Between 2005 and 2012 Australia underwent the most dramatic mining boom since the Victorian gold rush. Investment in the sector, broadly defined, quadrupled. The boom also fuelled growth in a wide range of industries servicing the sector, in particular engineering construction and business services. And when coal and iron ore came off the boil, construction of LNG projects helped to take up some of the slack.

We are now living through the post-boom hangover. Three factors have come together to deliver a blow to economic growth and national income. The first was widely predicted – the end of the mining investment boom as the construction of mines and related infrastructure is progressively completed. As investment is wound back, jobs in the industry have fallen. Economies that rose off the back of the mining boom, WA, SA and Queensland, are now undergoing the burden of adjustment.

Rather less widely predicted have been two other factors – a big rush of new supply of minerals in world markets, with BHP Billiton, Rio Tinto, Fortescue Metals and Brazil’s Vale all flooding the world with record shipments of iron ore, alongside a rapid slowdown in the rate of Chinese economic growth and demand for commodities.

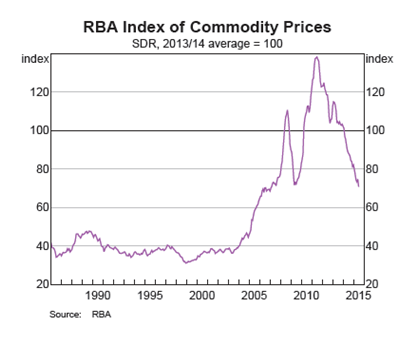

The effect of these developments has been a collapse in commodity prices (Figure 1), with further falls predicted. Australia’s terms of trade, the ratio of export prices to import prices, have fallen back after rising strongly during the mining boom. The slowdown in China will have a big impact: the IMF estimates that it could knock a full percentage point off Australia’s annual growth over the next five years.

SOURCE: RBA, The Australian economy and financial markets chart pack, September 2015

As the mining bubble has deflated, however, the property sector has undergone something of a mini-boom, with prices rising in Sydney by 49 percent and in Melbourne by 21 percent since 2012. Investors have driven the boom, especially in Sydney where they account for nearly half of all new housing loans. First home buyers, by contrast, are now responsible for only one in seven new housing loans.

Property developers have jumped in to take advantage of higher prices. Between 2011 and 2015, monthly housing approvals rose from 11,500 to 19,000 a month, with apartments leading the surge. Foreign investment has become an important factor in the construction of new inner city apartments in Sydney and Melbourne in anticipation of continuing strong immigration and high enrolments of international students. The revival of building construction has also helped to push up employment in the construction industry, more than sufficient to compensate for the loss of jobs in mining.

The property boom has stimulated spending on furniture, floor coverings, housewares, hardware, building and garden supplies and electrical goods for the new units and houses. It has also fuelled increased spending on renovations, both by homeowners looking to sell and investors wanting to flip their properties. While most of the whitegoods, tiles and other fittings are imported, the labour involved and the retail trade generated have helped to boost the domestic economy.

Australia’s big four banks have done well from the property boom. Loans for housing account for 60 percent of their lending book, up from 50 percent in 2008. Their profits surged to $29 billion in 2014 and their share prices more than doubled in just three years, far outstripping the market index. The housing boom has also been a boon to state governments in NSW and Victoria as stamp duty receipts have risen sharply.

Rising property prices have had a broader stimulatory effect on the economy via the ‘wealth effect’ – the total value of dwelling stock in Australia has risen by 30 percent since mid-2012. Retail turnover has been rising at an annual rate of 5 percent in 2014-15. Bankruptcies, both personal and business, have fallen steadily over the past four years, helped by record low interest rates. Job advertisements rose for the two years to June 2015.

The mining investment boom and, more recently, the property and financial lending boom helped Australia avoid recession in the aftermath of the global financial crisis when growth in other advanced economies was slow or non-existent. After some delay, this eventually fed into the stock market with the ASX200 rising from 4,000 in June 2012 to just shy of 6,000 in February this year.

