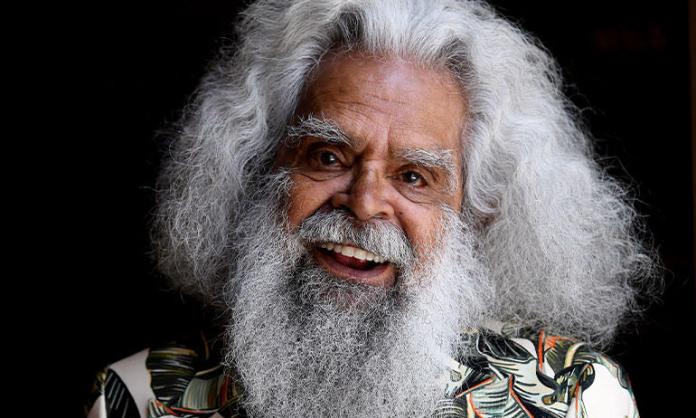

“Jack Charles is Up and Fighting” is the title of one of Uncle Jack Charles’ early shows for the Indigenous Theatre Group, Nindethana, and it sums up his life. An actor, musician, potter, activist, proud gay man, this Boon Wurrung, Dja Dja Wurrung, Woiwurrung, Palawa and Yorta Yorta elder was, as actor and director Rachel Maza put it, “a shining, vibrant celebration of life”.

His brilliance in so many fields is all the more exceptional given the brutality he faced in his early years. When he was a baby, he was stolen from his mother Blanche Charles, and did not see her again until he was 19. When he was taken and made a ward of the state, he was also given a criminal record. Later he commented, “So, my first offence ... was as an Aboriginal boy, four months old, child in need of care and attention. That was the offence”.

Several actual offences followed. He was imprisoned 22 times for burglary and drug offences as a young man. Always ready to see the political side of his life, he half-jokingly justifies the burglaries as him being a “hunter gatherer on prime Aboriginal land” who was collecting dues from those living there rent-free.

Giving testimony to Victoria’s truth-telling inquiry, Uncle Jack talked about the years in the Salvation Army Boy’s Home, where he was physically and sexually abused. “It’s hard to convey the damage that place did to me. It wasn’t just the abuse that traumatised me, the Box Hill Boys Home stripped me of my Aboriginality.”

It was only in 2021, during the making of the SBS documentary Who Do You Think You Are?, that he discovered the identity of his father and his family’s ties to more Aboriginal nations across Victoria and Tasmania. “My story has been lost, and with this story I’ve been healed again”, he said of the discovery. Over the years he found out his forebears had been part of the Blak political peoples who resisted government intervention at Coranderrk, a reserve for Aboriginal people in northern Victoria.

Acting was where he really shone. “I think I owe my life to having found theatre”, he once said. He established the first Indigenous theatre, Nindethana, with fellow activist and actor Bob Maza, in 1972. Stage, film and television were home to his performances in The Chant of Jimmy Blacksmith through to Preppers, Cleverman and Mystery Road and the documentary Bastardry.

In 2010, he gave a scorching performance in Jack Charles V the Crown with the Ilbijerri Theatre Company. From stolen generation childhood, imprisoned 22 times, he talks about his whitewashed existence, then sings tongue in cheek about how grand it was that the white man came. The play demands rights for Indigenous people and, for ex-prisoners like himself, the extinguishment of past criminal records.

He ends with a blues version of Oodgeroo Noonuccal’s poem “Son of Mine”, where she writes, “I could tell you of heartbreak, hatred blind ... But I’ll tell you instead of brave and fine”.

Only recently Uncle Jack declared he still had lots to say and fight for. Speaking to the Saturday Paper, he said ,“Old thieves like me, we cry loudest when we see injustice ... We still have a problem with unaccountable deaths—in custody, in police cells and sometimes in hospitals, especially over in the West [of Australia],”

Uncle Jack was also politicised by his experience of being a gay man. In a 2019 interview with the Star Observer, his message for younger LGBTQ Indigenous people was to be true to themselves, as he was. “But always watch your back, because we’re not in a gay world. We’re living on the fringe of society, like Indigenous people, we’re fringe dwellers. So us gay and Indigenous mob, we’re fringe dwellers twice over, and that’s what gives us great strength.”

In 2021 he was more positive saying, “I have no problems being a gay and old arty bloke, because I’ve been a gay and young arty bloke for many years and everyone’s accepted it”, not to mention how he was “tickled pink” when marriage equality was won, observing that he had “thought Australia was too much of a bastard country to get it through”.

Oppression and discrimination didn’t go away for Uncle Jack, any more than for other Indigenous or LGBT people. But he always came back fighting. In 2015, hours after being named Victorian Senior Australian of the Year, he was twice refused a taxi. He told taxi companies when it happened again in 2016, “You need a bastard like me. A deadset, ridgy-didge, beyond redemption bastard like me to take on the taxi industry, to take on the challenge”.

We will remember Uncle Jack Charles in all his many attributes, as a fighter, an inspirational leader and elder, his cheeky humour, an icon of acting and so much more. Listen to him and the equally inspiring Archie Roach singing “We won’t cry”, and lift your spirits to the sky.

Rest in power, Uncle Jack Charles.