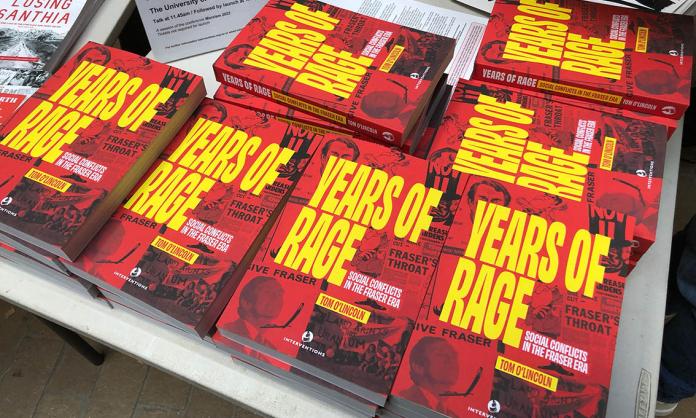

It is a real treat to have a new edition of Socialist Alternative member Tom O’Lincoln’s 1993 book, Years of Rage: Social Conflicts in the Fraser Era. While the text remains basically unchanged, as it did in the 2012 re-issue, this edition by left-wing publisher Interventions is significantly expanded and enlivened by the addition of photos, leaflets and posters from the time, and a twelve-page afterword by Rick Kuhn.

Years of Rage remains the best account of the Fraser era, all the better for being, as its publishers put it, “a partisan and Marxist history” whose author’s “sympathies lie with the militants and activists fighting for a better world”.

While framed by the undemocratic dismissal of the Whitlam Labor government in 1975, which brought Malcolm Fraser and the Liberal Party to power, and Fraser’s own electoral demise in 1983, the book is anything but electoral in focus. It pulses with the life of the class struggle (from both the workers’ and the bosses’ side), with the fight back of oppressed groups—including those for Aboriginal land rights, LGBTI and abortion rights—with other political campaigns such as those against uranium mining or for civil liberties and the right to march in Queensland. Most importantly, it provides both an explanation for these struggles and an insight into their political strengths and weaknesses.

The dismissal of the Whitlam government on 11 November 1975 provoked a massive working-class response of strikes, walkouts and street protests. O’Lincoln reminds us why the ruling class got rid of Whitlam—not because he was too radical but because his government could not move fast enough to dampen working-class militancy to keep the bosses happy.

Following the dismissal of Whitlam by Governor-General John Kerr, the December 1975 election confirmed Fraser in office after Labor and the Australian Council of Trade Unions told the working class to “cool it”—to maintain their rage for the ballot box—and ran an election campaign not about democracy but about wage restraint and sound economic management.

Nonetheless, the dismissal left a residue of profound working-class hatred for Fraser, “Kerr’s cur”, during his seven years in office.

Yet from the ruling class’s point of view, the Fraser government never produced the goods. The working class, though battered by the Kerr coup, high unemployment and several important industrial defeats in 1976 and 1977, managed to regroup. From 1979 to 1981, the strike rate soared, destroying business hopes that the Liberals could rein in the unions. When the strike wave was followed by another serious recession, the government’s fate was sealed.

Years of Rage outlines Fraser’s initial successes for the capitalists. He gutted Medibank despite a 24-hour general strike on 12 July 1976—the biggest in Australian history. But from the latter part of 1978, unions began to reassert themselves industrially. The fight over wages re-galvanised working-class struggle, destroying the wage-cutting indexation system and unleashing a strike wave. Average weekly earnings increased by 16 percent over two years.

When this successful strike wave was followed by a sharp recession in 1982, the ruling class had had it with Fraser. ACTU leader Bob Hawke’s regular pleas to the Fraser government to include the union leaders in some form of consensus economic management now looked more attractive to the bosses.

The strengths of the book lie not simply in the wealth of vibrant detail with which O’Lincoln conveys the struggles of the era. The chapter “Issues on the left” is particularly important. As well as explaining the shift away from radicalism by many on the left, from academic Marxists to feminists, O’Lincoln also provides an analysis of why, despite the fact that workers were still capable of great militancy, the main political beneficiaries were not the left but the political centre—the ALP leaders who sought a new era of class collaboration.

He locates this in the return of economic crisis to world capitalism in the 1970s, and the political responses to it on the left. From Labor, it was straightforward: don’t go too far too fast, prove to the bosses you can be a safe pair of hands in attacking the working class as the only way to get re-elected.

But electoralism is not the only form that reformism takes. The 1979-81 wages push took place during an economic boom centred on the resources sector, which came to a sudden halt in 1982 as commodity prices fell. Unemployment went from less than 6 percent to more than 10 percent. Most of the union movement capitulated to the argument that recession and unemployment stemmed from “excessive” wage claims.

The necessary anti-capitalist argument, that economic crises stemmed not from workers trying to get what was theirs, but from the logic of capitalist competition itself, was made only by small groups of revolutionaries without significant influence in the workers’ movement.

The Fraser years showed the continued economic strength of the organised working class in Australia. But they also showed the political weaknesses of the left. As O’Lincoln writes at the end of the book:

“A fairly large minority of workers went into the mid-1970s with an ill-defined but genuine belief that the crisis of capitalism was the appointed time for labour to impose its will on a society whose old order was proving bankrupt. A sizeable minority of political activists held similar views. But in the absence of a mass political movement determined to pull these currents together and lead a struggle for power, this fragmented vanguard could not ... prevail.”

Whether future years of rage end more favourably depends on socialists’ ability to gain a wider hearing. This book will help us.