In January 1973 the New South Wales town of Wee Waa was shaken by a strike of more than 1,000 cotton chippers. Most of the workers were Aboriginal, and the strike challenged the racism and exploitation that were deeply entrenched in what was the central industry of the region.

Large-scale cotton farming was introduced into the area in 1961. Angela Keys’ unpublished thesis Industrialised Cotton Production: From California to Australia’s Namoi Valley explores how American cotton industrialists played a key role in establishing the industry in Wee Waa, and shows that they modelled their farms on the Jim Crow system in the US South. A report by the Australian in 1966 described the mentality of the American cotton growers in rural NSW—explaining that “the Negro stalks the edges of their conversations”—and argued that many had moved to Australia to escape the intensifying civil rights struggle in the US. According to a March 1966 article in Tribune, the newspaper of the Communist Party, Wee Waa had become sarcastically dubbed “Little America” by locals.

The conditions were horrendous. The work was seasonal, so from December to February around 1,000 mostly Aboriginal workers and their families would travel to Wee Waa from across NSW to work the cotton. Cotton chipping involves a gang of workers walking up and down the rows, “chipping” out weeds with a hoe. The anti-racist activist Bobbi Sykes, writing in the Nation Review on 19 Jan 1973, explained that the 90 percent Aboriginal workforce toiled for ten hours a day for $1.12 or less an hour, child labour was widespread and “smoko” breaks were banned. Of the “many Americanisms” that were imported into the cotton fields, Sykes reported that the one which angered the workers the most was “the use of binoculars by patrollers to watch that workers are not resting for a few minutes”.

Sykes also explained that sanitation was confined to water from the same river that was used for the cotton, leading to outbreaks of kidney disease that particularly affected the children of the cotton chippers. The bosses provided no accommodation for the Aboriginal workers, who had to build their own temporary camps or simply slept in their trucks or outdoors for three months. Crop dusting planes sprayed the workers and their families with poisonous insecticides that also drained into the water supply, leading to further health problems.

In March 1966 Tribune reported that a cotton picker named William Morgan lost his eyebrows and some of his hair when a plane dumped some of its pesticide on him. The local hospital was segregated, with Aboriginal people confined to the verandah. In the lead-up to the 1973 strike, Reverend H. Herbert’s report for the Australian Council of Churches detailed that ten cotton chippers had died from these gruelling conditions, including a 17-year-old boy.

Each year, when the chipping season ended, the bosses and the local council would drive the cotton chippers out of town, police and government officials breaking apart the temporary homes and arresting anyone found “loitering”. Police harassment was constant. In 1972 Tribune reported that eight Wee Waa police officers managed to arrest more than 200 Aboriginal workers during patrols on New Year’s Eve at the cotton chippers’ camp.

At the end of 1972, the Wee Waa Aboriginal Cotton Chippers Caucus was set up. It was founded by a mix of younger Aboriginal workers who had spent some time involved in activism in Sydney, such as Lyall Munro Jr, and prominent local Aboriginal activists such as Arthur Murray. Arthur had been fighting for better conditions for the cotton workers and their families since he moved to the town in 1969 and had previously set up a committee called the Aboriginal Advancement Association, which protested to the local council for better housing and medical treatment, to little effect.

Establishing the caucus was necessary because the Australian Workers’ Union (AWU), which was supposed to represent the interests of the cotton chippers, had totally failed to do so. Sykes reported in the Nation Review that representatives of the cotton workers spoke at a press conference in January 1973 “of black disillusionment from years of apathy and double talk from the AWU”. The Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) was also condemned for its lack of action over the issue. As Sykes explained, despite then ACTU leader Bob Hawke claiming to support the workers, he refused to do anything about it unless the AWU asked the ACTU to intervene.

Neither was there any action from the newly elected Labor government of Gough Whitlam. It was expected, according to Sykes, that with the election of Whitlam in 1972, the cotton workers’ “efforts should not only be supported, but that conditions such as exist at Wee Waa [would] be completely exposed and eradicated”. These hopes were dashed, and in order to fight for their rights, the cotton chippers had to organise independently of both the official structures of the AWU and the Labor Party.

