Ten beautiful days of struggle have won the students of South Africa a great victory. They have forced the African National Congress (ANC) government to declare that university fees, which were set to rise by up to 11 percent, will be frozen in 2016.

Beginning 14 October with a demonstration at Wits University in Johannesburg, students across the country rose up against the proposed hikes, which would have forced tens of thousands of students out of the system, joining the millions who are already locked out because of the cost and difficulty of sustaining themselves during their degrees.

[Read more: Ashley Fataar from Cape Town, "Fee protests point to a much deeper problem at South African universities"]

This was the biggest uprising of students since the fall of apartheid. From the elite universities such as Wits, Rhodes University in the Eastern Cape and the University of Cape Town (UCT), to the “historically Black universities” and polytechnics such as the University of Western Cape, the Cape Polytechnic University of Technology and Nelson Mandela’s alma mater, the University of Fort Hare, students took action. They rallied together using the hashtag #FeesMustFall to coordinate, communicate and publicise their cause.

Day and night, students held mass meetings on the campuses, occupied their administration buildings, and shut down the universities. At UCT, high school students came onto campus and joined with their older brothers and sisters.

As classes were cancelled, the activists organised teach-ins and made space to help their fellow students to swot towards their final exams. They cleaned up any mess created by their occupations: they knew that the burden would otherwise fall on low-paid campus cleaners who could, in the case of Black students, be their own mothers.

Although the protest movement mainly involved Black students, white students also took part – the economic situation is beginning to bite some of them too. On many occasions Black and white students linked arms in battles with the cops.

The student uprising shook up a layer of academics. While a minority attacked the students and the majority stayed quiet, an active minority came out in support. They issued a statement of solidarity, declaring that they stood alongside students in their fight for the democratisation of the universities. And they put their bodies on the line on one occasion, forming a human shield at the front of a demonstration by UCT students.

#FeesMustFall had an impact on wider society, becoming the talk of the country for a week. Even at the South African Fashion Show, models appeared on the runway carrying placards “#FeesMustFall” and “#NationalShutDown”.

The university administrations were caught flat-footed. For years fee increases have been introduced with relatively little resistance. Now things had blown up in their faces, thanks to the lead given by students at Wits. The vice chancellors had been used to private meetings with a few student union leaders. Now the students demanded that the VCs come down and meet them in public.

VCs at Wits and Rhodes sat amid crowds of students, vainly attempting to get them to accept increased fees. The Wits VC thought he might win them over with an offer to reduce the increase from 10.5 percent to 6 percent. No chance; the students weren’t having it. He was forced to announce a fee freeze after four days of occupations.

Moving off campus

As the days wore on, the students, having shut down the campuses, took the fight to the streets and to the seat of political power to demand that the ANC government freeze fees and lift funding to higher education.

Government funding to universities has been declining for years, from one half of total costs in 2000 to 40 percent today. The gap has been made up by rising fees, which now account for one-third of university income, up from one-quarter.

In response to the wave of campus occupations, the higher education minister met vice chancellors and came up with a 6 percent ceiling on fee increases. Again, it was rejected out of hand by the students.

In Cape Town on 21 October, a big crowd of students marched to the National Assembly, which was then in session. At least a thousand managed to force open the gates to the parliamentary precinct and get into the grounds. They were met with teargas and stun grenades. Twenty-nine were arrested, six of whom were threatened with charges of “high treason”.

A demonstration of 1,000 was held outside the court the following day and the treason charge was dropped, but the students still face stiff penalties.

Demonstrations spread across the country the following day, as pressure grew for a national university shutdown. In protest at the violence unleashed on students outside the National Assembly, thousands of students took to the streets in Cape Town. Thousands also marched in Johannesburg to the ANC head office.

On Friday 23 October, a national mobilisation of tens of thousands made its way to the seat of government in Pretoria. Again the protesters were met with clouds of tear gas.

As they marched off their campuses, students from the University of Johannesburg and the University of the Western Cape were confronted by violent repression, including the use of water cannon, rubber bullets, stun grenades, pepper spray and, close to UWC, live ammunition as warning shots. This only inflamed their anger.

The students also had to contend with a hostile barrage from the mainstream media, which portrayed them either as violent disrupters intent on creating havoc, or self-centred and privileged. They had to combat attempts by the ANC and the opposition Democratic Alliance (the former National Party) to co-opt their movement and use it for political advantage.

The students won support from the country’s leading trade union, the National Union of Metalworkers, along with several others that have begun to break the shackles of the ruling tripartite alliance of the ANC, the Congress of South African Trade Unions and the Communist Party, which has done its best to stifle social struggle over the past two decades.

Straws in the wind

This was not just a fight about fees. It was a challenge to the entire structure and ideology of post-apartheid university education in South Africa: what it is and what it must become.

We can see a precursor to #FeesMustFall in the campaigns by low-paid workers against outsourcing of jobs. These struggles have been going for some years and have included strikes by low-paid blue collar workers, supported by student activists.

The students took up the workers’ demands as well. On several campuses, cleaning staff joined the student occupations and at Wits, campus security declared their solidarity with the students.

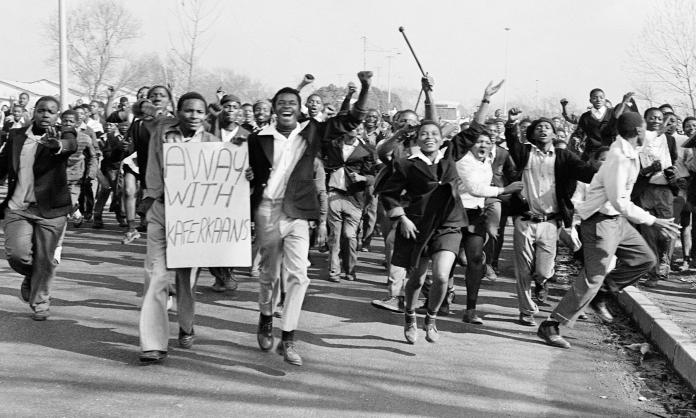

#FeesMustFall also has its roots in the longstanding demand for an overhaul of the curriculum to make it more reflective of a multicultural society, rather than one structured around white rule. Students hoisted placards making reference to “1976”, recalling the fight by earlier generations of school students in Soweto against the compulsory teaching of Afrikaans, the language of the white minority government.

Although some things have changed since 1994, the legacy of apartheid still stalks the country; anger is growing towards the ANC. As one placard put it, “Our parents were sold dreams in 1994. We are just here for the refund”.

The success of #RhodesMustFall, a campaign in March to remove the statue of Cecil Rhodes, a symbol of white supremacy across Southern Africa, from the University of Cape Town, was another factor that prepared the ground for the upheaval in October.

Frustrations have been building for a while. The announcement of double digit fee increases only brought these to the surface in a mass outpouring.

The struggle in South Africa still has a way to go, but for now the students have struck an important blow against the neoliberal agenda.

[Tom Bramble is co-editor (with Franco Barchiesi) of Rethinking the labour movement in the ‘New South Africa’ (Ashgate, Aldershot, 2003) and was a visiting academic and researcher at Wits University in 1997-99.]

* This article originally implied that students had been attacked by police within the grounds of the University of the Western Cape and the University of Johannesburg. It has since been corrected to note that the confrontations occurred after they had marched out of the university grounds.