Current problems

There are, however, several problems currently besetting the Australian economy, with the September slide in the stock market only a symptom of wider issues

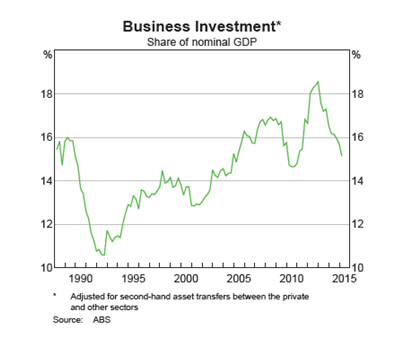

The first problem is that the uptick in construction investment in the property sector has not been enough to offset the combined effect of contraction in mining-related engineering investment and the longer and more gradual dropping-off of investment in machinery and equipment. The result is that business investment has fallen for three straight years (Figure 2). Low interest rates may have contributed to the housing boom but have had little effect elsewhere: in many cases, company boards have opted to pay out higher dividends to shareholders rather than plough their accumulated surpluses back into expanding the means of production.

SOURCE: RBA, The Australian economy and financial markets chart pack, September 2015

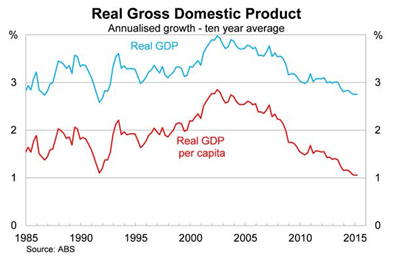

The downturn in investment is hurting economic growth. The announcement of a feeble second quarter growth of just 0.2 percent this year (and 2.0 per cent annual growth) only confirmed what has been obvious for a while now: the growth engine in Australia is sputtering. Indeed, looked at over the long term, growth has been trending down for many years, and when population growth is controlled for, the situation looks worse again (Figure 3). Successive governments have been using trend growth rates of 3.25 percent for their budget projections; the Commonwealth Bank and IMF have now suggested that 2.75 percent is more likely and even this looks overly optimistic – growth since the GFC has averaged only 2.5 percent per annum.

SOURCE: Callam Pickering, 2 September 2015

The slowing down of economic growth is due in part to Australia’s productivity shortfall. Total factor productivity has been growing much more slowly in the past decade than in the 1990s and early 2000s. While some of this is due to the mining sector, where huge capital investments were not met by an equal expansion of output, and in agriculture suffering from drought, the slowdown in productivity was broad-based.

If GDP is still growing, albeit more slowly, Australia’s income has been falling – an ‘income recession’. Net national disposable per capita income, which adjusts for the falling terms of trade, net income flows (into and out of Australia) and population growth, has been falling since 2012.

Lower growth means lower growth in tax receipts – tax as a percentage of GDP is consistently falling behind the optimistic projections in Budget papers. Low growth also pushes up unemployment which is currently at a 12-year high. Australia is the only OECD member state where the unemployment rate has been rising over the past three years. High unemployment raises the ratio of spending to GDP because of increased outlays on social security.

Slow growth of tax revenue and more social security spending puts more pressure on the budget deficit. Projections made in 2014 by Treasurer Joe Hockey for a return to surplus in 2019 are even more unrealistic now than when first announced.

Higher unemployment weakens net migration – it deters potential immigrants and discourages Australians overseas from returning. New Zealanders for example are going home in larger numbers and far fewer are packing up to settle in Australia. Lower net migration also has a big impact on population growth given the country’s dependence on immigration. While lower population growth reduces outlays on social spending, it also slows the rate of growth of consumer spending and puts downward pressure on the housing market. And, because migrants tend to be younger than the population at large, a fall in net migration reduces the economically active sector of the population.

Vulnerabilities of the Australian economy

Other problems loom in the coming period. While the property boom has helped to ease the transition from the mining boom, it has its limits. First, it is restricted to just two cities: most other capitals have seen only very modest price growth. Second, there is now significant oversupply in inner city apartments, in Melbourne in particular, and more and more investors are selling at a loss. The fact that many investors are buying their properties off the plan on interest-only loans is a further point of weakness: in a rising market, investors can prosper, but in circumstances of over-supply and difficulties in finding tenants, the outcome can be a serious financial loss.