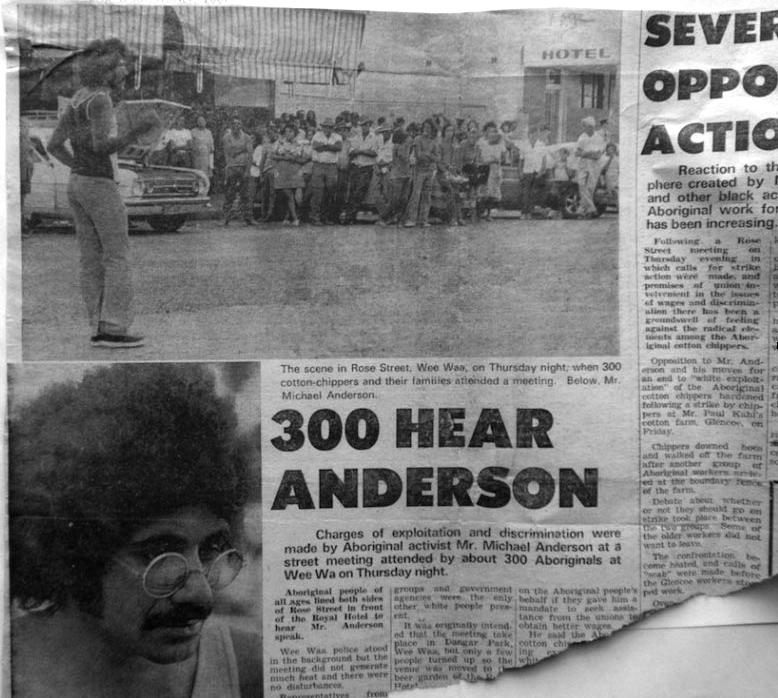

In an interview with the Griffith Review in 2019, Lyall Munro Jr explained that the caucus started meeting at the back of the Royal Hotel, and organised a series of protest meetings in the first days of January 1973. These meetings rapidly grew to include hundreds of workers and attracted harassment from the police. Preparations started to be made for a strike, and the caucus was renamed the Cotton Chippers’ Union.

On 6 January, 47 Aboriginal cotton chippers were arrested after one of the protest meetings, and tensions in the town grew. Then on 9 January, 300 cotton workers protested outside the Imperial Hotel, which denied service to most Aboriginal people in the town. According to a report in the North Western Courier, the publican locked the doors to the hotel and refused to speak to the protesters.

This was followed by a march of 500 two days later and then a 24-hour strike at the Glencoe farm owned by Paul Kahl, who had been one of the first Americans to grow cotton in Wee Waa. An indefinite strike began on 22 January. The Northern Daily Leader reported the next day that the strike had widespread support, with only 60 refusing to join it out of a workforce of around 1,500. This, crucially, was right in the middle of the chipping season.

The bosses and their supporters went berserk. The 25 January editorial in the Wee Waa Echo—titled “The Communist Strategy”—argued that “what is happening in Wee Waa at present is indicative of the kind of strife which radicals and professional trouble-makers can make”, adding “it is not fanciful to see the Aboriginal problem as the powder keg for Communist aggression in Australia”. Tribune reported that white vigilantes, rumoured to be employees of the cotton bosses, attacked the cotton chippers camps in the dead of the night and burnt down their tents. In 2012, Michael Anderson recalled, in a statement on the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization website, that one night during the strike he was told his life was in danger and he went to stay with family in town. After he had fled, “two shot gun blasts were fired into the tent and the people said a white 4WD had sped off into the darkness”.

But as the strike took off, it attracted not just enemies but also allies.

The chippers’ strike took place at a high point in both working-class activism and radicalism over the issue of Aboriginal rights. In Redfern in Sydney, Fitzroy in Melbourne and South Brisbane, a new generation of young Indigenous activists, influenced by the politicisation of African-Americans in the US and struggles against racism in Australia, had embraced the politics of Black Power. They become notorious for their militancy and radicalism. Many of the activists involved in the chippers’ strike had connections to the Black Power movement.

