Revolutionary Marxists argue that socialism is possible only if the working class leads a revolution. So why organise among students?

There are three key reasons. The first is that youth will always be the most dynamic, energetic and creative force in any revolutionary movement. The second is that, for centuries, students have been a volatile political layer, playing a prominent role in all revolutionary movements. And the third is that students are a mass layer in Australia and most advanced capitalist countries today, one which will almost certainly play a significant role in any future social upheavals.

So Marxists need to appreciate the strengths and weaknesses of student movements. Organising among them is imperative, but in no way implies that students can substitute for the working class as the leading element in any anti-capitalist revolution.

Socialist Alternative, the organisation behind Red Flag, has a network of clubs on university campuses as well as a number of trade union militants off campus. We are a well-known and well-established force in the national student movement, and prominent on almost all the major university campuses in the country. We argue that students are of immense strategic importance for any revolutionary organisation, and are especially critical while socialists do not have mass influence in wider society or the workers’ movement.

Because of this, it is not unusual to hear people dismiss our organisation as “dominated by students”, as if this is a bad thing. Obviously, the aim of any self-respecting revolutionary organisation is to build support and influence in the workers’ movement. But conditions are not always conducive to this, meaning revolutionaries have to be able to adapt to the conditions they are operating in in order to build support and find opportunities to put their politics into practice.

Campuses have long been important sites of political ferment and conflict in modern history, and this continues to be the case today. It was students, for instance, who sparked a workers’ uprisings against the monstrous Stalinist state of Hungary in 1956. They also played a key role in Black South Africans’ struggle against apartheid. In China in 1989, their rebellion drew hundreds of thousands of workers into the struggle for democracy.

More recently, there have been student uprisings in Chile every few years since 2011, and in Hong Kong in 2019, students led a massive confrontation with the state over many weeks, mobilising wide layers of the population in their support. One of them told Red Flag’s Ben Hillier, “It is stupid, but a lot of us feel like we are learning more from this than we do from [university] lessons”.

Unlike in nineteenth century Europe and in the twentieth century until World War II, students today are not just part of the bourgeois intelligentsia. They are a mass “declassed” layer, without a fixed and permanent position in any particular social class, which is drawn from a variety of class backgrounds and whose future social location is uncertain.

Some become part of the intelligentsia, some go on to highly paid professional and technical waged labour. Others will be no better off than their working-class parents, going into moderately and even low-paid work such as teaching or nursing. This impermanence can make them open to different political and social perspectives, and makes them less invested in the status quo.

Radical students have accordingly played an important role in the socialist movement. Even though the student movements were weak in many countries up until after World War II, there were always individuals and small groups of students who threw in their lot in with socialists.

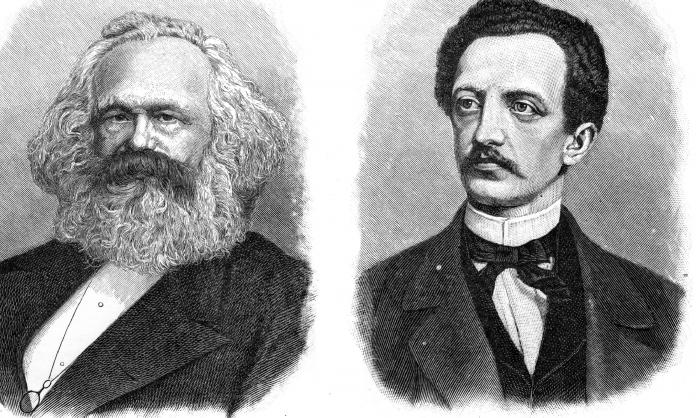

Marx and Engels developed their ideas and commitment to the working class as a result of debates that they first participated in as students. Many of the subsequent leading figures of the European socialist movement, such as Rosa Luxemburg, became socialist activists while students.

In Russia in the 1880s and 1890s, students played a key role in developing the first Marxist circles, which laid the basis to build the Bolsheviks, a workers’ party that subsequently led the 1917 revolution.

The fact that students joined the mass socialist and communist parties all around the world in the first decades of the twentieth century reflected the growing strength of the workers’ movement, which was able to pull minorities of students and other social groups behind it. Radicalising workers, in turn, were sometimes influenced by students.

In Italy, in an industrial upsurge from 1969 until 1972, student-based revolutionary organisations became quite influential and swelled their ranks with thousands of newly radicalising workers. In Australia, some of the key members of the Industrial Workers of the World and the Victorian Socialist Party early last century were students.

These are portents of the possibilities when workers move into serious struggles again. Any organisation that has not developed a layer of young members will struggle for relevance in any political radicalisation and upsurge of struggle.

