“If you don’t like it, move out.” This is the message from landlords to tenants who can’t afford rent increases amid a housing crisis that continues to worsen.

Australia already had one of the most unaffordable housing markets in the world, but in the last twelve months rents have soared across the country. In the capital cities, they increased by an unprecedented 17.6 percent last year, the steepest annual rise ever recorded. In some areas, 20-40 percent hikes are the norm. Vacancy rates have dropped to 1.8 percent in Sydney, 1.7 percent in Melbourne and as low as 0.6 percent in Hobart and Adelaide.

The average renter is now paying $3,000 a year more; overall, tenants paid an extra $7.1 billion in rent in 2022. Only 0.1 percent of rental properties are affordable for a person on a disability support pension, and almost half of low-income households are paying more than 30 percent of their income in rent. More than 163,000 people are on social housing waitlists, while 164,000 properties in Sydney and 1 million across Australia sit empty. And all of this is in the context of a general cost of living crisis, with wages stagnating while the price of essential goods goes up and up.

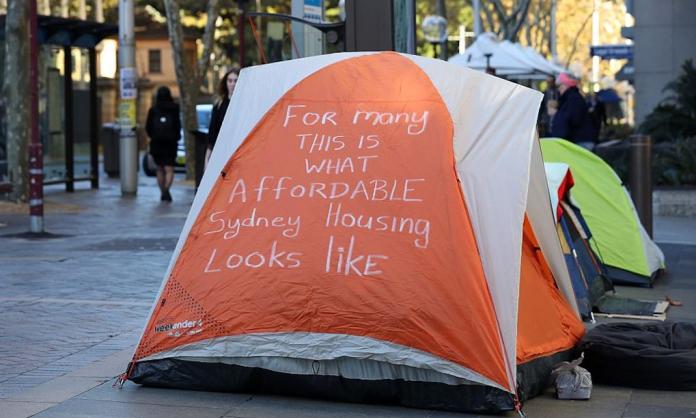

Behind the figures is the brutal effect on the lives of working-class people. Some are living in tents because they can’t get places to live. Others are being handed eviction notices with rent increases to make sure they don’t use the few legal rights they have to challenge the increase. Families are turning up to inspections to find 100 others competing for the same property, and being told to lie about the number of kids they have to improve their chances of being approved.

In Sydney, tarpaulin-covered balconies are being advertised for $300 a week.

The immediate cause of the spike in rents is landlords cashing in on low vacancy rates and the associated increase in demand. Rental demand is increasing because of the unaffordability of home ownership, the lack of public housing and the return of international students to universities. With so many people desperate for a home, landlords have been able to impose rent increases that far outstrip inflation.

The bigger picture is the effect of massive speculation in the property market over the last three decades. Investors accounted for 55 percent of purchases in 2015, up from 20 percent in 1993. Rich investors benefit from rising land values and are given huge financial incentives—basically government handouts—through negative gearing and capital gains tax exemptions, all in addition to collecting more than $43 billion in rent every year.

Behind all of this is profit. Housing is provided according to what will make the rich richer, not to satisfy people’s most basic need for a home.

But while the rich cash in and renters go to the wall, governments are doing nothing to address the crisis. Federal Labor’s plan to boost housing supply is simply a cash handout to developers for properties that will be sold at market prices and that would have built in any case.

Its “big” promise to build 30,000 social and affordable housing properties over five years is an insult when experts say that 1 million public and affordable homes will be needed in the next decade. The houses that the government does build will be funded largely through speculation on the stock market and will be managed by private NGOs.

In New South Wales, Labor is heading into next month’s state election promising a change to no-fault evictions but otherwise offering nothing more than a tweak to the administration of public housing. In Victoria, Daniel Andrews’ much vaunted $5.3 billion “Big Housing Build” has been little more than a massive sell-off of public land to private developers, with only marginal increases in net housing stock at a cost much higher than if the government had built the houses itself.

Though you wouldn’t know it from the politicians, there is a lot that could and should be done now to make housing more affordable. Rents should be capped and reduced to a level that people can afford. Unfair evictions should be prevented, and vacant properties should be seized to house people on the social housing waiting lists. Negative gearing and capital gains tax exemptions should be abolished, and the revenues gained should be used to build the 1 million public housing properties that are needed to provide affordable homes and take pressure off the rental market. The private market in student housing should be shut down, and universities should be forced to provide affordable housing to their domestic and international students.

These measures are all possible, but we can’t expect that any of it will happen without a fight—a fight that rejects the logic of the market and puts people before the profits of the rich.