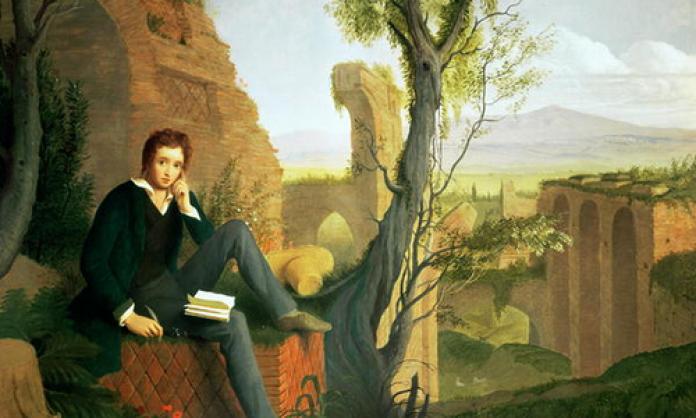

Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822) was one of the major English Romantic poets—and arguably the greatest. The critic Harold Bloom described him as “a superb craftsman, a lyric poet without rival, and surely one of the most advanced sceptical intellects ever to write a poem”. But he was much more than that: he was also a passionate revolutionary.

Shelley’s short life spanned a crucial period in history. He was born at the height of the French Revolution. Like many of his generation, Shelley was inspired by the revolution and the ideas of the Enlightenment. He was an avowed atheist as well as a republican and democrat. Unlike most of his peers, Shelley remained true to these beliefs.

This was also a time of social crisis and extreme repression in England. Shelley’s life coincides fairly closely with the period covered in historian E.P. Thompson’s book The Making of the English Working Class. The industrial revolution had transformed society. Yet capitalism had brought nothing but increasing misery to workers, first driving them off the land to work in factories under horrific conditions, then depriving them of their livelihood by replacing them with machines. A vicious Tory government conducted a reign of terror against workers and the poor, savagely repressing moves for parliamentary reform, outlawing trade unions and smashing the Luddite revolts.

Shelley hated all forms of oppression and championed the cause of workers, women and the Irish. This earned him the undying hatred of the ruling class. One reviewer of the time summed up why: “Mr Shelley would ... would abolish the rights of property ... he would overthrow the constitution ... he would pull down our churches, level our Establishment, and burn our bibles”. When he died in a boating accident, one British newspaper gloated: “Shelley, the writer of some infidel poetry, has been drowned. Now he knows whether there is a God or no”.

So it’s not surprising that much of Shelley’s writing was deemed “seditious” and duly suppressed. His political essay, “A Philosophical View of Reform”—which argued that insurrection was justified as a response to tyranny—was not published until 1920. Many of his poems remained unpublished during his lifetime, or only saw light of day in underground editions. But radical publishers such as Richard Carlile kept his work alive, despite persecution and imprisonment. Though spurned by establishment critics who condemned his political, social and religious views, Shelley’s poetry gained a wide audience in radical circles and influenced poets sympathetic to the workers’ movement, such as William Morris.

Although he came from a privileged and wealthy background (his father was a Whig MP), Shelley was a rebel from an early age. Sent to Eton in 1804, he refused to participate in “fagging”—a traditional practice in British public schools that forced younger pupils to act as personal servants to the eldest boys, and often involved physical and/or sexual abuse. As a result, he was subjected to severe bullying. Despite this, the young Shelley revealed prodigious intellectual talents. He read voraciously and his wide range of interests included philosophy, natural history and science. Even before leaving Eton in 1810, Shelley had written two novels, a verse melodrama and (with his sister Elizabeth) a collection of poems.