There is a longer-term problem with the property market. Dwelling prices have risen from three times average annual incomes in 1991 to five times income today (and nine times income in Sydney). This is the product of easy lending practices by banks since financial deregulation, tax incentives for investors, low interest rates and, in some jurisdictions, supply bottlenecks. Higher house prices have been the biggest contributor to the rise of household debt relative to income, from 50 percent in 1991 to 156 percent today.

Even though clearance rates at auctions for freestanding houses in Sydney and Melbourne are still healthy, high levels of personal debt, combined with sluggish wage growth, the highest unemployment rate for 12 years, and now Reserve Bank pressure on the banks to limit their loans to investors, all set limits on how long the property sector can keep booming. The IMF estimates that housing prices in Australia may be anything from 4 to 19 percent overvalued, with Sydney a particular area of concern.

The vulnerability of the banks to problems in the housing sector can be exaggerated. We are not facing the same situation as US banks in the run-up to the sub-prime crisis in 2007. Low-doc loans, never as significant as in the US, have virtually vanished from the Australian housing market, non-performing loans are low, and the loan to value ratios for both owner occupiers and investors are relatively stable. Few households have debts larger than assets.

Nonetheless, the banks will not be immune to any serious deterioration in the housing market if it eventuates. The IMF predicts that a significant fall in house prices in Australia in the context of international financial volatility will not break the banks but will do serious damage. Foreign funding now represents 27 percent of total Australian bank liabilities and disruption overseas will hit hard in Australia as international lenders pull money out of the country. A housing bust will also have broader macroeconomic effects as the wealth effect turns negative and investment and employment in housing construction wind back.

A second long-term problem facing Australian capitalism is that it is structurally quite unbalanced. In relation to international trade, Australia remains very dependent on selling a narrow range of goods – iron ore, coal and coke, natural gas and gold are four of the top five exports and constitute 44 percent of total exports of goods and services. Including rural goods takes the figure to 56 percent. In all five areas, Australian producers are price-takers on world markets. Only international education and tourism challenge the domination of primary products. As a commodity and farm products exporter, Australia is in direct competition with the “emerging market economies” – Brazil, Russia, Indonesia, along with Canada and South Africa.

For a period during the late 1980s and 1990s, elaborately transformed manufactures – car components, aircraft parts and so forth– were a growing element of Australia’s exports, but this has now ceased. Manufacturing appears to be in a continuing downward spiral, crippled by the high dollar for several years, a small domestic market, low investment in R&D and relocation to low cost countries. The closures in the automotive and steel industries symbolise the decline in the manufacturing sector, exacerbating regional difficulties in South Australia and NSW.

Exposure to international troubles

The Australian capitalist class is trying to undertake a major structural shift in the economy away from reliance on investment in the resource sector at a time when developments in the international economy have turned sour.

For several years the international environment has been relatively benign for Australian capitalism, with China booming and the US recovering from the GFC.

The stabilisation in the world economy after the GFC was underpinned by a big program of printing money by the Federal Reserve Bank, known as quantitative easing (QE). QE involved the Fed buying corporate and government bonds from banks, flooding the world with US dollars. This forced interest rates down: for more than six years the Fed has run an interest rate of just 0.25 percent, unprecedented in US history. With cheap money, and plenty of it, investors poured their money into the US stock market, pushing up the Dow Jones industrials index by 130 percent from February 2009 to its peak in May 2015. Other central banks eventually joined in with their own QE programs, and asset prices around the world moved up. All told, central banks have injected $10 trillion in funds over the last five years, an enormous program of monetary easing.

Today, the whole process has gone into reverse. Stock markets are down across the board since the northern Spring, and there is growing concern about a global slowdown in the world economy.

The decline in international stock markets is the result of several factors. The first is the retreat in China. Following the introduction of a huge stimulus package in 2009, which included the rapid expansion of credit and immense rates of fixed investment in housing, manufacturing and infrastructure, the Chinese economy grew by 12 percent in 2010. Growth is now down, officially, to 7 percent and some economists estimate it to have fallen as low as 5 percent. Extremely high rates of investment have resulted in endemic overproduction and excess capacity in a wide range of basic industries, including steel, aluminium, cement, coal, solar panels and shipbuilding. This has cut into profits and encouraged Chinese producers to offload surplus capacity onto world markets at below cost. Bubbles in the property markets and share markets have now bust, adding to the problems.