Even when they are not engaged in radical struggles, it is important and possible to build among students. One reason for this is that students are more likely than workers to join a small revolutionary organisation on the basis of their ideas. They tend to deal more often with abstract theories in both social and physical sciences.

By contrast, workers tend to be more practical. They seek an organisation that can organise and lead the struggles they need, making it difficult to establish roots in the working class until there is significant radicalism among wider layers and socialists have thousands of members able to play at least some of that organising role.

The very nature of student life and their age can make them volatile, daring and inclined towards action. To organise a workplace strike, you need a majority and a determination to impose the will of that majority against scabs. This demands serious discussion and persuasion, sometimes over long periods of preparation.

On the other hand, quite small numbers of students can simply announce that a demonstration is happening, and unselfconsciously declare they are fighting for the rights of all students. Even these quite small protest campaigns can open up political discussions. Then, the ideas of different radical currents are tested, out of which some can be convinced of Marxism.

The last time there were sizeable demonstrations on Melbourne campuses, dozens of students who were not members of Socialist Alternative would regularly attend meetings on the politics of revolution after a protest of a couple of thousand. The rally numbers are smaller these days, but often similar numbers will still attend a meeting afterwards, indicating that students can be open to radical politics even when the struggles they are involved with are relatively small.

Importantly, universities are spaces where revolutionaries can organise in ways that are simply not an option in workplaces—via regular information stalls, setting up clubs for both discussions and political agitation, launching campaigns, making announcements at lectures and intervening in classes. While students work more today than previously, they still have more flexible time than most workers, so they can more easily participate in such activities.

Just wander around any university campus with its cafes and gardens and large numbers of people socialising: the different experience from that of most workplaces is striking. It is rare for workers to have time together for relaxed, informal, discussion other than fleeting interactions as they grab a coffee or during a limited lunch break. They certainly can’t spend extended amounts of time organising discussion forums and protests during work hours.

In the days after a protest, you are likely to see students from the rally around campus if you sell a socialist paper or hold a meeting; you can meet up for coffee with those who become open to discussing Marxism. This helps create a culture and sense of political community that is quite unique to university campuses.

The experience of workers’ rallies is quite different. Often you can sell lots of socialist papers and find sympathetic workers. But more often than not they have to return to work immediately afterwards. By the next day, they are dispersed across the city’s workplaces and can meet up with you only outside work hours, which creates a separation between work and politics that is not as pronounced on a campus.

There are other important considerations. If you can establish campus clubs and ongoing activity, it gives you some small social roots. On most campuses there is a milieu of political people who interact in various ways. This creates some pressure on socialist groups against simply becoming abstract propagandists. The ideas you argue are likely to be contested; you have to show their relevance and correctness. And you are somewhat accountable to people over the longer term, rather than in just fleeting political interactions that are never followed up on.

Campuses also provide an opportunity for contest and interaction with other political forces; they form a sort of microcosm of society. Student revolutionaries have to relate to Labor, Greens and independent activists, and gain experience in forming joint electoral tickets, deciding which compromises can be made within the framework of socialist principles, when to argue the point about any number of issues. And they work together to make campaigns happen, again deciding when to compromise and when to argue.

They can win student union positions that carry responsibilities not usually open to small groups of revolutionary workers in trade unions. Combined with serious study of Marxism, such regular activity can build a student cadre that can play a leading role and imbue the organisation with energy and enthusiasm. These skills are not campus specific, but provide important experience that transfers to workplaces and union activism, and can be a stimulus to greater and more effective workplace organising. It has been the experience of Socialist Alternative that a background in student activism makes for much more effective union activity than learning it from scratch once someone is already in a workplace.

A base on campuses furthermore provides a foundation from which a socialist organisation can begin to branch out. Because of their more flexible time, students can intervene when workers do move into action.

Socialist Alternative students are able to mobilise and play a constructive role in workers’ strikes, attending picket lines and garnering support for the action. In this kind of activity, they see concrete illustrations of the politics they have learnt from books and discussion groups.

Student members have shown they are capable of convincing small numbers of workers of socialist politics, of winning votes for the electoral project of Victorian Socialists in working-class suburbs. This lays the basis for a serious intervention in any sustained growth in workers’ struggles in the future.

Paul Frolich, biographer of Rosa Luxemburg, wrote of the “exuberance and romanticism” of Polish and Russian students in exile in Zurich and their fate: “Many of these young people were fated to rot away in the prisons of the Tsar or in the wastelands of Siberia. Others were destined to become props of the state as factory-owners, lawyers, doctors, teachers or journalists in some nook in Russia. Only a few were to experience as activists the revolutionary storms which they all dreamt about”. Small in number though they might have been, those few were critical.