After Eton, Shelley attended University College, Oxford. But his time there was cut short. Together with his friend Thomas Jefferson Hogg, he wrote a series of political poems and tracts under the pseudonym Margaret Nicolson (a washerwoman who had tried to assassinate the king). They also collaborated on an essay, “The necessity of atheism”, published anonymously (as it risked prosecution for religious libel) in 1811. Shelley sent a copy of this pamphlet to all the bishops and heads of colleges at Oxford. Called to appear before the college’s fellows, he was expelled for “contumaciously refusing to answer questions” and for “repeatedly declining to disavow” the pamphlet.

Living in Ireland in 1812, Shelley published three political tracts and delivered a speech calling for Catholic emancipation, the repeal of the Acts of Union and an end to the oppression of the Irish poor. These subversive activities were reported to the Home Office, which placed him under surveillance.

Shelley’s personal life was marred by family crises, financial difficulties and ill health. He was constantly vilified for his atheism, political views and defiance of social conventions, his work was subject to censorship, and at times he faced imprisonment for his political agitation. In 1818, Shelley and his second wife, Mary (author of Frankenstein), left England—partly for health reasons, but also to escape its “tyranny civil and religious”. They lived in Italy until Shelley’s untimely death four years later. Yet in the space of little more than a decade, he had produced an enormous body of work, a legacy that continues to inspire today.

Karl Marx was a huge admirer. “He declared that those who loved and understood [Shelley and his friend and fellow-poet Byron] must consider it fortunate that Byron died at the age of 36, for had he lived out his full span he would undoubtedly have become a reactionary bourgeois, while regretting on the other hand that Shelley died at the age of 29, for Shelley was a thorough revolutionary and would have remained in the van of socialism throughout his life”, his biographer Franz Mehring wrote.

Many of Shelley’s poems were very long, and we can only provide some samples here. But hopefully the following notes and excerpts will whet the appetite and inspire readers to seek them out.

Queen Mab (1813)

This early poem, written during the Luddite uprising, was ruled by the High Court to be both blasphemous and seditious. In it he used a woman to represent the revolutionary spirit, a device he repeated in later works. In Queen Mab, a Fairy Queen takes the spirit of a young girl on a trip to the stratosphere and shows her the earth with all its horrors of war and exploitation. The Queen vents her (and Shelley’s) fury at the villains responsible for them:

Those gilded flies

That, basking in the sunshine of a court,

Fatten on its corruption! what are they?—

The drones of the community; they feed

On the mechanic’s labour ...

Whence, thinkest thou, kings and parasites arose?

Whence that unnatural line of drones who heap

Toil and unvanquishable penury

On those who build their palaces and bring

Their daily bread?—From vice, black loathsome vice;

From rapine, madness, treachery, and wrong;

From all that genders misery, and makes

Of earth this thorny wilderness; from lust,

Revenge, and murder ...

But the queen also expresses hope for the possibility of a better world:

But hoary-headed selfishness has felt

Its death-blow and is tottering to the grave;

A brighter morn awaits the human day,

When every transfer of earth’s natural gifts

Shall be a commerce of good words and works;

When poverty and wealth, the thirst of fame,

The fear of infamy, disease and woe,

War with its million horrors, and fierce hell,

Shall live but in the memory of time ...

This poem had an enormous impact: cheap underground editions were snapped up by small working-class societies and illegal trade unions, passed from hand to hand and read aloud at workers’ meetings. Workers who couldn’t read learned key passages by heart.

George Bernard Shaw wrote that Queen Mab was “the Chartists’ bible”. Chartism was a mass working-class movement which emerged in 1836 in London and spread rapidly across Britain, following the Great Reform Act of 1832, which granted voting rights to the property-owning middle classes. The aim of the Chartists was to gain political rights for the working class. The demands of the People’s Charter included a vote for all men over 21, secret ballots, no property qualification to become a member of parliament and payment for MPs, and annual elections for Parliament.