Anderson and another activist, Billy Craigie, had already arrived in Wee Waa before the strike as representatives from the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in Canberra. Anderson, whose family were from the Wee Waa region, stayed in the area throughout the campaign of the cotton chippers and became the spokesperson for the workers. As the campaign took off the Aboriginal Legal Service in Redfern—which had been set up by Black Power activists—sent Paul Coe and Sol Bellear to provide legal support for the arrested strikers.

The Black Power activists also brought with them connections with non-Aboriginal workers in the left wing of the trade union movement in Sydney. This was a time of large-scale industrial action by workers and a radicalisation around a whole series of political issues. In the ’60s and early ’70s, there had already been working class support for the Gurindji strike in the Northern Territory, and socialists in unions like the Builders Labourers Federation had worked with Black Power activists in Redfern in a range of campaigns.

Lyall Munro Jr recalls Michael Anderson organising cotton workers like him to be toured around construction sites in Sydney by builders’ labourers in order to raise money for the strike fund, and communist trade unionists arranged for some of the strikers to speak to a meeting of the Trades and Labour Council, which then endorsed their struggle. Tribune reported in January 1973 that $1,400 was raised for the strike fund, including $295 from building workers on the Opera House revolving stage. Unsurprisingly, the conservative AWU refused to contribute to the strike fund. The cotton workers would remember this for some time to come. After the strike was over, the AWU arrived in Wee Waa on an organising drive and was sharply rebuffed by the majority of the cotton workers.

This coming together of non-Aboriginal trade unionists and Black Power activists in the cities with rural working-class Aboriginal people was an important step in breaking down the racism in country NSW. It also showed that moderate critics who portrayed the Black Power activists in Redfern as an urbanised elite who alienated the majority of poor Aboriginal people with their militant tactics and ideas, couldn’t have been more wrong. The struggle of the cotton chippers was an opportunity to show that the Aboriginal radicals in the cities could connect their struggle against racism with the interests of rural Aboriginal workers and win support for that fight from working-class whites.

Six days into the indefinite strike, the cotton bosses met with the leaders of the Cotton Chippers’ Union and agreed to raise the hourly pay rate to $1.45 and introduce double-time for Saturday and Sunday work. While issues such as housing and sanitation remained unresolved, this was still a big victory. The cotton bosses had been forced not only to negotiate with an unofficial breakaway from the AWU but also to concede to some of their demands.

The 1973 strike would be remembered for years to come, and not just by the cotton workers. Arthur Murray, who had emerged as one of the strike leaders, would suffer from police persecution for the rest of his life. The police never forgave Murray for his role in the strike nor his continued activism for the local Aboriginal community.

Peter Gray’s radical history of Wee Waa, published on radicaltimes.info, details the harassment of the Murray family. One night the police arrived at Arthur’s house and told him to get his daughter out of the police van. According to Gray she was “covered in blood”.

In June 1981 Arthur’s son Eddie came home to visit the family. While drinking at the Imperial Hotel, he was arrested for being “drunk and disorderly”. Witnesses say that when the police arrived they started chanting “Come on Eddie Murray, we want you, come on Eddie Murray, we want you”. Later that night Eddie was found dead in his cell, with the police claiming he committed suicide. The campaign around this injustice was one of the major factors that eventually led to the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody.

Despite the vile harassment of the Murrays, the 1973 cotton chippers’ strike helped inspire a whole generation of working-class Indigenous activists. Decades later Lyall Munro Jr explained in his interview with the Griffith Review that the strike was his first “foray into politics”. It was at the protest meetings of the cotton workers that Munro Jr first spoke before a political audience and the first time he got arrested. “The rest they say is history. It became a new part of my life. A demanding part of my life, and it was a time of an awareness that I suppose ‘got our goolie up’ as they say, the resistance went from there.”