With China now the world’s largest trading nation, its economic slowdown is having a major effect internationally. Lower prices and lower demand for commodities by China are pushing down the currencies of the big exporters – Brazil, South Africa, Russia, Indonesia, Malaysia, New Zealand, Canada and Norway, as well as Australia. While these countries grew on the back of rising commodity prices, they are now suffering from the bust, and foreign investors are rapidly pulling their money out. The same is true with Turkey and Thailand.

In order to prevent their currencies from collapsing, central banks in the affected countries are selling their foreign exchange reserves which are typically held in US and European bonds. In August alone, China spent $94 billion trying to halt a rapid slide in the yuan, while central banks in other emerging market economies spent $70 billion to put a floor under their currencies. Sales of US and European bonds by the central banks of the commodity producers have swamped the effect of bond purchases by the central banks of the US, EU and Japan – quantitative tightening is now outrunning quantitative easing, putting upward pressure on interest rates and downward pressure on the stock markets.

There is no sign that capital outflow from the emerging market economies is going to end soon, ensuring that monetary tightening –with its contractionary effect on the world economy - is going to continue. The emerging market economies – hailed in recent years as the saviours of the world economy in a period of slow growth elsewhere - are now dragging it backwards.

Slowing Chinese growth is hurting not just the commodity exporters. The slowdown in Chinese manufacturing is weakening demand for machine tools, and thus the export trade of Germany, the US and Japan. It is reducing demand for components produced in China’s Asian neighbours which are now heavily integrated into regional supply chains with China the point of final assembly. Slower income growth in China, along with a crackdown on corruption, is cutting sales growth of Western luxury cars and prestige fashion and consumer brands on Chinese markets.

China’s economic slowdown is the most immediate cause of the stock market turmoil around the world. The second is the weakening of what has only been a shallow recovery in the mature capitalist economies following the GFC. The US recovery, held up as a sign of hope, was the weakest since 1945 and the 4 percent growth recorded in the first half of 2015 is expected to slow to 2 percent in the second. Britain, another supposed success story, is not faring any better, while much of the EU is stagnant or growing at barely 1 percent. In Japan, Abenomics has failed to lift growth beyond its trend rate of just 0.5 percent and the economy is now entering its second recession in two years. The advanced economies have not broken out of what Michael Roberts calls a ‘long depression’, and across the world economy, growth and trade remain feeble.

The third factor casting a pall over world stock markets is the strengthening of the US dollar. Banks and other financial institutions which have pulled their money out of the emerging market economies are investing in US dollar denominated assets, which are regarded as a safe haven during financial volatility. Funds are also being pulled to the US in anticipation of a lift in interest rates by the Federal Reserve.

A strong greenback, however, raises the interest repayments of businesses around the world which took out large loans denominated in US dollars, taking advantage of a prolonged period of low US interest rates. Many of these companies, however, earn their revenues in their own national currencies which are now falling sharply against the US dollar. Both their outstanding debt and their repayments are rising: they have to run faster just to stand still. The same applies to companies which engaged in the “carry trade”, borrowing from the US at interest rates of 1 or 2 percent to invest in securities overseas yielding 4 or 5 percent. A sure-fire money earner for some years while currency markets were relatively stable, this strategy is now burning money. Both processes raise the prospect of a corporate debt crisis.

As for companies based in countries which peg their currency to the US dollar, they are also not escaping the effects of the dollar appreciation and drop in the yuan. The lower yuan (along with dumping of excess capacity) is giving Chinese companies a competitive edge on world markets, forcing down prevailing prices and thus profits for those of their competitors whose currencies are linked to the dollar.

A strong dollar also has a damaging effect on those US companies – many of them America’s largest and most successful - which generate a significant share of their earnings on overseas sales or from operations overseas. Take Apple, for example. With the dollar strong and yuan weaker, profits repatriated by the company on its sales of iPhones in China are now worth less.

In summary, the world economy, driven by the slowdown in China, appears to be headed for a deflationary cycle of falling prices of commodities and finished goods, falling sales, falling stock markets and declining world trade, all of which will serve to discourage investment.

