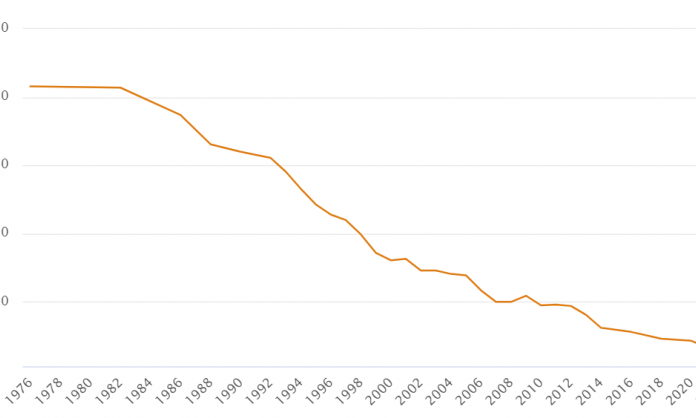

Union coverage, in steady decline since the early 1980s, took another sharp turn for the worse in 2022. The latest figures, released by the Bureau of Statistics in mid-December, show that membership has fallen by 76,000 in two years, to 1.4 million, even as the workforce has grown. The outcome is that just one in eight workers in Australia are now union members, down from one in two 40 years ago.

Declining union coverage is an international phenomenon, but the fall has been more pronounced in Australia than in most other countries. Australian unions have gone from having one of the highest rates of coverage in the West in the early 1980s to one of the lowest.

These figures do not fully convey the seriousness of the situation: just 5 percent of workers aged 20 to 24 are now in trade unions, compared to 21 percent of those aged 60-64. Unless radical action is taken, trade unions are heading for irrelevance.

What has been the ACTU’s reaction to this terrible news? Silence. Not a peep from the union peak body—nor from any other union. This is telling. That a big majority of workplaces in Australia no longer have a single trade union member is not enough to stir the union leaders into action says everything about the ruinous strategy that now dominates the upper echelons of the union movement.

If your stock in trade is to run off press releases or call upper-house politicians to lobby them about industrial legislation, you don’t need a strong union presence in the country’s factories, warehouses, hospitals, schools and offices, active union delegates and a willingness to fight the bosses.

It’s not that workers no longer have grievances or that the union leaders are unaware of them. The ACTU regularly refers to examples of workers being scandalously ripped off. It bemoans the dramatic cut in real wages that has occurred this year as prices have leapt ahead of wages. But the union leaders refuse to organise the kind of fightback needed to address these problems.

Going back to the ACTU’s Your Rights @ Work campaign to bring down the Howard Liberal government in 2005-07, the union leaders have thrown members’ resources into electioneering on behalf of the Labor Party. Time and again, union delegates have been called up en masse to phone bank for Labor, to doorknock for Labor, to hand out how-to-vote cards for Labor. The leaders tell union activists that unions will get their rights back only with Labor in office and only then will higher wages follow.

This strategy is a dead end. The Rudd Labor government that won office in 2007 off the back of the Your Rights @ Work campaign was a disaster for workers. It introduced the anti-strike laws that shackle the unions today. But the ACTU boasted that these laws were a big win. The ACTU is doing the same today with the Albanese government’s new Secure Jobs and Better Pay legislation, which tinkers with enterprise bargaining but further reduces the right of workers to strike for higher pay and better conditions. The shackles are, if anything, getting tighter with these new laws.

Why does this matter? Because the unions cannot win unless they mobilise members for a fight. This could be political, campaigning to expose the fact that the Albanese government is on the side of the bosses, not the workers. It could involve mass demonstrations protesting against the savage wage cuts now being imposed on public sector workers by Labor state governments. It could be an industrial campaign involving serious strikes to break through the public sector pay limits, or solidarity action to support groups like the West Australian nurses, who were recently left to fight alone against the McGowan government.

Political and industrial battles matter not just because they result in higher living standards, but because they infuse the unions with a fighting spirit that draws other workers towards them, establishing the basis for union renewal.

The ACTU and the rest of the union leaders don’t want any of this. They’re in bed with the ALP and look to Labor to save them. Some do it because they’ve got political careers in their sights, but most are either too lazy or too scared to mobilise their members— because it’s too much work or it risks setting in motion a struggle that might escape their control.

They want to appeal to the bosses on the basis of being “reasonable”; of being “partners” managing the business, the industry, the economy, capitalism. This is why the ACTU heaps praise on Labor’s new industrial laws on the basis that, by giving the Fair Work Commission even more power to cancel strikes, these laws might drive down Australia’s already very low strike rate.

The current membership crisis is the worst in the history of the labour movement. To turn things around, we need a complete change of course in our unions. This will involve a return to the kind of class struggle that built them in the first place.