The 40th anniversary of the Kerr coup has provoked considerable media coverage but predictably fails to highlight the scale of the tumultuous social upheaval that engulfed Australia.

Mick Armstrong, one of those who took to the streets in November 1975, draws out some of the lessons of one of Australia’s greatest working class struggles.

----------

The Kerr coup that overthrew the Whitlam government proved two things. First, that any attempt to achieve major social reform through parliament is doomed to failure.

Second, that enormous social upheavals in which the masses fight for power don’t occur only in poverty-stricken underdeveloped countries, but are possible in advanced capitalist countries such as Australia.

Tremendous euphoria surrounded the election of the Whitlam government in December 1972. After 23 years of stultifying conservative rule, it seemed that massive social change was on the agenda.

In the late ’60s, an upsurge of strikes for improved wages and conditions intersected with a radicalisation of young people centred on opposition to the Vietnam War. But while millions of Labor supporters hoped for a new era of reform, Whitlam was no radical. He had ridden to power by crushing the ALP left.

The ruling class – including the Murdoch press, which backed Whitlam in 1972 – hoped that Labor, by introducing some limited reforms to “modernise” capitalism, would tame working class militancy. But while Whitlam was able to coopt sections of the protest movements, Labor was less successful in heading off working class demands.

In 1974, strike action surged to a postwar record as workers fought for a decent share of the boom. Then, in late 1974, Australia was engulfed by a worldwide economic recession. The bosses decreed that reforms were totally off the agenda and that living standards had to be cut to maintain corporate profits. Whitlam tried to oblige them.

He dumped more left wing ministers like Jim Cairns and Clyde Cameron and appointed a new treasurer, Bill Hayden, who introduced an austerity budget in 1975 that slashed education and social services. Wages were pegged.

But the bosses were not satisfied. They thought that Liberal leader Malcolm Fraser would be capable of really putting the boot into workers, who had been forced onto the defensive by rising unemployment and demoralised by Labor’s betrayals.

With their born-to-rule arrogance, the Liberals and their big business backers turned to the governor general, the arch-reactionary John Kerr, to overthrow the government. But they badly – almost fatally – miscalculated.

The Kerr coup was the closest Australia has come to a revolutionary upheaval since the end of World War Two. Millions of workers began to see that all our rulers’ talk of democracy was a fraud. They saw that real power resided in the boardrooms, not in parliament, and that the only way that we could have a say was on the streets and through strike action to hit the bosses’ profits.

The response to the coup was dramatic. Within hours, metalworkers, wharfies, public servants and building workers – you name it – walked off the job all around the country. Spontaneous demonstrations took over the streets.

Mass strikes continued in the following week. On 14 November, half a million workers stopped work in Melbourne and another 100,000 in Queensland.

There were enormous militant demonstrations. The Liberal Party headquarters in Melbourne was stoned, and there was a mass march on the Stock Exchange.

For a time, it looked like the bosses would have to back down. Militant workers were demanding a general strike.

But then the old reliables, the trade union leaders and ALP politicians, moved to contain things. Bob Hawke, then the head of the ACTU, called on workers to “cool it”, and Communist Party union leaders such as John Halfpenny, who were influential among key sections of militant workers, backed him.

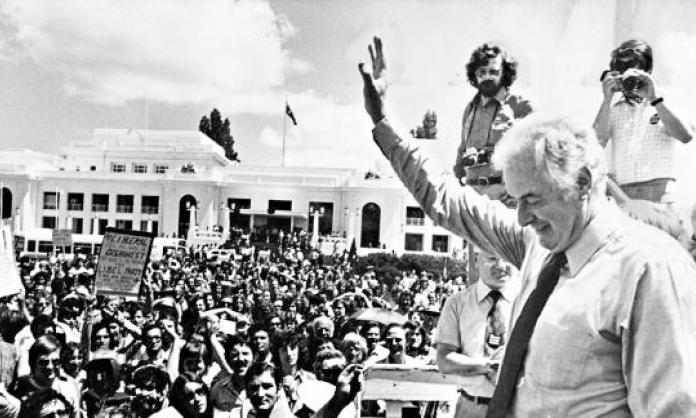

Gough Whitlam urged workers to express their rage through the ballot box, not on the streets. The bosses were let off the hook.

Once the momentum went out of the strikes and demonstrations, the press barons went back on the offensive. Some workers became demoralised. And Fraser triumphed at the polls.

Nevertheless, the Kerr coup showed the power of workers to intimidate the bosses.

When the news of Whitlam’s sacking came through, there was rejoicing on the floors of stock exchanges all around Australia. Share prices rocketed. But within a few days – after witnessing the outbursts of militancy on the streets and the wave of strikes sweeping the country – the bosses were singing a very different tune.

An editorial in Murdoch’s Australian reflected their fears. It stated that the demonstrations were “ominous” and raised “the very real danger that people might seek to express their opinions violently rather than democratically through the ballot box”.

Murdoch’s worst fears were confirmed the following day, when demonstrators besieged his Sydney headquarters to prevent his papers coming out and burnt them in the streets.

The bosses prepared for the worst. The army was put on alert and prepared for use against workers, just in case the Labor leaders could not contain the outrage.

The Kerr coup didn’t in the end provoke a revolution. This was partly because the revolutionary left was not strong enough to challenge the ALP and union leaders who wanted to “cool it”.

But it was also the case that most workers did not see the need to go beyond fighting to restore Whitlam to office. They did not see the need to settle accounts with capitalism itself.

The worldwide economic crisis had only just hit Australia. Most workers saw the recession of 1974-75 as only a temporary blip in an ongoing boom.

Today it is clear that the stagnation of the world economy is permanent. All around the Western world, the giant corporations and their governments are forced, year in and year out, to attack working class living standards to maintain their profits.

In Greece at the start of this year, workers responded by electing a left wing Syriza government committed to opposing austerity. But just as in Australia in 1975, the capitalists of Greece and across Europe had no respect for democratic mandates.

They were absolutely determined that there should be no retreat from austerity and were prepared to go to any lengths to achieve that aim. In the face of this pressure, Alexis Tsipras’ Syriza government abjectly capitulated, but if he had not done so, there was always the Kerr coup-style option.

The bottom line is that the bosses have absolutely no commitment to genuine democracy. They will abide by the rules of the parliamentary game only when it very much suits their interests.

When their profits are threatened, they have no hesitation about tearing up the rule book. Our side has to learn to fight fire with fire.