I’m a socialist gay activist, so I’m used to being attacked for my politics. You learn to take it in your stride. But one of the most dumbfounding denunciations I ever received was issued by a few other apparently progressive queer activists, who slammed me in May 2017 for the heinous crime of speaking at a protest against the Liberal Party.

Back then, I worked full time as the national LGBTI officer for the National Union of Students (NUS). My job was to run activist campaigns that advocated for the rights of LGBTI students nationally. That same year, Malcolm Turnbull’s Liberal government announced a series of attacks on higher education funding in its May budget. Naturally, as a representative of the national student union, I spoke at the Melbourne protest against these attacks. As the day of the protest coincided with the International Day Against Homophobia, Biphobia and Transphobia (IDAHOBIT), I spoke from the platform about how neoliberalism and austerity disproportionately and acutely impact the LGBTI community. All in a day’s work for a student unionist.

Yet a week later, I was denounced by representatives from my university’s student union. At a meeting of the Monash Student Council, one elected student representative after another lined up to condemn my “shameful and disrespectful” conduct. One representative lamented that I had forced her to “choose between her queer family and her union family”. Another questioned whether I “actually cared about queer students” at all.

Why? According to the councillors, attending a protest against the Liberal government on IDAHOBIT “took away allies”, leaving queers “isolated and not engaged with the wider community”. One argued that my conduct left queer people more likely to be exposed to violent, homophobic attacks, as “allies present at events like IDAHOBIT acted as a means of protection” and on that fateful day, no straight ally was to be found. All this because I spoke against fee increases at a student demonstration—and used my platform to attack homophobia.

Within these attacks against me, basic concepts like solidarity were tossed out and replaced with a narrative of victimhood. A scan of the queer collectives and spaces in universities across Australia shows that the politics of the Monash queer reps—emphasising victimhood and looking for excuses to opt out of activism—dominates these spaces.

Yet the gay liberation movement in Australia was propelled by students who were uncompromising and unafraid to fight on all fronts. Ken Davis, who participated in the first Mardi Gras in Sydney in 1978, says that in era of ’70s youth radicalisation, “we were angry at the whole system”. Participants were motivated to fight for gay liberation, but also to take part in the movements against the Vietnam War, for environmental protection and for Aboriginal land rights.

Marxism was influential on campuses. Anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist politics infused the burgeoning movement for gay rights. Monash, where queer representatives denounced me merely for speaking against Liberals’ attacks on public services, was a pioneer for socialist gay activism. In 1976 the “Manifesto of the Socialist Homosexuals” was published in a special edition of Monash student newspaper Lot’s Wife. It explicitly condemned “attempts of the capitalist Liberal-National Country Party Government to lower the living standards of the working class through wage freezes and ‘social contracts’”. The manifesto attempted to use Marxism—in particular the work of Friedrich Engels on women’s oppression and the nuclear family—to connect gay oppression to the oppression of women and to class exploitation. It would have been a no-brainer that gay activists would organise against Liberal Party attacks on the working class and the poor.

Locating gay oppression in the nuclear family—a bedrock of capitalism—meant the anti-capitalist authors of the “Manifesto” saw that their oppression linked up not only with that of women but also the working class and other social layers oppressed by capitalism. “Here and now in the struggle against exploitation and oppression, solidarity with each other’s struggles provides the basis for tomorrow’s unity on the barricades”, they wrote. The gay movement benefited immensely from seeing itself, not as an isolated struggle, but one that could strengthen and be strengthened by other radical struggles.

Gay student activists influenced by Marxism looked to the working class as an important ally. In 1973, Jeremy Fisher, a student at Macquarie University, was kicked out of his residential college for being gay. Fisher went to the Macquarie University Student Council, which in turn took the issue to the construction workers on campus, organised within the militant Builders Labourers Federation. After some debate, the BLF unanimously voted to down tools and refuse to continue any work on campus until Fisher was reinstated.

The first Mardi Gras was a protest against the “pink dollar” that now reigns supreme at that event. According to Davis, what began as a nighttime march of about 500 protesters drew people out of the gay bars along Oxford Street and into direct confrontation with the police The bars were run by organised crime. The police saw this march as a threat to the relations between criminal gangs and the police. When activists marched down Oxford Street, police responded with violence and arrests. Police brutality only invited more militancy: the next night, there was another demonstration outside the police station were activists were being held. Activists from around the country descended on Sydney to take part in rallies, meetings and assemblies to coordinate a response. There were debates about the way forward, but a common commitment to radicalism and militant action prevailed.

But the next decade was marked by a shift to the right in society. The elections of both Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan were followed by efforts to roll back the gains of the ’60s and ’70s. The dawn of neoliberalism meant a retreat on university campuses from the revolutionary ideas of Marxism to the faddish ideas of post-Marxism and postmodernism. The AIDS epidemic laid waste to gay communities across the world, with tens of thousands of gay men cut down while governments and health bureaucrats were unable or unwilling to help. That was met with resistance: the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) was one such organisation that resorted to direct action tactics to highlight the plight of LGBTI people dying as a result of government inaction. But gay politics could not resist society’s overall shift to the right.

In the ’90s, a new kind of politics emerged associated with the concept of “queerness”. In the United States, groups like Queer Nation formed, based on a sort of counter-cultural identity politics. Early adherents of this queer politics engaged in some militant direct direct action, but they took their theoretical cues from Michel Foucault and Judith Butler, not the socialist movement.

These queer activists saw gender and sexuality as socially constructed categories and were critical of the coopting of a minority of LGBTI people within the state and corporations. But, with no coherent class-struggle strategy in their politics, many have become senior queer bureaucrats and bosses themselves. Queer academic Annamarie Jagose writes that “queer describes those gestures or analytical models which dramatise incoherencies in the allegedly stable relations between chromosomal sex, gender and sexual desire”; she’s now the course-cutting dean of arts at the University of Sydney.

