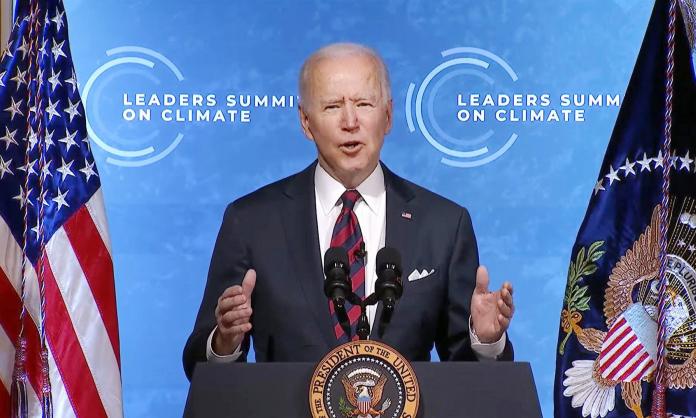

The world is in the grip of a “climate ambition” fad. At the Earth Day climate summit, initiated and hosted (virtually) on 22 April by US President Joe Biden, several countries made new emissions reduction pledges.

The US promised to cut emissions by at least half from 2005 levels by 2030, and reaffirmed Biden’s previous commitment to achieving net zero emissions from the electricity grid by 2035. Japan and Canada both announced updates to their existing pledges, Japan’s increasing to a 46 percent cut by 2030 (from 26 percent), and Canada’s to between 40 and 45 percent (from 30 percent). In addition to these new and updated emissions reduction pledges, South Korea promised to stop funding new coal projects overseas, and China announced its intention to begin reducing coal consumption from 2025.

In contrast to Donald Trump, Biden appears to believe not only that climate change is a real problem that needs addressing, but that the US should occupy a position of global leadership in this area. This has been enough to convince many media commentators that the world has finally turned a corner.

In her write-up on the summit, Guardian political editor Katharine Murphy effused that “the world has reset on climate action”. “Summit watchers”, she wrote, “witnessed a brisk competition between nations for the most ambitious emissions reductions pledges ... this felt like momentum. It felt like hope”. The world, according to Murphy, “will probably remain in a cycle of ambition while Biden is in the White House. Instead of a competition for who can avoid responsibility most cunningly, what’s under way now is a race to win the transition”.

As she often has in recent years, the inspirer of the school strike for climate movement, Greta Thunberg, offered a more sober assessment. In a letter published in Vogue, Thunberg argued:

“If you call these pledges and commitments ‘bold’ or ‘ambitious’, then you clearly haven’t fully understood the emergency we are in ... We’re not so naive that we believe that things will be solved by countries and companies making vague, distant, insufficient targets without any real pressure from the media and the general public. The gap between what needs to be done and what we are actually doing is widening by the minute.”

Thunberg is right to be sceptical. To date the only change that has occurred is a change in rhetoric. It’s clear the Biden administration believes that the appearance of taking action to address climate change is in the US’s interest. This no doubt relates, in part, to its effort to reassert itself on the world stage in the face of increasing competition from China. What’s less clear is the extent to which the rhetorical shift will translate into any real change on the ground. As Lisa Friedman and Coral Davenport noted in their coverage of the summit in the New York Times:

“Much of Mr. Biden’s promise to halve the country’s emissions remains wrapped up in the infrastructure plan, which includes the money and the policies to draw down carbon pollution, but has not yet been translated into legislation, much less found support from a divided Congress.”

Even if Biden’s US$2.3 trillion proposal, labelled the American Jobs Plan, were to be implemented in full—which is unlikely, given its eight-year time span and strong opposition from the Republicans—it’s unclear how it would translate into a 50 percent cut in emissions. As the title suggests, the plan’s primary aim isn’t to tackle climate change but to “create millions of good jobs, rebuild our country’s infrastructure, and position the United States to out-compete China”.

Much of the proposed spending in the plan is focused on renewing basic infrastructure like roads, bridges, ports and so on, which in the short term at least is likely to lead to a spike in emissions (from increased energy consumption, the production of large quantities of cement and so on). And even the “big ticket” items directly pitched as a response to climate change, such as the proposed US$178 billion investment in electric car manufacturing and infrastructure, won’t on their own result in the kind of rapid emissions reductions needed to achieve the 50 percent target by 2030.