The Revolt of Islam (1818)

Shelley was well ahead of his time with his advocacy of women’s rights and advanced ideas about relationships between the sexes. The Revolt of Islam, his longest poem at 4,818 lines, is dedicated to his wife Mary in appreciation for her love, comradeship and contribution to his art. The plot centres on two characters, Laon and Cythna, who initiate a revolution against the despotic ruler of Argolis (Greece), then under Ottoman rule. It deals with themes of liberation, revolutionary idealism and sexual equality. Mary Shelley wrote:

“[Shelley] chose for his hero [Laon] a youth nourished in dreams of liberty, some of whose actions are in direct opposition to the opinions of the world, but who is animated throughout by ... a resolution to confer the boons of political and intellectual freedom on his fellow-creatures. He created for this youth a woman [Cythna] such as he delighted to imagine—full of enthusiasm for the same objects; and they both, with will unvanquished and the deepest sense of the justice of their cause, met adversity and death.”

Many who have never heard of Shelley will be familiar with the famous question asked by Cythna: “Can man be free if woman be a slave?”

Ozymandias (1818)

Shelley despised monarchs and despots and wrote numerous poems attacking them. This sonnet is a warning to tyrants that their power and rule cannot last.

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. Near them on the sand,

half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown

And wrinkled lip and sneer of cold command

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal these words appear

“My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!”

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

The Mask of Anarchy (1819)

This poem was one of several written in the white heat of Shelley’s fury and outrage over the Peterloo massacre of August 1819. Sixty thousand peaceful protesters had gathered in St Peter’s Field in Manchester to demand the reform of parliamentary representation. Cavalry troops charged into the crowd, killing fifteen. By “anarchy”, Shelley meant the chaos of tyranny, a society in which only a few at the top can have any control over their lives. Castlereagh, Eldon and Sidmouth were reactionary government ministers.

As I lay asleep in Italy

There came a voice from over the Sea,

And with great power it forth led me

To walk in the visions of Poesy.

I met Murder on the way—

He had a mask like Castlereagh—

Very smooth he looked, yet grim;

Seven blood-hounds followed him:

All were fat; and well they might

Be in admirable plight,

For one by one, and two by two,

He tossed the human hearts to chew

Which from his wide cloak he drew.

Next came Fraud, and he had on,

Like Eldon, an ermined gown;

His big tears, for he wept well,

Turned to mill-stones as they fell.

And the little children, who

Round his feet played to and fro,

Thinking every tear a gem,

Had their brains knocked out by them.

Clothed with the Bible, as with light,

And the shadows of the night,

Like Sidmouth, next, Hypocrisy

On a crocodile rode by.

And many more Destructions played

In this ghastly masquerade,

All disguised, even to the eyes,

Like Bishops, lawyers, peers, or spies.

Last came Anarchy: he rode

On a white horse, splashed with blood;

He was pale even to the lips,

Like Death in the Apocalypse.

And he wore a kingly crown;

And in his grasp a sceptre shone;

On his brow this mark I saw—

“I AM GOD, AND KING, AND LAW!” …

The poem concludes with one of the most stirring calls to arms ever written:

Rise like Lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number,

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you—

Ye are many—they are few.

Declaring “England in 1819” as its poem of the week in February 2009, the Guardian commented: “You can almost hear the angry howl of an invisible people rising up against their useless royal family and treacherous government ... How pertinent those lines about the rulers ‘who neither feel, nor see, nor know’ are to England in 2009”.

An old, mad, blind, despis’d, and dying king,

Princes, the dregs of their dull race, who flow

Through public scorn—mud from a muddy spring,

Rulers who neither see, nor feel, nor know,

But leech-like to their fainting country cling,

Till they drop, blind in blood, without a blow…

Another poem from 1819, “Song to the Men of England”, is remarkable for its understanding and articulation of exploitation, as well as the alienation suffered by workers:

Men of England, wherefore plough

For the lords who lay ye low?

Wherefore weave with toil and care

The rich robes your tyrants wear?

Wherefore feed and clothe and save,

From the cradle to the grave,

Those ungrateful drones who would

Drain your sweat—nay, drink your blood?