Queer theory presented itself as anti-system and critical of capitalist “heteronormativity”, but it was hostile to Marxism as a “totalising” system of thought. Queer theory observed how artificially gender and sexuality were constructed, but it emphasised performance and the allegedly radical potential of “queer” identity. It counterposed lifestyle changes to solidarity, mass struggle and total human liberation.

From 1999, a new student movement in Australia was born influenced by the anti-corporate movement taking place across the world. Events like the 1999 Seattle protests against the World Trade Organization and the 2001 Genoa protests against the G8 summit created a sudden radicalisation in Australian students. LGBTI students played a notable role as the queer collectives radicalised. Theirs was an anti-capitalist politics influenced by a number of different strains: Marxism, anarchism, feminism and, of course, queer theory. Mark Pendleton, the NUS queer officer in 2001, describes the politics of queer student activists at the time: “The new anti-capitalist queer groups base their action on an explicitly anti-capitalist and implicitly Marxist analysis of queer oppression. Their core belief is that homophobia is perpetuated by the economic system of capitalism. That being said, there are certainly remnants of an identity politics within the anti-capitalist queer movements”.

Queer blocs participated in demonstrations such as the 2000 Melbourne protest against the World Economic Forum. Campus-based groups like Queers United to Eradicate Economic Rationalism (QUEER) formed. In Sydney, a similar group called Gays and Lesbians Against Multinationals (GLAM) formed, later to become Community Action Against Homophobia (CAAH), a group that was key in organising protest action for marriage equality years later.

But the influence of queer theory kept creating problems. In targeting the mainstreaming of gay identity, queer student activists often rejected reforms, such as marriage equality, on the grounds that they “privileged” monogamous relationships that conformed to mainstream standards, undermining alternative relationship structures like polyamory. But fighting for legal equality helps build mass movements in solidarity that can go on to win further gains; abstaining intensifies the division and separation of oppressed groups. While queer theory was against essentialist explanations of gender and sexuality, its adherents often upheld so-called lifestyle politics and ultimately retreated to demanding “safe spaces” for queer students.

“Safe spaces”, despite representing a retreat from struggle and public life, once encountered hostility from state and university administrations. In 2004, the University of Wollongong queer collective Allsorts occupied their queer space when the university kicked the collective out of the space in order to build a new bar. Fast forward to today, and the picture at Wollongong is quite different. Allsorts still exists but without a modicum of that militancy. A witness to the collective’s 2017 “Wear It Purple” picnic—an initiative aiming to increase visibility of young LGBTI people by wearing purple clothing—reported that the Allsorts collective had invited the local police also to “wear it purple”. Whereas in 2004 police dragged queer activists from their space, in 2017 purple-clad riot police picnicked with the collective on the lawn.

National queer student conferences like Queer Collaborations have descended into poorly attended social gatherings, featuring “workshops” on foot (and sock) fetishes, autonomous meetings for a seemingly endless array of sub-identities such as asexuals/aromantics and people in polyamorous relationships. These conferences, like queer spaces on campus, are totally devoid of any attitude towards collective organising.

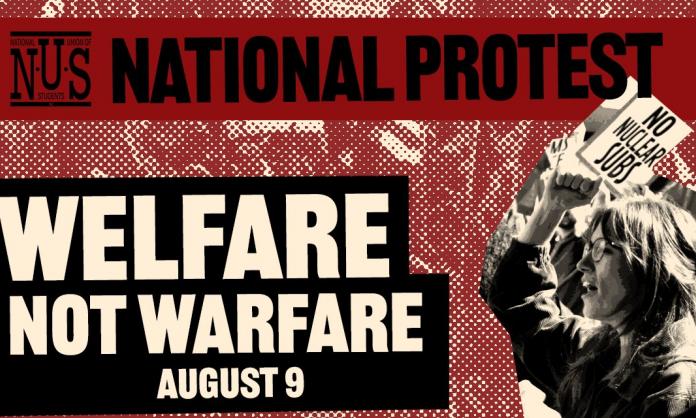

This mirrors the poverty of politics within student organisations more broadly. As recently as 2014, student unions were able to launch and coordinate national campaigns against neoliberal attacks on higher education, as well as social campaigns against war and militarism, for refugee rights and others. Yet today, student unions around the country, under the direction of members of the Labor Party, have turned fighting unions into service provision bodies better at organising a barbecue than a speak-out for student rights.

It doesn’t have to be like this: when socialists have been able to take a lead, positive things have happened. Despite being criticised by student politicians throughout 2017, I was able to help coordinate student participation in the successful campaign for marriage equality. This built on the work of previous socialist LGBTI students, who had collectively spent 13 years fighting for this basic right. Socialist LGBTI students in recent years have led campaigns against gay conversion therapy, for the rights of trans and non-binary students to use the bathrooms of their choice and, most recently, against a bill in NSW that would prevent teachers and school staff from teaching pupils about trans issues, among other contemptible measures.

Australia has a rich history of radical LGBTI students leading struggles for their own liberation, emphasising collective action and Marxist theory that empowers people to care not only about their own struggle but also the struggles of others. Rebutting the myopic focus solely on queer issues and on moderation, Davis argues that the “problems faced by queer employees aren’t solved when their company puts on rainbow flags or whatever the fuck they are doing. Instead of demanding symbolism, we’ve got to look at the big issues, like labour rights, migration, housing, health care, or who runs schools or welfare. Those are the key issues for queers—not whether your boss is openly homosexual”.