A lot seems to rest on the assumption that technology will come to the rescue. Biden’s plan proposes a US$35 billion investment “in the full range of solutions needed to achieve technology breakthroughs that address the climate crisis”. These solutions, according to the plan, include “carbon capture and storage, hydrogen, advanced nuclear, rare earth element separations, floating offshore wind, biofuel/bioproducts, quantum computing, and electric vehicles”.

The Australian media’s response to the summit has focused on Scott Morrison’s status as a climate change pariah among a group of world leaders who, supposedly, have shown their determination to act. To Murphy he was “yesterday’s man, out of step with his peers both in tone and substance”.

Morrison is clearly out of step with Biden and others who’ve climbed aboard the “climate ambition” train when it comes to tone. Whether due to pressure from the right within his own party, or the view that any indication of increased ambition on climate change could cost the Liberals at the next election (or possibly a bit of both), he has proven unwilling even to undertake the relatively minor shift in rhetoric required to bring him into line with the new trend.

Morrison’s speech at the summit, and his address to a Business Council of Australia function a few days earlier, were carefully calibrated with a view to scoring points in the domestic culture war that has been raging since before the 2019 federal election—one that pits practical, salt of the earth types, in Morrison’s words “Australia’s industrial workhorses, farmers and scientists”, against the out-of-touch elites discussing climate change in “the cafes, dinner parties and wine bars of our inner cities”.

But when you look beyond the most provocative aspects of Morrison’s speeches, what he says has much in common with Biden’s plan. In his speech to the summit, for instance, Morrison boasted: “We are investing around $20 billion to achieve ambitious goals that will bring the cost of clean hydrogen, green steel, energy storage and carbon capture to commercial parity”. Taking into account the much smaller size of the Australian economy relative to the US, this investment compares favourably with the US$35 billion Biden has proposed to invest in similar “green” technologies.

Christopher Warren, writing in Crikey on 26 April, pointed to Morrison’s adoption of “the language of the global right’s latest talking point to manage the politics of transition: Prometheanism—the magic of technology will save us from the need for political action”. But Warren is wrong to suggest that this “Promethean” outlook is exclusive to the global right.

When, in his speech to the Business Council, Morrison said: “We are going to meet our ambitions with the smartest minds, the best technology and the animal spirits of our business community”, he could easily have been mistaken for a spokesperson for the Biden administration spruiking the American Jobs Plan. However much we may wish it were otherwise, Biden’s summit gave no indication that the “left” faction of the global ruling class is any less committed than the right to the idea that “the magic of technology will save us” from climate change.

The point here isn’t to claim that Morrison is doing better on climate change than appearances suggest. His performance over the past few weeks has cemented his spot as among the world’s most unabashed climate criminals—someone for whom even the sight of large swathes of his own country erupting in flames around him wasn’t enough to convince him to act. The point is that the rest of the world is hardly better, and to obscure this grim reality out of a desire to paint Morrison and Australia as radically “out of step” is not only misleading but also dangerous.

Even if the US and other countries were to meet their new, more ambitious, emissions reduction targets (and if the history of such promises is anything to go by, that is doubtful), it won’t be enough to head off the prospect of catastrophic, runaway warming. Already, we are seeing the possible beginnings of dangerous climate feedback loops—such as the release of large quantities of methane from melting Arctic permafrost.

The world doesn’t need any more ambitious targets for future emissions reductions, whether for 2030 or 2050. The path to hell, we might say, is paved with “climate ambition”. What we need if we’re to have any hope of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius is the kind of “rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society” that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change said were necessary in its 2018 report. Until we start to see such changes, we should have no faith in the pronouncements of politicians, however impressive they may sound.

Unpalatable as it may be to those desperate for a bit of hope, there’s little reason to think the Biden summit will prove any different to the many “historic” summits that have gone before. If we allow ourselves to be lulled into complacency by a few new targets and some idealistic sounding rhetoric, and into believing that the Australian government is somehow going to be “pulled into line” by Joe Biden or any other world leader, it will be yet another setback for a climate movement that’s proven all too susceptible to political spin.