The much-vaunted global economic recovery since the GFC therefore appears to be built on sand. There has been a recovery in asset prices but not in investment in productive sectors, the only sure basis to produce new value in the capitalist economies.

The only real boom has been in fictitious capital. The banks were saved by QE but the real economies of North America, Western Europe and Japan have not been restored to good health. But the fictitious capital that accumulated during the post-crash financial bubble is now being liquidated as deleveraging kicks in. The wealth effect accompanying the stock market recovery in 2010-15 will now go into reverse.

The nervous state of the financial markets underpins the Federal Reserve’s caution about raising interest rates by even just one quarter of a percent. Federal Reserve chair Janet Yellen has held back from doing so for fear that higher US interest rates will trigger a wider sell-off in stock markets and destroy any buoyancy in the real economy in the US and overseas at a time when deflation is a real threat. Persistent low US interest rates have both been the fuel for asset price inflation but also an indication of the weakness in the global economy.

Offsetting factors

The international situation is only contributing to concerns about the Australian economy – the IMF estimates that Australia will be the hardest hit of all the OECD member states by the Chinese slowdown.

Nonetheless, despite the headwinds facing the Australian economy, their impact is lessened by an important offsetting factor - the rapid devaluation of the Australian dollar from a peak of USD1.10 in 2011 to USD0.70 today, along with smaller but still significant falls against the currencies of other major trading partners.

The lower dollar creates a buffer for the Australian economy. First, it partially offsets the decline in commodity prices which are set in US dollars – if commodity prices decline by 10 percent, a 10 percent decline in the value of the Australian dollar against the US dollar will ensure Australian dollar earnings remain the same, putting a floor under the income of the resource exporters. A lower dollar also benefits rural exporters, boosting farm incomes.

The depreciation of the dollar also benefits three industries which were hard hit for several years by the strong dollar: tourism, now seeing a surge in Chinese tourists and more Australians holidaying at home; international education, which dipped in 2009-2012 but is now recovering as Australian university fees become more competitive; and some sectors of retail, as overseas online shopping becomes more expensive. The downside, of course, is that a lower dollar will make a range of imported raw materials and intermediate and capital goods more expensive, raising costs of production.

The lower dollar will potentially allow capitalists operating in Australia to benefit more from the new free trade agreements recently signed with Japan, Korea and China. These agreements offer business opportunities to the resources sector, agribusiness, as Australia pitches itself as a provider of safe food for East Asia, and personal and professional services like healthcare and wealth management.

The Australian government will also benefit from the big boost to LNG exports coming on stream in coming years, although manipulation of tax affairs by the multinational LNG companies (‘profit shifting’) may limit the benefits from this development.

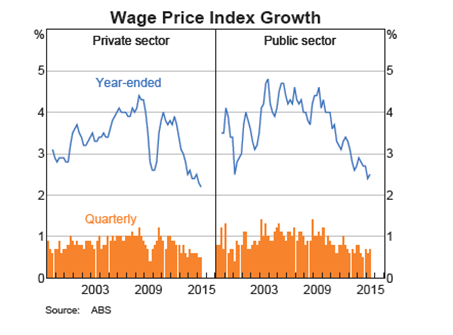

On top of currency devaluation, Australian capitalists have used rising unemployment and union inertia to attack wages. Average weekly earnings have not risen for two years, while unit labour costs (which adjusts for productivity) are falling. With the union movement showing no signs of mounting a wages offensive to reverse this trend – industrial disputes accounted for only two working days lost for every 1,000 employees in the March quarter of this year - Australian capitalists can enjoy the international cost advantage of a cheaper currency without seeing it eaten away by wage hikes (Figure 4).

SOURCE: RBA, The Australian economy and financial markets chart pack, September 2015

The problem with low wages, however, is that it discourages Australian companies from investing in more capital-intensive processes which are the source of long term productivity growth.

