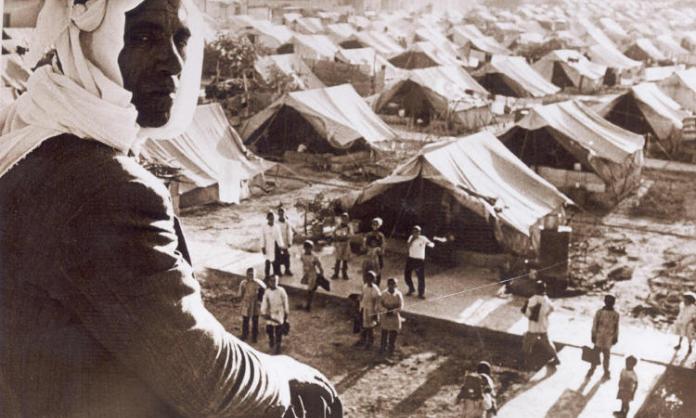

Al-Nakba (“the catastrophe”) refers to the destruction of Palestinian society that took place in 1948, when more than 500 villages were destroyed by Zionist militia and more than 1 million Palestinians were forcibly expelled from their homes—750,000 fleeing to neighbouring Arab states and the other 250,000 becoming internal refugees in the newly formed Israeli state.

Ever since, Israel has been an apartheid state that has used both military force and legally sanctioned discrimination to oppress the Palestinian people. Like other settler colonial states, Israel is primarily concerned with controlling territory and replacing the indigenous population with a settler population. As the late Australian theorist Patrick Wolfe noted, “settler colonialism destroys to replace”.

Zionism, the ideological foundation on which the Israeli state is built, emerged in the late 1800s in reaction to anti-Semitism and waves of anti-Jewish pogroms taking place in Europe. At the time, a section of the Jewish middle class concluded that anti-Semitism was an eternal and inescapable phenomenon as long as Jews lived among non-Jews. They believed that the only way to avoid it was to establish an independent state for the Jewish people. While the Zionist movement eventually settled on Palestine as the location for the new Jewish state, its leaders also considered a range of other countries, including Argentina, Turkey, Kenya, Angola and Uganda.

Regardless of the area chosen, Zionism’s founding father, Theodore Herzl, understood that it would be impossible to establish without the backing of the one of the major imperial powers. The Zionist movement, however, didn’t gain an imperial sponsor until in 1917, thirteen years after Herzl’s death, when the British government issued the Balfour Declaration, which affirmed that it would “view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people”.

Herzl also understood that, regardless of where the Jewish state was eventually established, it would be necessary to expel the existing indigenous population to make way for Jewish settler colonists. “When we occupy the land ... we shall try to spirit the penniless population across the border by procuring employment for it in the transit countries, while denying it any employment in our country”, Herzl wrote in an 1895 diary entry. “Both the [expropriation of property] and the removal of the poor must be carried out discreetly and circumspectly.”

Herzl here articulated two of Zionism’s central doctrines: exclusivist Jewish labour and “transfer”. As Palestinian historian Nur Masalha explains in Expulsion of the Palestinians, the concept of “transfer” within Zionist ideology came to be “a euphemism denoting the organised removal of the indigenous population of Palestine to neighbouring countries”. Moreover, he notes, it “occupied a central position in the strategic thinking of the leadership of the Zionist movement and the Yishuv [the Jewish population in Palestine prior to the founding of Israel] as a solution to the ‘Arab question’ in Palestine ... Virtually every member of the Zionist pantheon of founding fathers and important leaders supported it and advocated it in one form or another”.

Prior to the 1890s, Jewish people made up less than 4 percent of the population of Palestine, while Palestinian Arab Muslims and Christians made up the overwhelming majority. It was therefore essential, if the Zionist project were to succeed, to change the demographic balance. Over the next 50 years, mass Zionist immigration to Palestine increased the Jewish settler population to approximately one-third of the overall population. The Zionist movement also bought land from Palestinian and Arab landowners, establishing dozens of colonies and expelling the Palestinian tenant farmers and their families who had worked the land for centuries.

It soon became clear that very few Palestinians had any interest in selling their land to the colonists. By 1947, Jewish settlers had succeeded in purchasing just 7 percent of privately owned land in the territory. However, as Patrick Wolfe notes in his 2016 book Traces of History, even this limited acquisition of territory allowed the Zionist movement “to establish a colonial beachhead” in Palestine from which it could carry out the mass, violent expulsion of most of the Palestinian Arab population, expropriate the lands which they once occupied and establish the state of Israel.

As Zionist settler colonialism intensified, political violence in 1920, 1921, 1929 and 1933 erupted as tensions between the Jewish Zionist settlers and the Palestinian Arab population boiled over. In 1936, Palestinians began a three-year anti-colonial revolt. Combining non-violent civil disobedience, general strikes and armed struggle, tens of thousands of Palestinian Arabs from all classes mobilised to throw off the shackles of British imperialism and Zionist settler colonialism.

During the revolt, British mandate police stations and government buildings were targeted; British convoys were attacked; roads, railroads and telegraph lines were cut; and trains and oil pipelines were blown up. More than 5,000 Palestinians were killed by British troops.