Wherefore, Bees of England, forge

Many a weapon, chain, and scourge,

That these stingless drones may spoil

The forced produce of your toil?

Have ye leisure, comfort, calm,

Shelter, food, love’s gentle balm?

Or what is it ye buy so dear

With your pain and with your fear?

The seed ye sow another reaps;

The wealth ye find another keeps;

The robes ye weave another wears;

The arms ye forge another bears.

Sow seed,—but let no tyrant reap;

Find wealth,—let no imposter heap;

Weave robes,—let not the idle wear;

Forge arms, in your defence to bear.

Shrink to your cellars, holes, and cells;

In halls ye deck another dwells.

Why shake the chains ye wrought? Ye see

The steel ye tempered glance on ye.

With plough and spade and hoe and loom,

Trace your grave, and build your tomb,

And weave your winding-sheet, till fair

England be your sepulchre!

Ode to the West Wind (1819)

As an exile in Italy, Shelley was isolated from a movement that in any case was very much in its infancy. At times he was plunged into despondency and a sense of helplessness when confronted with the power and savagery of the ruling class, as he was after Peterloo. “I wonder why I write verses, for no one reads them”, he wrote to a friend. He wrestled with all sorts of doubts and contradictory ideas about how change could come about, but he always took the side of the oppressed and ultimately came down on the side of revolution rather than mere reform. As Mary Shelley put it: “He believed that a clash between the two classes of society was inevitable, and he eagerly ranged himself on the people’s side”.

“Ode to the West Wind” is often presented in sanitised anthologies as a lyrical nature poem. But in fact it’s deeply political, beginning as an expression of Shelley’s struggle against pessimism and despair. The wind is first presented as a chaotic force, spreading plague and destruction:

O wild West Wind, thou breath of Autumn’s being,

Thou, from whose unseen presence the leaves dead

Are driven, like ghosts from an enchanter fleeing,

Yellow, and black, and pale, and hectic red,

Pestilence-stricken multitudes ...

But the wind has another character; it preserves as well as destroys. And it carries with it the seeds of change:

... O thou,

Who chariotest to their dark wintry bed

The winged seeds, where they lie cold and low,

Each like a corpse within its grave, until

Thine azure sister of the Spring shall blow

Her clarion o’er the dreaming earth, and fill

(Driving sweet buds like flocks to feed in air)

With living hues and odours plain and hill:

Wild Spirit, which art moving everywhere;

Destroyer and preserver; hear, oh, hear!

The poem goes on to talk of the “approaching storm”, the “black rain, and fire, and hail”—a metaphor for revolution—that will shatter the “old palaces and towers”. Shelley then reflects on his own feelings of impotence and inability to affect the wind’s tempestuous course. His biographer Newman Ivey White perceptively wrote that Shelley here was confronting “a deep realisation of the disparity between the tremendous thing that must be done and the inadequacy of one mind and body to do the task”.

... If even

I were as in my boyhood, and could be

The comrade of thy wanderings over Heaven,

As then, when to outstrip thy skiey speed

Scarce seemed a vision; I would ne’er have striven

As thus with thee in prayer in my sore need.

Oh, lift me as a wave, a leaf, a cloud!

I fall upon the thorns of life! I bleed!

A heavy weight of hours has chained and bowed

One too like thee: tameless, and swift, and proud.

But the poem ends with an appeal to the wind to lift him up, to spread his words and turn them into a rallying cry for humanity:

... Be thou, Spirit fierce,

My spirit! Be thou me, impetuous one!

Drive my dead thoughts over the universe

Like withered leaves to quicken a new birth!

And, by the incantation of this verse,

Scatter, as from an unextinguished hearth

Ashes and sparks, my words among mankind!

Be through my lips to unawakened earth

The trumpet of a prophecy!

The final words offer hope—no matter how bad things get, the struggle against injustice and for a better world is irrepressible, and as inevitable as the changing of the seasons:

... O, Wind,

If Winter comes, can Spring be far behind?