The ‘reform agenda’

Projections of slow productivity growth, along with a falling labour participation rate as the population ages, put a ceiling on future growth. A sustained period of low commodity prices suggests that national income will be depressed for years to come, in contrast to the strong growth experienced during the mining boom. The international situation dominated by deleveraging, deflation and uncertainty in China is challenging. The task ahead of the Australian capitalist class is how to win support for a new round of ‘reform’ to deal with this less favourable climate. As the Commonwealth Bank put it in September:

“Looking ahead it is clear that Australia’s external environment, namely commodity prices and trading partner growth, will present changes over coming years. It means there is an ongoing need for domestic reforms. Lifting national incomes will require some consistent economic reforms aimed at lifting national productivity and enhancing competitiveness.”

The Bank identified these reforms as concerning “tax politics and the operation of goods, services and labour markets”. The most important that have been canvassed in the media, the Productivity Commission and by cabinet ministers include: widening the GST by eliminating the exemptions and increasing the GST rate to 15 percent; reducing the corporate tax rate and marginal income tax on high income earners, possibly with the political sweetener of reduced tax concessions on superannuation and capital gains; providing more opportunities for private providers by outsourcing health and education services; increased public spending and public-private partnerships to build infrastructure needed by business; improving workforce skills; reforming media ownership laws to allow greater monopolisation of the industry; and reintroducing statutory individual contracts, weakening minimum wage provisions, reducing union rights and cutting penalty rates.

With Malcolm Turnbull as prime minister, the capitalists are now more confident than for years that some of these reforms may be forthcoming, if not in this term of government, at least in the next. We can expect a continuing propaganda offensive for this agenda by the government, the Reserve Bank, the BCA, the IMF and the Grattan Institute.

For the time being, there appears to be little appetite for draconian budget cuts given the weakened state of the domestic economy. Business is worried that cuts to government spending will smash business and consumer confidence and flatten economic activity.

On the other hand, Treasury, the international credit agencies and organisations like the IMF and OECD want to see some measures taken to reduce the rate of growth of public debt. Scott Morrison’s comment in his first major press conference as Treasurer that Australia has ‘a spending problem, not a revenue problem’ is an indication that cuts are still on the table. So too is newly appointed Treasury secretary John Fraser’s professed enthusiasm for austerity budgets.

Even if the Liberals are defeated at the next federal election, business might confidently expect that the ALP will meet many of its demands, given the party’s policy of reducing corporate tax rates to 25 percent and its record in office under Rudd and Gillard. The ACTU’s feeble response to the push for a cut to corporate tax in September and its uncritical attitude to Shorten’s right wing economic agenda suggests, further, that Labor in government would not experience much opposition from the unions.

Summary

1. The coming together of three factors – the end of the mining investment boom, a big boost to commodity supplies on world markets and the slowdown in the Chinese economy – constitutes a significant shock to the Australian economy by reducing an important source of aggregate demand, sharply lowering the terms of trade and cutting national income as commodity prices sink.

2. A mini property boom, by stoking consumer spending and new construction, has eased some of the problems associated with the end of the mining investment boom.

3. Nonetheless, the stimulus from the property boom has not been enough to offset the decline in investment in other sectors. The result is downward pressure on economic growth.

4. Trend rates of economic growth and productivity growth have been falling for a sustained period. With national income now also declining, these are pressing problems faced by Australian capitalism.

5. Lower growth hurts the Australian economy in relation to unemployment, the budgetary position and net migration and thus population growth.

6. Important vulnerabilities in the Australian economy also include:

- the potential for a reversal of the property boom, with flow-on effects to the banks and household spending; and

- dependence on a narrow range of exports in which it is a price taker on world markets.

7. The international situation is characterised by:

- stock market volatility;

- the slowdown of China and associated capital outflow from China and the emerging market economies, putting upward pressure on interest rates;

- sluggish growth at best in the advanced economies;

- a strong US dollar, causing additional pressure on world trade; and

- deleveraging in financial markets which pose the threat of deflation in the world economy.

8. The Australian capitalist class does have two factors going in its favour: a more competitive currency and stagnant real wages (and an inert trade union movement) which can help it adjust to the more turbulent economic environment.

9. The accession of Turnbull as Liberal prime minister gives the ruling class another opportunity to pursue its agenda of ‘economic reform’. The ALP federal leadership will be no threat to this agenda.