The British authorities also carried out collective punishment against whole Palestinian villages. This included bombing several villages out of existence, demolishing houses, enacting curfews, outlawing Palestinian political parties and associations, deporting or exiling their leaders and banning public protests. Hundreds of Palestinians were also convicted by British military courts; more than 50 were hanged and 2,500 detained in internment camps. By late 1938, Palestine was under a state of siege. It took more than 20,000 British and 15,000 Zionist troops to finally put the revolt down in 1939.

By the end of the uprising, the Zionist movement was stronger than it had been in 1936, having increased its military capacity due to its collaboration with Britain to suppress the revolt. Between 1940 and 1945, Zionist leader David Ben-Gurion continued to strengthen and expand the military capabilities of the Zionist movement in Palestine, while supporting Britain’s war efforts in Europe.

With the Palestinian national movement crushed, the leaders of the Zionist movement also began final preparations for the creation of the Zionist state, including creating a detailed registry of every Arab village in Palestine. This registry, known as the Village Files, was compiled by the Jewish National Fund, which was responsible for settling Jewish colonists in historic Palestine. Today, the fund remains one of the key tools used by the Zionist movement to enable the colonisation of Palestine.

According to Israeli historian Ilan Pappe, although the Village Files recorded the location of the villages, access roads, land quality and other socio-cultural information such as the names of village leaders, religious affiliations of the inhabitants and their main sources of income, they were not simply an “academic exercise in geography”.

Pappe explains in his 2006 book The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine that the files also included “an index of hostility” towards the Zionist project based on whether the villages had participated in the 1936-39 revolt. Accompanying the index was a series of lists, which identified individuals and families who had fought against the British and the Zionists during the revolt or had been involved in the Palestinian national movement in any capacity.

According to Pappe, these lists, along with lists added in 1947 detailing “wanted” persons, were used in 1948 by Zionist militias as they seized control of and occupied Palestinian villages. Any Palestinians on the lists were immediately identified and “shot on the spot”.

As the war in Europe drew to a close in 1945, the Zionists under the leadership of Ben-Gurion enacted a new strategy, believing they were now militarily and demographically strong enough to need no longer the imperial backing of Britain. Over the next three years, Zionist militias attacked not only Palestinian Arabs but also British troops and infrastructure, including the terrorist bombing of Britain’s administrative headquarters in the King David Hotel in 1946, resulting in the death of 91 government officials, soldiers, police and office workers.

Zionist terrorist attacks on both British infrastructure and Palestinian villages escalated further after 29 November 1947, when the United Nations announced its plan to partition Palestine. The UN plan allocated 55 percent of Palestine to the Zionist movement, despite Palestinian Arabs making up two-thirds of the population.

Between December 1947 and March 1948, Zionist militias stepped up their terrorist bombings of Palestinian neighbourhoods and villages. Among the attacks ordered by Ben-Gurion at the end of January 1948 was the destruction of the Sheikh Jarrah neighbourhood in Jerusalem. On 7 February, a week after the attack, Ben-Gurion also visited the Palestinian village of Lifta on the outskirts of Jerusalem, which had been destroyed in early January. According to Pappe, after the visit, Ben-Gurion “jubilantly recounted” to other leaders of his political party:

“In many Arab neighbourhoods in the west [of Jerusalem] you do not see even one Arab ... what happened in Jerusalem and in Haifa—can happen in large parts of the country ... If we persist it is quite possible that in the next six or eight months there will be considerable changes in the country, very considerable, and to our advantage. There will certainly be considerable changes in the demographic composition of the country.”

Throughout February 1948, the Zionist militia under Ben-Gurion’s command continued to terrorise Palestinian villages, expelling their residents. In March, Ben-Gurion finalised Plan Dalet, the Zionist movement’s blueprint for the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians. Pappe notes in his book that, at the beginning of April, “each brigade commander received a list of the villages or neighbourhoods that had to be occupied, destroyed, and their inhabitants expelled”.

Following Ben-Gurion’s formal declaration of the establishment of Israel on 14 May, his new government set up an unofficial “Transfer Committee” to oversee the continued ethnic cleansing. In The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited, Israeli Zionist historian Benny Morris notes that a 5 June memorandum issued by the Transfer Committee argued that “the uprooting of the Arabs should be seen as a solution to the Arab question” and proposed “preventing Arabs from returning to their places” by carrying out the “destruction of villages as much as possible during military operations” and the “settlement of Jews in a number of villages and towns”.

By the time Zionist forces finished implementing Plan Dalet in January 1949, the Zionist movement had taken control of 78 percent of historic Palestine and expelled 1 million Palestinians from their homes.

Since 1948, Israel has continued to expand, annexing more and more Palestinian land. In 1967, it took East Jerusalem, Gaza, the West Bank and the Golan Heights, ethnically cleansing a further 350,000-400,000 Palestinians from their land and homes. Since then, Israel has established more than 130 colonies in the occupied West Bank and East Jerusalem, while another 100 wildcat (unofficial) colonies have been established independently. More than 600,000 Israeli colonists are living in the Occupied West Bank and East Jerusalem in contravention of international law.

For Palestinians, the Nakba of 1948 never ended.