in 2019.

Strikes by builders and teachers for better education funding, against lacklustre COVID-19 protections and for cost-of-living increases have drawn thousands into struggle alongside the unions. In particular, the battle over petrol prices in 2022 was a victory for the workers’ movement, with prices coming down by close to 50 percent by the end of a 27-day strike.

In taking up the anti-mining cause, workers helped to strengthen, cohere and drive the movement. As one teacher, in a video posted online by ASOPROF, put it at a march against the mine, “United we will win; the teachers are the people, and the people are with the teachers”.

The clearest indication of the power of this working-class-led movement was the response of the government, which quickly began to retreat. On 30 October, only ten days after the protests began, Cortizo announced a moratorium on all mining contracts and proposed to hold a referendum on the Cobre Panamá concession.

Unfortunately for Cortizo, this was rightly seen as a tactic to demobilise the workers, and the strikes continued. As one protester told Reuters, “People on the street have a very clear objective, which is to strike down the approved contract”. Having tried the stick, the government quickly learned that half a carrot wouldn’t work either.

Neither was simply waiting out the strikes and protests an option for Cortizo or FQM. The government faced the entire economy shutting down, with billions of dollars being lost due to delayed infrastructure projects and road and port blockades. FQM’s stock price plummeted nearly 50 percent. The port blockades made shipping copper from the Cobre Panamá mine nearly impossible, and the company announced a temporary suspension of all activities.

Under these conditions, on 28 November the Supreme Court made its ruling, and the government announced it would begin to close the mine. Rather than congratulating the government, however, SUNTRACS leader Saúl Méndez stated in a video made during protesters’ celebrations, “This is a popular triumph ... They did not give that ruling because they wanted it, they gave it because the people are in the street ... we have to finish facing down the whole agenda of the president, and we are going to with the same firmness, the same unity”.

This reflects the reality of a still unfolding situation in Panama—one in which the workers are on the front foot and could build on their victory. The teachers’ strike has only just concluded a week after the court’s ruling, with teachers winning back wages that had been withheld by the government during the protests in an attempt to break the strike. Construction workers have vowed to continue their protests until the mine is actually closed.

Additionally, the process of the mine’s closure raises new questions. FQM has launched a legal appeal to keep its mine open. At the same time, it has asked to have its obligations to contracted workers suspended. This would mean Cobre Panamá employees losing their jobs without pay or compensation—a move clearly aimed at raising tensions between mine workers and the anti-mine movement.

The largest mining union has opposed the protests and called for police repression. A significant minority of mine workers, however, have expressed solidarity with the movement. Building links between workers on a rank-and-file level and fighting for fair compensation and transition jobs for mining workers would significantly strengthen the workers’ position and keep the mining bosses and the government on the defensive.

Regardless of where the movement goes from here, what it has achieved so far should inspire all those fighting environmental destruction and the capitalist exploitation of nature and human labour alike. Solutions are often posed as coming from above. Movements are advised to be moderate and aim for compromise. In Panama, the opposite has been shown: intransigent struggle against capitalists and their representatives in government, particularly when based on the power of the working class, is the key to change.